|

Ley-lines:

('Ley','lea' - 'A clearing') Ley-lines:

('Ley','lea' - 'A clearing')

('Heilige

Linien' to the Germans 'Fairy

paths' to the Irish, 'Dragon Lines' to the Chinese, 'Spirit Lines' to

Peruvians and 'Song Paths'

to the Australian Aborigines - and so on around the world).

Most cultures have traditions and words to describe the

straight, often geometric alignments that ran across ancient landscapes, connecting

both natural and sacred prehistoric structures together. Usually the names given to represent these invisible lines are translated to an equivalent of 'spirit', 'dream', or

'energy' paths. However, apart from the physical presence of the sites

themselves, proving the presence of a 'connection' between them is

something that researchers have found notoriously elusive.

Amongst the widely

differing (and often simplistic) theories that attempt to explain why

ley-lines and landscape alignments first appeared, the following theories

probably say as much about us now as at any time in the past, yet we are bound to

acknowledge and respect the following writers opinions and conclusions as 'they', the following

few, are the giants upon whose shoulders this field of study current sits:

|

The

Definition of a Ley-line: |

Even though the term 'Ley-line was originally conceived

by Alfred 'Watkins, by 1929, he had discarded the use of the

name 'ley' and referred to his alignments only as 'old

straight tracks' or 'archaic tracks'

"It is quite useless looking

for existing fragments, however old, of roads which may remain

from the first track, although, as we shall see, some bits may

form useful indications of its site. The changes from early

days have been so many in the matter of roads. We must

therefore clear our minds, not only of what we think of roads,

even Roman ones, but of our surmises, and begin again." -

Alfred Watkins (4)

'Ley lines

are hypothetical alignments of a number of places of

geographical interest, such as ancient monuments and

megaliths. Their existence was suggested in 1921 by the

amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins, whose book 'The Old

Straight Track' brought the alignments to the attention of

the wider public'.

This explanation by no means completes the

modern definition of a ley-line, as we cannot say for example that all alignments of

stones are ley-lines, however old they are. Nor

does it follow that all ancient sites were aligned

deliberately, even those that appear to have been.

Alfred Watkins, the modern

founding father on the subject, created the first basic set of

guidelines in order to describe ley-lines according to his

perception. As we have learned more about ley lines, so we have had

to adapt these original guidelines in order to explain our

findings, whilst keeping to the context with Watkins' original

ideas.

The following natural and man-made

features were suggested by Watkins to be reliable ley-markers:

Mounds, Long-barrows, Cairns,

Cursus, Dolmens, Standing stones, mark-stones, Stone circles,

Henges, Water-markers (moats, ponds, springs, fords, wells),

Castle, Beacon-hills, Churches, Cross-roads, Notches in hills,

Camps (Hill-forts),

Any true Watkinsian ley requires

it to have a start (or finish) point in the shape of a hill.

(4)

From map and fieldwork,

Paul Deveraux concluded

that all Henges

are likely to indicate the presence of a Ley.

(2)

We can

therefore begin to gauge the strength of a ley-line according to its length, accuracy of deviation, number

of ley-markers and their individual significance. We can also

separate ley lines into basic categories such as astronomical,

funerary, geometric etc, as the following examples illustrate:

(Return

to the top)

|

What

was the Original Purpose(s) of Ley-lines? |

There are several developed theories on the

purpose of ley-lines,

many of which offer valid potential; something which in itself illustrates the complexity

of unravelling the myriad of alignments from several millennia of activity.

It is likely that ley-lines are

a product of different elements from several of the following theories, being

created at different times, for different purposes. The following examples are

the current contenders for explaining how such a dedication to straight-lines

has led mankind its present position.

It is important to recognise

the distinction between ley-lines and geometric alignments.

Although there is little

direct evidence for 'religious' worship in the modern sense of the word at megalithic sites, there is certainly evidence that

funerary rites were involved at several important locations (some of which may

be classed a secondary use). The burial of

valuable goods alongside funerary remains, placing of remains inside stone

chambers underground, and alignment of funerary structures or their inhabitants

with the rising sun, all attest to the fact that funerary ley-markers were not

placed according to

purely 'scientific' criteria, although they may also have been added to existing

pre-existing ley-lines.

A number of rituals and traditions have been associated with the path taken by

funerary parties. Traditionally known as 'death roads' (dood-wegen or geister-wege).

The fact that 'spirit paths' are traditionally straight and seem to include the

same 'markers' as ley lines significantly increases the argument for some of the

leys having once served this function. Spirit lines are also invisible, and are

viewed as 'tracks' or 'paths' for the movement of the spirits, which may explain

why markers are often not visible from one location to another (an argument traditionally

used against the existence of leys themselves).

Funerary Traditions:

Watkins mentions the English funerary tradition of stopping at a

crossroads and saying a prayer, a custom still practiced to this day. Other

customs involve walking around or 'bumping' churches and stones en-route. Processions are not

supposed to carry a corpse twice over the same bridge and custom forbade singing

or music on a bridge Another interesting funerary-custom, still practiced

into the 20th century was for mourners to carry a pebble and when they passed

certain spots, throw

their pebbles into a pile of previous mourners pebbles.

The 'Fairy paths' of

the Irish also have folklore associated with them. There are numerous stories of

houses being built over Fairy-lines and being then being destroyed or cursed.

Stones, crosses, crossroads, bridges and Churches are all the same points on

Watkins list of ley-markers, although it is probable that many of the alignments that involve churches and

cemeteries, or which pass areas with traditional funerary rites or death rituals

have been mistakenly classified as 'ley lines' as funerary paths are not

necessarily always straight.

Many important ley-markers are associated with springs and water

sources.

The Chinese art

of 'Feng-shui', or 'wind and water', also means 'that which cannot be seen and

cannot be grasped'. The duty of the practitioners of the art was to determine

the flow of 'lung-mei', or 'Dragon currents'. Every building, stone and planted

tree was so placed into the landscape as to conform to the 'dragon currents'

which flowed along these lines. The main paths of the forces were believed to be

determined by the routes of the sun, moon and five major planets. We know that the

Earth is encompassed within a magnetic field. The strength and direction of the

magnetic currents vary according to the position of the sun, moon and closer

planets. The magnetic field is also affected.

It is possible that this

field may have been

detected (i.e. through dowsing),

and mapped out in the past. Noobergen

(6), reminds us that the earths natural

magnetism was believed to have been used to re-fertilise the soil, in the same

way as the

aborigines did with their 'turingas' or 'dream lines'. He also mentions that

there is scientific research that shows that water is extremely sensitive to electromagnetic

fields, and that as the fields are changed or influenced, so the chemistry of

the water may be altered too. Horticulturalists have discovered that plants

placed within a magnetic field grow more than six times faster than in normal

conditions. We are able to show today that the strength and direction of the

Earths magnetic currents vary according to the positions of the Sun, Moon and

other planets.

The fact it took so long for us to realise that astronomy was

in any way involved with megalithic culture is almost as surprising as the

fact that it was ever forgotten. Although there

has been a traditional resistance to this theory from the scientific

establishment, we live in a time when it is finally accepted that many of the

larger megalithic constructions were designed so as to be able to accurately

identify celestial objects or measure their cycles.

The clear link between megaliths and astronomy can also be

said for megaliths and ley-lines, as they are often found to be prime ley-markers,

and intersections of several ley-lines (i.e.,

Arbor-Low,

Avebury,

Stonehenge

etc).

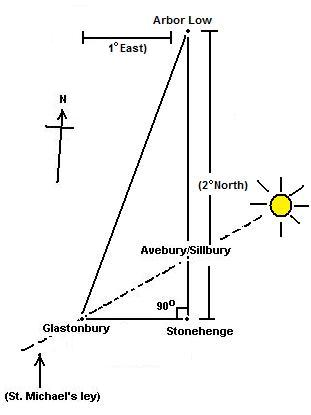

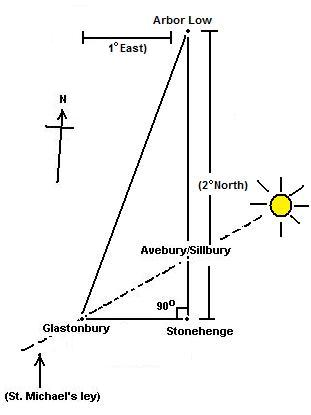

One of the largest Leys in England, the

so-called St. Michaels Ley, is aligned along the

path of the sun on the 8th of May (The spring festival of St.

Michael) and can therefore be considered

astronomical. This line passes through several megalithic sites before it

reaches Glastonbury,

(artificially shaped to follow the direction of the ley), and then on to the

Avebury/Silbury complex, both significant English landscape features.

The St. Michael's Leyline

follows the path of the Sun on the 8th May (The spring festival of

St. Michael).

(More

about St. Michael)

The

St. Michael's ley has been shown to be inter-related with several

other prominent British megaliths through geometry, astronomy and an

apparent knowledge of longitude/latitude, not least of all to

Stonehenge. Stonehenge,

whilst not being a part of the St. Michael ley, is connected with both

Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury through geometry, and also forms the crossing point

of several prominent ley-lines - both astronomical and non-astronomical. The first astronomically significant ley-line

to pass through Stonehenge was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer, and later

extended to 22 miles in length by K. Koop. This ley follows the path of the

mid-summer sunrise on a bearing of 49� 15'. (2) The

St. Michael's ley has been shown to be inter-related with several

other prominent British megaliths through geometry, astronomy and an

apparent knowledge of longitude/latitude, not least of all to

Stonehenge. Stonehenge,

whilst not being a part of the St. Michael ley, is connected with both

Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury through geometry, and also forms the crossing point

of several prominent ley-lines - both astronomical and non-astronomical. The first astronomically significant ley-line

to pass through Stonehenge was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer, and later

extended to 22 miles in length by K. Koop. This ley follows the path of the

mid-summer sunrise on a bearing of 49� 15'. (2)

Another significant ley-line to pass through Stonehenge was

also identified by Lockyer, and can be shown

to extend accurately for 18.5 miles. It skirts only the edge of the henge at the

junction of the avenue, missing the centre (and the sarsen stones) altogether.

This line runs on a bearing of 170� 45', and appears to have no astronomical significance.

The alignments at S tonehenge

therefore appear to offer a fusion of

funerary, astronomical and geometric practices, simultaneously connecting three of the most significant

locations in southern England. Glastonbury, Stonehenge and Avebury/Silbury, which

all align

to create a perfect right-angled triangle, accurate to within 1/1000th part. It

is from this historic starting point that we can begin unravelling the complexity of prehistoric geometry of the British

landscape.

(More about Archaeoastronomy)

:

The previous

examples have offered a indication that geometry might be involved in the

orientation of some ley-lines. It is arguable that as many of the sites are aligned astronomically, and as

geometry is a natural product of astronomy, the effect might be a product of

'automatic' or 'accidental' geometry within the layout of certain sites,

but this does not explain geometry between sites which certainly involves

surveying techniques, which in turn requires deliberate and applied mathematics

(logarithms and trigonometry or their equivalent).

Sir Norman Lockyer

(Astronomer-Royal), was the first 'respectable' person to recognize

geometry in the ancient English landscape. He

noticed

the geometric alignment between

Stonehenge, Grovely (Grove-ley)

castle and Old Sarum (The site where the original Salisbury

'cathedral was built). The three form an equilateral triangle

with sides 6 miles long, with the Stonehenge-Old Sarum

line continuing another 6 miles to the site of the present Salisbury Cathedral,

and beyond.

This extremely

significant finding shows both that the early megalithic builders were aware of

both astronomy and geometry, and combined them deliberately into their

constructions. At the same time as this reasonable astonishing revelation, we

are able to see how many ley-markers may have been introduced along pre-existing

alignments, and it is important to know the origin of all the markers on

ley in order to accurately determine its origin and purpose.

The

megalithic tradition in the British Isles can apparently be traced back to at

least 3,000 B.C., if not earlier still. This tradition seems to have been based

on a very sophisticated philosophy of sacred science such as was taught

centuries later by the Pythagorean school. As

Professor Alexander Thom observes in his book Megalithic Sites in Britain

(1967): �It is remarkable that one thousand years before the earliest

mathematicians of classical Greece, people in these islands not only had a

practical knowledge of geometry and were capable of setting out elaborate

geometrical designs but could also set out ellipses based on the Pythagorean

triangles.�

(More about

Geometric Alignments)

The Aborigines

of Australia tell of a 'pastage', which they call the 'dream-time', when

the 'creative

gods'

traversed the country and reshaped the land to conform with important paths

called 'turingas'. They say that at certain times of the year these 'turingas'

are revitalised by energies flowing through them

fertilising the adjacent countryside. They

also say that these lines can be used to receive messages over great distances.

The Incas used 'Spirit-lines' or 'ceques'

with the Inca temple of the sun in Cuzco as their

hub. (9)

The Jesuit father Bernabe Cobo referred to these 'ceques'

in his 'History of the new World'. 1653. These were lines on which 'wak'as'

were placed and which were venerated by the local people. Ceques were described

as sacred pathways. The old Indian word 'ceqque' or 'ceque' means boundary or

line. Cobo describes how these lines are not the same as those at Nazca, being

only apparent in the alignment of the wak'as. These wak'as were most often

in the form of stones, springs, and often terminating near the summits of holy

mountains. Documentary records made by the Spanish record that 'qhapaq Hucha'

ceremonies of human sacrifice (usually children), took place at wak'as as an

annual event and also at times of disaster. In the 17th century the Roman

catholic church ordered that the holy shrines along the routes be destroyed. As

in Europe, many ancient holy places were built over with churches.

Elsewhere in

America, fragments of ancient tracks can still be found such as the Mayan

'Sache', of which 16 have so far been found originating in Coba,

Mexico. The following is a description of one found

in the Yucatan;

'...a great

causeway, 32ft wide, elevated from 2-8 ft above the ground, constructed of

blocks of stone. It ran as far as we could follow it straight as an arrow, and

almost flat as a rule. The guide told us that it extended 50 miles direct to

Chichen itza (it started from the other

chief town of Coba) and that it ended at the great mound, 2km to the north of

Nohku or the main temple in a great ruined building'.

(3)

Other ancient

tracks have been found in New Mexico. These roads are barely visible at ground

level and radiate from

Chaco Canyon.

As in Bolivia, some of these paths run parallel and others lead to nowhere. One

of the major sites connected by the 'Anasazi' roads is Pueblo Alto.

The German equivalent of ley lines is 'Heilige

Linien', or 'holy lines'. The area of 'Teutberger Wald', also known as the

'German heartland' has a significant network of these lines which include the

Externsteine and the megalithic stone circle at Bad Meinberg.

It has been suggested that there are enough

prehistoric sites to play statistical 'dot to dot' with, and that a survey of

English pubs and telephone boxes will yield the same level of statistical

probability as determined by ley-hunters. This is a reasonable point and

therefore needs to be remembered at all times. The argument of random chance is

countered by the addition of folk-lore and tradition associated to ley-markers

and through exhaustive research that has enabled predictions of locations of

ancient tracks and ley-markers to have been later substantiated through

archaeology. (4)

(Return

to the top)

|

When were Ley-lines

First Made.

|

Exactly how old the original straight paths were is a matter of

debate. We can read of ley-lines connecting offshore beneath the English channel

(1), upon which basis, Behrand concluded that these particular leys must have

been marked out between 7,000 BC and 6,000 BC.

We know that the European landscape was

significantly redesigned using geometric principles in the middle ages by the

Cathars, Knights Templar and the Holy church of Rome. We also know

that a large number of the great Cathedrals Churches and Holy sites were built over

earlier pre-existing pagan sites and constructions (Xewkija,

Knowlton,

Rudstone

etc) The re-use of ancient sites can even be seen to extend back to

pre-historic times such as the re-use of several large menhirs as capstones for

passage-mounds in the Carnac region. It is this

simple fact, combined with the observation that these same megalithic structures

are invariably found to be the ley-points along which such lines are determined,

that places the origin of ley-lines into the prehistoric past. (It by no means

follows that all megalithic sites were placed on ley-lines).

It is not uncommon to find the terms

'ley-lines' and 'roman roads' in the same context, but it is important to draw a

distinction between the two, as there is absolutely no pre-requisite for a

ley-line to include roads, pathways, or any visible connection between

ley-points of any kind whatsoever. It is the case however, that some ley-lines

have been identified along which ancient paths or roads follow (or run

alongside), and it is perhaps worth first considering the origin of these

ancient tracks, and their connection with ley-lines.

In the first place, many of the long

straight roads of Britain have been classified incorrectly as 'Roman Roads'. A

fact that can be proven through their existence in Ireland, as noted by J. Michell,

who pointed out that '...these same roads exist in Ireland, a

country which never suffered Roman occupation..', then also noted the fact

that '...beneath the Roman surfaces of the Fosse Way, Ermine Street and

Watling Street excavators have uncovered the paving stones of earlier roads,

at least as well drained and levelled as those which succeeded them'.

The same observation was made in other parts

of Europe by the Romans themselves, who

in their conquest of the Etruscans,

noted standing stones set in linear patterns over the entire countryside of

Tuscany. Romans also record discovering these 'straight tracks' in almost every

country they subjugated: across Europe, North Africa, Crete, and the regions of

ancient Babylon and Nineveh. Fairly conclusive then - the roads existed

before the Romans. In fact, considering the scale of development in the

Neolithic period approx 5,000 - 3,000 B.C. it is quite likely that they (or the

first, or some at least), existed at that time too, if only to connect sites.

|

A Chronology

of European Geomancers. |

In

1740, Dr.

William Stuckley,

first noted that the axis of Stonehenge and the Avenue leading from it point

to the north-east, 'whereabouts the sun rises when the days are longest'.

He perceived the whole British landscape as laid out according to a sacred

'druidic' pattern, and etched with symbols of serpents and winged discs. At

Barrow near Hull he found a great earthwork representing a winged circle,

its trenches arranged so as to measure the seasonal tides of the Humber

Estuary. He disclosed another near Navestock Common in Essex which now lies

forgotten in a small wood, near the northern most Central-Line terminal. In

his book on Avebury, Stuckley wrote:

'...They have made plains

and hills, valleys, springs and rivers contribute to form a temple three

miles in length...They have stamped a whole country with the impress of this

sacred character'.

William Black

-

In the 1800's, an expert

on roman roads announced his theory that he had uncovered a whole system of 'grand

geometric lines', radial and polygonal, which ran across Britain and beyond.

He pursued his studies for fifty years before releasing the theory. They linked

major landmarks in a precise manner, even defining the boundary markers of

counties. Black died in 1872. (4)

Sir Montague Sharp

-

Working in the early years of the 20th century, he discovered a network of

rectangles in Middlesex and became aware that ancient churches, which he

recognised as marking pagan sites, fell on alignments.

(2)

In

1904,

F. J. Bennet

-

Published the findings on what he called the 'Meridianal lines'

in Wiltshire and Kent, which apparently linked prehistoric sites and ancient

churches in generally N-S alignments, often with regular divisions, based on the

mile, between sites.

(2)

In

1911,

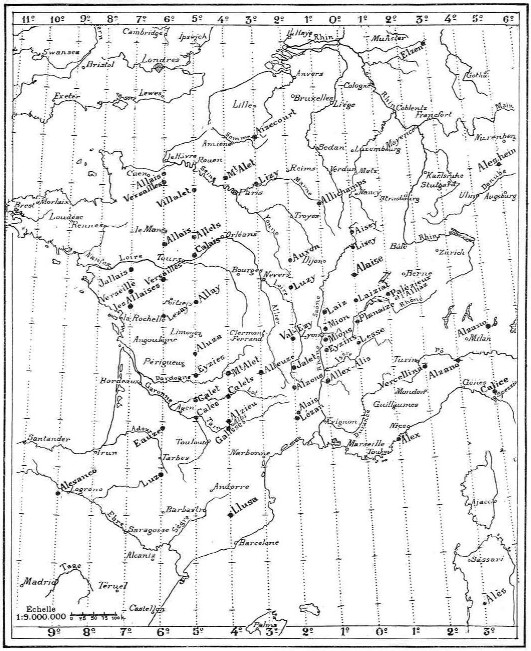

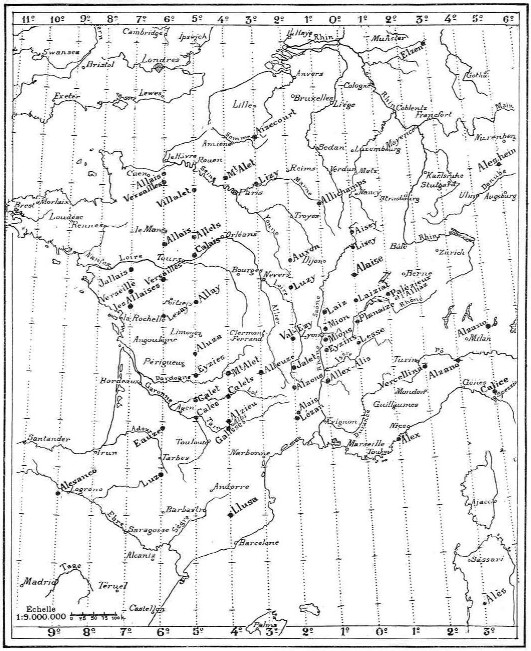

Xavier Guichard

- The French philologist started

researching the origins of ancient European place-names. He came to the

conclusion that there were three basic root names: Burgus, Antium

and

Alesia, of which the last was unique as never having been given to a

town or village founded in historic times. In its Greek form of

Eleusis, the word dated from the legendary pre-Homeric times; in its

Indo-European roots, Ales,

Alis or Alles meant a meeting point to which people travelled. His

research explored derivatives of the word 'Alesia' as far afield as

Egypt (Eleusis on the Nile Delta) and Poland (Kalisz), with the highest

concentration in France. Guichards' research into the people who first

used the word and its true origin and meaning consumed the next 25 years

of his life. He identified two invariably identifying features in

connection with associated sites: 'landscaped hills overlooking rivers,

and man-made wells of salt or mineral water' . He deduced that the name

was associated with 'travel stops' where one could be sure of receiving

these life-giving properties. His final results revealed over 400 sites

in France alone, which appear to have been placed in a geodetic system

extending across Europe, and centred on a remote ancient site called

Alaise, near Besancon in southern France. He suggested that Europe had

been divided into two 'roses-des-vents' (compass cards such as

those used by Greek geographers): one of 24 lines that divided the

horizon into equal segments; and one of four lines that marked the

meridian and the equinox, and the solstices. This implied, he said, a

knowledge of latitude and longitude, and the position of the North Pole

and the Equator. Moreover he was able to trace a common distance between

sites that suggested a common unit of measurement. Referring

to several old cities in his native France says, �These

cities were established in very ancient times according to their

immutable astronomical lines, determined first in the sky, then

transferred to the Earth at regular intervals, each equal to a 360th

part of the globe".

In 1936, and without any apparent knowledge of Alfred Watkins work on

'ley-lines', or his similar conclusions over associations with water and

salt, Xavier Guichard had a book printed at his own expense called

Eleusis Alesia (complete with 555 maps). Unfortunately, his home at

Abbeville was bombed during the second world war, killing him and

destroying almost all copies of his book. In

1911,

Xavier Guichard

- The French philologist started

researching the origins of ancient European place-names. He came to the

conclusion that there were three basic root names: Burgus, Antium

and

Alesia, of which the last was unique as never having been given to a

town or village founded in historic times. In its Greek form of

Eleusis, the word dated from the legendary pre-Homeric times; in its

Indo-European roots, Ales,

Alis or Alles meant a meeting point to which people travelled. His

research explored derivatives of the word 'Alesia' as far afield as

Egypt (Eleusis on the Nile Delta) and Poland (Kalisz), with the highest

concentration in France. Guichards' research into the people who first

used the word and its true origin and meaning consumed the next 25 years

of his life. He identified two invariably identifying features in

connection with associated sites: 'landscaped hills overlooking rivers,

and man-made wells of salt or mineral water' . He deduced that the name

was associated with 'travel stops' where one could be sure of receiving

these life-giving properties. His final results revealed over 400 sites

in France alone, which appear to have been placed in a geodetic system

extending across Europe, and centred on a remote ancient site called

Alaise, near Besancon in southern France. He suggested that Europe had

been divided into two 'roses-des-vents' (compass cards such as

those used by Greek geographers): one of 24 lines that divided the

horizon into equal segments; and one of four lines that marked the

meridian and the equinox, and the solstices. This implied, he said, a

knowledge of latitude and longitude, and the position of the North Pole

and the Equator. Moreover he was able to trace a common distance between

sites that suggested a common unit of measurement. Referring

to several old cities in his native France says, �These

cities were established in very ancient times according to their

immutable astronomical lines, determined first in the sky, then

transferred to the Earth at regular intervals, each equal to a 360th

part of the globe".

In 1936, and without any apparent knowledge of Alfred Watkins work on

'ley-lines', or his similar conclusions over associations with water and

salt, Xavier Guichard had a book printed at his own expense called

Eleusis Alesia (complete with 555 maps). Unfortunately, his home at

Abbeville was bombed during the second world war, killing him and

destroying almost all copies of his book.

(More about

Xavier Guichard)

In 1911,

W.Y.Evans-Wentz,

mentions the 'Fairy paths', along which invisible elemental spirits are believed

to travel across Ireland. In his book 'The fairy faith in Celtic countries', he

referred to them as the 'arteries' through which the Earth's magnetism

circulates.

After the 1914-18 world

war,

Major F.A. Menzies,

M.C., a distinguished British army engineer

and surveyor, decided to live in France where he chose to investigate the

energies of the earth. Major Menzies was very interested in the study of

radiesthesia and while in France he was tutored by M. Bovis and other leading

French exponents of radiesthesia. During this time Major Menzies became aware of

the importance of the Feng Shui system of geomancy which had been developed by

the ancient Chinese geomancers. He was able to see examples of the Chinese

geomancers compass in certain museums in Paris, which had been brought from

China by Jesuit missionaries. Major Menzies made drawings of one of these

amazing compasses and eventually constructed a modified version for his own use.

By learning how to use the Chinese geomancers compass in conjunction with his

British army compass, Major Menzies became very proficient in locating earth

energy alignments (ley-lines), and also sources of noxious energy which were

creating areas of geopathic stress and ill health. Eventually, Major Menzies

returned to England where, during the 1940's, he carried out research work,

using both his compasses, at the ancient megalithic site of

Stanton Drew, six

miles south of Bristol in the south west of England. Stanton Drew is comprised

of several megalithic stone circles which are said to possibly date back to

3,000 B.C. They show several astronomical alignments and are believed to have

been associated with solar (fire) worship in Pagan times. While investigating

these stone circles, Major Menzies had an extraordinary experience which he

subsequently related to a friend and fellow surveyor, George Sandwith. Major

Menzies said:

�Although the

weather was dull there was no sign of a storm. Just at a moment when I was

re-checking a bearing on one of the stones in that group, it was as if a

powerful flash of lightning hit the stone, so the whole group was flood-lit,

making them glow like molten gold in a furnace. Rooted to the spot - unable to

move - I became profoundly awestruck, as dazzling radiations from above, caused

the whole group of stones to pulsate with energy in a way that was terrifying.

Before my eyes, it seemed the stones were enveloped in a moving pillar of fire -

radiating light without heat - writhing upwards towards the heavens: on the

other hand it was descending in a vivid spiral effect of various shades of

colour - earthward. In fact the moving, flaring lights gyrating around the

stones had joined the heavens with the earth"

Major Menzies' experience

at Stanton Drew may have a direct bearing on the �fire-pillars� of ancient

Phoenician tradition and elsewhere. To re-quote Rev. J.A. Wylie: �Altein is a

name given to certain stones or rocks found in many districts of Scotland, and

which are remarkable for their great size, and the reverence in which they are

held by the populace, from the tradition that they played an important part in

the mysteries transacted in former days. Altein is a compound word -

al, a stone, and teine, fire, and so it signifies 'the stone of

fire'�.These 'stones of fire' form a connecting link between the early Caledonia

and the ancient Phoenicia�.The fire-pillars that blazed at the foot of Lebanon

burned in honour of the same gods as those that lighted up the straths of

Caledonia. Ezekiel speaks of the 'stones of fire' of Tyre, and his description

enables us to trace the same ceremonies at the Phoenician alteins as we

find enacted at the Scottish ones.� (History of the Scottish Nation,

1886, vol. I).

In 1919,

Bishop Brown,

studied the cup and ring markings of the 'recumbent' stones of Scotland. He

found that many of them were accurately arranged to form patterns of various

constellations, but in each case the image was reversed. Watkins believed that

the markings indicated the paths of leys. Perhaps the two are compatible.

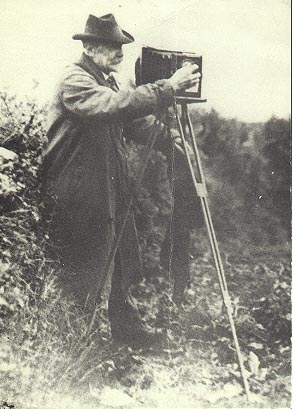

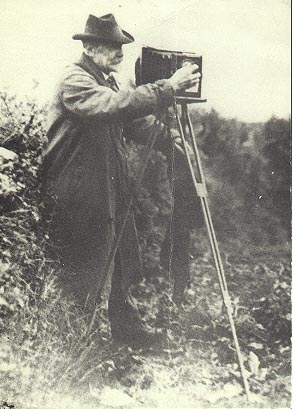

Alfred

Watkins

first became aware of the alignment of ancient British sites in

the early 1920's, in what he

described as:- '...a flood of ancestral memory...'. Alfred

Watkins

first became aware of the alignment of ancient British sites in

the early 1920's, in what he

described as:- '...a flood of ancestral memory...'.

He concluded that a feature of

the old alignments was that certain names appeared with a high frequency along

their routes. Names with Red, White and Black are common; so are Cold or

Cole, Dod, Merry and Ley.

(The last as we know, he used to name the lines, although it has been

noted that 'ley' is Saxony for 'fire'). He suggested that ancient travellers

navigated using a combination of natural and man-made markers. Certain lines

were known by those that most frequented them so that 'White' names were

used by the salt traders; 'Red' lines were used by potters, 'Black'

was linked to Iron, 'Knap' with flint chippings, and 'Tin' with

flint flakes. He also suggested that place names including the word 'Tot',

'Dod" or 'Toot' would have been acceptable sighting points so that the 'Dodman',

a country name for the snail, was a surveyor, the man who 'planned' the leys

with two measuring sticks similar to a snail's horns (or the 'Longman of

Willington')

(It is noted that the Germans have similar names such as 'Dood' or "Dud',

which mean 'Dead').

Watkins maintained that leys

ran between initial 'sighting posts'. Many of the 'mark stones', and 'ancient

tracks' he refers to have since disappeared, a situation which is considerably

unhelpful to serious research. Similarly to Guichard (above), Watkins believed

that the lines were associated with former 'Trade routes' for important

commodities such as water and salt. He found confirmation in this through

'name-associated' leys.

Even today the Bedouins of North Africa use the line system

marked out by standing stones and cairns to help them traverse the deserts.

A letter to the Observer (5 Jan 1930), notes similarities with Watkins theories

and the local natives of Ceylon, who had to travel long distances to the salt

pans. The tracks were always straight through the forest, were sighted on some

distant hill, (called 'salt-hill'), and that the way was marked at intervals by

large stones (called 'salt-stones'), similar to those in Britain.

It is

argued that if these leys were remnants of ancient tracks then

it should have once been possible to see one point from another. Also it is

noted that there are many ancient 'tracks' across Britain, such as the Ridgeway,

and none of them are dead straight.

(Lecture

by Watkins entitled: 'Early British Trackways'. 1921)

Alexander Thom

showed through vigorous research that the length of 2.72

ft was a common unit of measurement (The megalithic yard), in the geometry of

many megalithic monuments across Europe. He also found a smaller common unit of

measurement in the

spiral

carvings on certain megaliths. He concluded that the megalithic builders were

sophisticated astronomers engaged in a detailed study of the movements of

the heavenly bodies, incorporated into their structures over a long period of

observation.

( More

about the 'Megalithic Yard')

In

1929,

Joseph Heinsch,

a German Geographer,

discovered

geometric alignments

across Germany. (i.e. Xanten cathedral), Heinsch found that the mosaic

discovered in the floor was orientated towards and contained the pattern of the

layout of churches in the district. Available in English translation. (5).

In 1939.

Dr. Heinsch, read a paper to the international Congress at Amsterdam

entitled 'Principles of Prehistoric Cult-Geography'. He concluded in his

paper that the sites of the ancient 'holy centres' had been located on lines of

great geometrical figures which were themselves constructed in relation to the

positions of the heavenly bodies. Lines set at an angle of 6� north of due East

joined centres dedicated to the moon cult of the West with those of the Sun

in the East. The regular units of measurement used in this terrestrial geometry

were based on simple fractions of the Earth's proportions.

In 1929,

Wilhelm Teudt, a German evangelical

parson and contemporary of Alfred Watkins, published a book called 'Germanische

Heiligtumer', which gave details of ancient site connections called 'Helige

Linien' (Holy-Lines), that were similar to the 'leys' of Britain. His

work led to the discovery that vast areas of central Germany appear to have been

laid out so that the ancient sites are on straight lines hundreds of kilometres

long and these lines in turn form geometrical shapes. He also made a number of

associated archaeo-astronomical findings.

In 1939,

Major H. Tyler published a small

volume titled 'The Geometric arrangement of Ancient Sites' (As the

British museum copy was lost during the 'war' the book is virtually

unobtainable). J. Michell describes in 'The View over Atlantis' how Tyler

re-examined Watkins theory with the assistance of a professional surveyor. His

findings confirmed and supported Watkins original hypothesis. He also realized

that as more leys were plotted, it became evident that many of them shared a

common intersection. In some cases, concentric circles drawn from these sites

revealed other, equidistant sites. Elsewhere he found leys running parallel for

several miles (putting into question their origin as pathways). Tyler also

confirmed Watkins observation that a number of 'leys' were set to mark the

extreme positions of the Sun or Moon (referring to Dr. Heinsch paper of 1938).

An important conclusion from Tyler's research was that was that..

'...the ancient tracks did

conform to the alignments, but that they were there before the pathways were

established. The alignments were 'the remaining index of some great

geometrical arrangement of these sacred sites'.

Deveraux said of him:

....'It

seems to be getting clearer that all alignments are not connected with roads or

tracks. He felt that the only explanation of so many alignments was that they

were to do with a system of rectangular land division'.

(2)

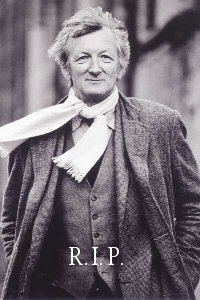

John

Michell. John

Michell.

Single-handedly re-awaked the spirit of

investigation

in the 1970's. He brought to the

public attention the existence on the famous English 'St

Michael's ley', and also revealed in

'City of revelation',

the existence of a large scale geometric

decagon across southern Britain, associating ley-lines with

both geometry and astronomy. He claimed that the ancient Celtic

'perpetual choirs' at Llantwit manor (This location is not

accurate),

Glastonbury

Abbey and

Stonehenge

were vertices of a regular decagon of majestic proportions. A

fourth vertex exists at Goring-on Thames where a major pagan

temple once stood at the junction of several important track

ways.....The

centre of the decagon is at the apparently insignificant hamlet

of

Whiteleaved Oak where the

former counties of Hereford, Gloucester and Worcester came

together. This decagon is

apparently

related by angle and distance to the

other geomantic centres of Britain. Michael Behrend supported

the concept but made two small changes to the original scheme.

Sadly, Michael left us on the 24th April, 2009.

( More

about the 'Decagon')

Livvio Stechinni

-

Stecchini believed that certain

ancient oracle centres had been intentionally separated by units of 1� of

latitude which he said was designed to create what he called an 'oracle

octave', along which the seven major centres were placed, each devoted to

one of the seven known planets, and symbolised by different sacred trees (for

more on this subject refer to the 'Tree alphabet' in R. Grave's books, 'The

White Goddess'), and it was this geometry, he believed, that formed the

basis of the 'Eleusian Mysteries'.

Note: 'Eleusis' - 'Alaise'

- 'ley' - (aisle, alley, valley)

Stecchini's theory was later included as a part of R. Temples book

'The Sirius mystery', in which he also suggested that the

distribution of oracle centres embodied an ancient knowledge

which had been stored in myth and tradition. Significantly, he

states that the pre-dynastic capital of Egypt, Behdet 'existed

before 3,200 BC', and was replaced by the city Canopus, (the

same name as the star that represents the 'rudder' of the

constellation Argo). He suggested that this was a connection

between the two mythological narratives of the �Ark� and

the �Argo�

of the Argonauts, which he said, revealed evidence of a

prehistoric system which included an understanding of astronomy

mathematics and geo-metry (as in the sense of measuring

the earth).

(More about the Eleusian Mysteries)

(More

about the World-Grid)

Paul Devereux and Nigel Pennick

- Found in

their book entitled 'Lines on the Landscape', that wherever the straight

landscape line occurred, and where it did not have any obvious function such as

a boundary or road, it appeared to have a religious significance. Their research

into ceremonies and traditions and pilgrimages associated with straight tracks

disclosed a key theme connecting them which was a belief in the dead

travelling along 'spirit/funerary paths', to the 'Otherworld'. Paul Devereux

headed the 'Dragon Project', which tried for 10 years to record and recognize

the energy that was claimed to exist at different ancient sites (specifically

the

Rollright stones), with results that

showed anomalous 'pulsing' of the outlying King Stone with ultrasonic equipment,

higher than normal Geiger readings within the circle than outside, and that the

magnetic field was significantly lower inside the circle that outside. The

Dragon project also discovered that certain stones at other circles were highly

magnetic (such as

Easter Aquorthies which has a magnetic patch

at head height). This led to research being directed to the effect of magnetic

and radioactive fields on the human brain. ('The results of the 'Dreamwork'

program were not available in 1999.

(3) It is recognised in respect of this

finding that other animal species are able to detect

magnetism

(pigeon migration). It is also recognised that the la-Venta 'Fat boy' (amongst

others), has a naturally magnetized navel and temple.

Michael Behrend

- Determined that the Stonehenge, Glastonbury Tor and Midsummer

Hill alignments form a 5:5:3 Isosceles triangle correct to 1 in 1000.

(2)

(More about Geometric

Alignments)

D. Chaundy

- Found that the White-Horse hill figures of Wessex fall into what appeared to

be ordered alignments and triangular configurations.

(2)

John Barnatt -

Undertook a survey of ancient sites of Derbyshire with a computer, and found 'Challenging

geomantic relationships' between them.

(2)

(Return to the top)

|

Examples of

European Ley-lines: |

Please

Contact-Us if you know of any interesting leylines that you think

should be on this page.

Belgian Ley-Lines:

The Weris Alignment -

Stretches over 5km across

the Belgian landscape. It includes at least 6 megaliths along its

route, and as yet no astronomical orientation has been determined.

(Quick-link)

French Ley-lines:

Mont St. Michel Ley

- The main church at Mont St. Michel is orientated at 26� north of true

east (The same as at Notre Dame). This orientation can be extended in

both directions to form an alignment with Mont Dol to the south-west,

and d'Avranches to the north-east. Mont

Dol

is the place where St. Michel is said to have fought Lucifer.

On the 8th of May (the

spring festival of St. Michael), the sun rises over d'Avranches towards

Mont St. Michel, then over Mont Dol and the huge

Dol-de-Breton.

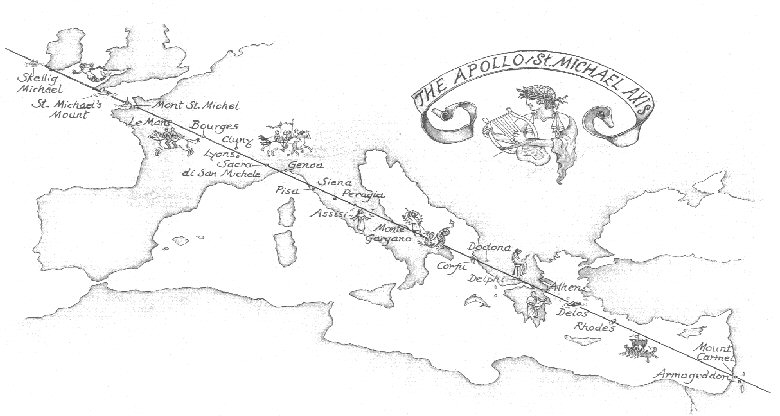

Mont St. Michel is

also associated with a larger St. Michael's line, proposed to run

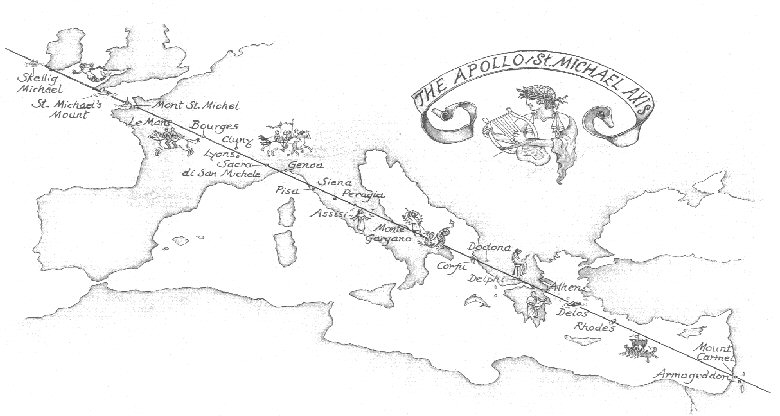

from Ireland to Jerusalem as the following map demonstrates.

The alignment is said

to extend (on a Mercatorial map), from Mount Carmel in Israel through

Delos

(dedicated to Apollo),

Delphi,

Corfu (Island of Artemis, sister of Apollo), Le Monte Gargano in Italy

(primary European sanctuary of the Archangel, and place of several

apparitions), La Sacra di San Michele in Piemont (Benedictine monastery

at 1000m), Le

Mont St. Michel of Normandie, Saint

Mickael's mount, (a peaked island surmounted by a church off the coast

of Cornwall), and Skellig Michael, an island to the south-east of

Ireland. The angle of axis is orientated SE-NW corresponding to the

zodiacal axis of virgo-pisces (7).

(More about St. Michael)

Portuguese Ley-lines:

Three of the most

significant sites in Portugal are aligned in the direction of the spring

full-moon, along an azimuth of 110�. The alignment starts near

Evora, at the

Cromeleque dos Almendres, one

of Europe's oldest stone circles, which was constructed directly under

the moons maximum southerly latitude (Stonehenge was built under the

maximum northerly setting). Approximately 3 miles further along is the

Anta Grande do Zambujeiro passage mound,

the largest of its kind in all Iberia, and orientated along the same

azimuth of 110�. This beautiful example of an astronomical (lunar)

alignment terminates significantly at the original location of the

Cromeleque da Xarez, a stone quadrangle.

(More

about the Evora alignment)

Maltese Ley-lines:

The Island of Gozo is home

to the third-largest dome in the Christian world. (Which was built over a

huge dolmen) Also on Gozo, and apparently the only large megalithic

construction on the island, is the Ggantija temple complex, from which it is

just possible to see Malta through a notch in the hills. The sanctity of

this particular location is further emphasised by the presence of the Xagra

stone circle which was constructed over a 'Hypogeum' containing the remains

of several hundred bodies.

The 'Ta Cenc' Dolmen, the

Xewxra cathedral and the Ggantija/Xagra complex were all built in alignment

across the island. The Island has an interesting geomorphic quality about

it.

(More

about the Gozo alignment)

English Ley-lines: (Map

Ref: No's) below, refer to lines on the:

English Ley-line Map.

There

are too many proposed ley-lines in Britain to show them

all. The following few are some of the better known.

St. Michael's Ley

(Map Ref: 1) -

(Astronomical).

Runs across southern England from 'Land's End' to at least Bury St.

Edmonds'. Includes Glastonbury, Avebury, Walaud's Bank and The Hurlers.

(More

about St. Michael)

Stonehenge Ley (Map

Ref: 2)

- (Astronomical).

A 22 mile ley running from

'Castle Ditches' to a series of tumuli on 'Cow Down'. (Bearing 49� 15')

(2)

(More

about Stonehenge)

Old Sarum Ley

(Map Ref: 3) - 18� mile

alignment from just north of Stonehenge to the 'Frankenbury Camp'.

(Bearing 170� 45' - the same azimuth as the Glastonbury leyline.

(2)

(More

about Old Sarum)

Glastonbury Ley (Map

Ref: 4) -

21 mile alignment running from

Brockley to Butleigh. (Bearing 170� 40')

(2)

(More

about Glastonbury)

Rudstone Ley

(Map Ref: 5)

- 10 mile alignment from Willerby

to 'South side mount'. (Bearing 142�)

(2)

(More about Rudstone)

Uffington Ley (Map Ref:

6) -

9� mile alignment running from

Uffington past Dragon Hill to a round-barrow south of the M4. Crosses

the Ridgeway and the St. Michael's ley. (Bearing 4� 20')

(2)

(More

about Dragon Hill)

Devil's Arrows -

Thornborough Leys (Map Ref: 7, 8)

- Two alignments with a 'knee-bend'

at the Devil's arrows in Yorkshire.

The first ley (Map Ref: 7), starts

North at the Thornborough henges and ends at the Devil's arrows. The

three Thornborough henges are believed to have been erected around

1700-1400 BC (2), over the

pre-existing Thornborough Cursus. While the cursus (NE-SW), indicates a

Neolithic 'linear mentality', the ley alignment follows a different

azimuth, heading approximately NW-SE past the Nunwick henge towards the

Devil's arrows 11 miles away.

The second ley (Map Ref: 8) can be said to start

with two of the Devil's arrows, and continues another 5 miles SSE (150�

35'), past the Cana henge, on towards the Hutton moor henge. The Devil's

arrows (with at least one missing today) are known to have been

transported around 7 miles to their present location

(2).

(More

about the Devil's Arrows)

(Map

of English Ley-lines)

(Please

Contact-Us

if you know of any important leylines that

should be on this page)

(Geometric

Alignments) (British

Geodesy) (Geodesy

Homepage) (Egyptian

Geodesy)

(The

Nazca Lines, Peru)

(The

World Grid) |

The

St. Michael's ley has been shown to be inter-related with several

other prominent British megaliths through geometry, astronomy and an

apparent knowledge of longitude/latitude, not least of all to

Stonehenge. Stonehenge,

whilst not being a part of the St. Michael ley, is connected with both

Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury through geometry, and also forms the crossing point

of several prominent ley-lines - both astronomical and non-astronomical. The first astronomically significant ley-line

to pass through Stonehenge was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer, and later

extended to 22 miles in length by K. Koop. This ley follows the path of the

mid-summer sunrise on a bearing of 49� 15'. (2)

The

St. Michael's ley has been shown to be inter-related with several

other prominent British megaliths through geometry, astronomy and an

apparent knowledge of longitude/latitude, not least of all to

Stonehenge. Stonehenge,

whilst not being a part of the St. Michael ley, is connected with both

Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury through geometry, and also forms the crossing point

of several prominent ley-lines - both astronomical and non-astronomical. The first astronomically significant ley-line

to pass through Stonehenge was first identified by Sir Norman Lockyer, and later

extended to 22 miles in length by K. Koop. This ley follows the path of the

mid-summer sunrise on a bearing of 49� 15'. (2)

Alfred

Watkins

first became aware of the alignment of ancient British sites in

the early 1920's, in what he

described as:- '...a flood of ancestral memory...'.

Alfred

Watkins

first became aware of the alignment of ancient British sites in

the early 1920's, in what he

described as:- '...a flood of ancestral memory...'.

John

Michel

John

Michel