|

Location:

Chaco canyon,

Albuquerque,

New Mexico. |

Grid Reference:

36� 3' 37"

N, 107� 57' 42"

W |

Chaco Canyon:

(The 'Sun Dagger').

Chaco Canyon:

(The 'Sun Dagger').

Rising nearly 400 feet above the desert floor in a remote section of

ancient Anasazi territory named Chaco Canyon stands an imposing natural

structure called Fajada Butte. Along a narrow ledge near the top of the

butte is a sacred Native American site given the name Sun Dagger

that a thousand years ago revealed the changing seasons to the Anasazi

astronomers. Rising nearly 400 feet above the desert floor in a remote section of

ancient Anasazi territory named Chaco Canyon stands an imposing natural

structure called Fajada Butte. Along a narrow ledge near the top of the

butte is a sacred Native American site given the name Sun Dagger

that a thousand years ago revealed the changing seasons to the Anasazi

astronomers.

After they abandoned the canyon for unknown

reasons 700 years ago the sun dagger's secret remained hidden except to

a special few. In 1977 it was inadvertently "rediscovered" when known or

suspected rock art and petroglyphs on the butte were being studied and

catalogued.

(Click here for map of the site)

|

The Chaco Canyon Sun Dagger: |

In 1977 Anna Sofaer, an

artist, was exploring rock art in the region and came across the light

patterns on the two spirals. Suspecting that the rock arrangement and

spiral carvings might have been intentional, she returned to the site at

various dates throughout the year and, along with her colleagues, was

eventually able to establish the following facts:

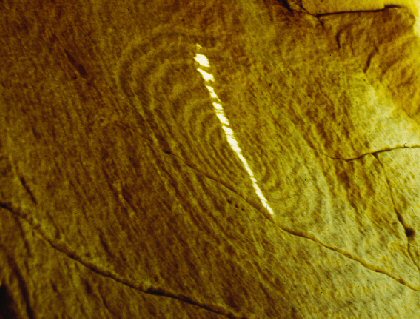

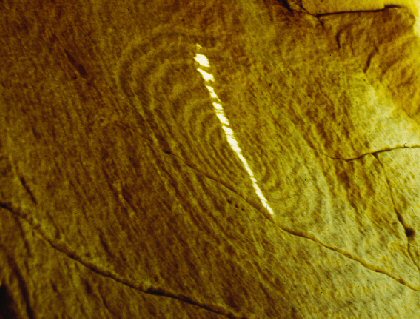

In what is now the state of New Mexico

in the south-western United States, in an area known as Chaco Canyon, are

the remains of an elaborate development of the Anasazi people who lived

in the region from about 500 to 1300 AD. Some 120 meters (400 feet)

above the canyon floor near the top of an outcropping known as Fajada

Butte, three slabs of sandstone are leaning against a rock wall creating

a shaded space. Carved into this shaded wall are two spiral petroglyphs,

one large and one small. Sunlight passes over them at various times

throughout the year as it streams through chinks between the sandstone,

but it was not until the 1970s that their true purpose was literally

illumined.

On the summer

solstice, a single sliver of sunlight�which she dubbed a "Sun

dagger"�appeared near the top of the larger spiral and over a period of

18 minutes "sliced" its way down through the very center, cutting the

spiral in half before leaving it in shadow once again. On the winter

solstice, two daggers of light appeared for 49 minutes, during which

they exactly framed the large spiral.

Finally, an equally fascinating and

more complex light show occurred on the spring and autumn

equinoxes. The large spiral is

carved in such a way that, counting from the center outward to the

right, there are nine grooves. On each equinox a dagger of light

appeared that cut through the large spiral�not through its center but

exactly between the fourth and fifth grooves from the centre. In other

words, it cut exactly halfway between the centre and the outer edge of

the spiral, just as the equinoxes cut the time between the solstices

exactly in half. Meanwhile, a second dagger sliced through the centre of

the small spiral.

These "light shows," which presumably

had been going on for centuries, continued for several years after their

rediscovery. However, in 1989 it was found that the granite slabs had

shifted. The alignments that had apparently been arranged so carefully

by the Anasazi were no more.

Similar light displays marking the

solstices and/or equinoxes can be found at other locations in the

southwestern United States and Mexico. In another Anasazi ruin in

Hovenweep National Monument near the borders of Utah and Colorado, light

beams also illuminate spiral petroglyphs on the summer solstice. At

Burro Flats in Southern California, a winter solstice Sun points a

finger of light to the center of five concentric rings in an early

Chumash rock art display. In a Tipai shrine known as La Rumorosa in Baja

California on the western coast of Mexico, a dramatic display can be

witnessed on the winter solstice when a "dagger" of light appears to

shine from the eyes of a figure painted on a shaded rock wall.

(1), (2)

|

The Moon-dagger.

Moonlight

generally creates the same patterns on the spirals as the sun, on

nights when the moon is between first and third quarter. The

periodic changes in these patterns reflect the complexity of the

moon's apparent motion, and certain combinations of patterns are

associated with specific lunar eclipses.

Lunar observations.

The patterns formed at

night by moonlight shining between the slabs are just as clear and

as noticeable as those formed by the sun, and we easily recorded

them on several nights near full moons (Fig. 10). It is not

necessary to make a detailed record of these patterns for most

positions of the moon, since at a particular point in the sky it

will form the same light patterns on the spirals as the sun would

at the same point. When the moon's declination is between + 23.5�

and - 23. 5� (the solar extremes) we can thus predict the patterns

formed by its light by knowing those formed by the sun at the same

declination. But the moon's declination can vary outside the solar

limits, up to +/- 28.5� over part of an 18.6-year cycle, and

whenever it lies beyond the extremes of the sun's declination we

have no corresponding solar data. Since this periodic extreme in

the moon's declination will not be reached again until 1987, we

cannot yet make direct observations of the patterns formed by the

moon at such declinations. As discussed later in this article,

extrapolations from the solar data suggest that a significant

marking of the maximum lunar declination may occur.

(3)

|

The Stone Slabs

The three slabs stand on the sloping

ledge at the foot of the cliff, each contacting the cliff over only a

small area . On the left of slab three is a supporting buttress of

smaller rocks and under the right edge of slab one is a small supporting

rock. All the slabs and rocks of the assembly consist of the same soft

sandstone as the cliff itself. The slabs are roughly rectangular (2 to 3

m high, 0.7 to 1 m wide, and 20 to 50 cm thick) and weigh about 2000

kilograms each. The outer surfaces and tops are rounded and weathered,

the inner surfaces smooth and gently curved with sharp edges. By

comparing the matching details on the facing surfaces of the slabs, it

has been determined that these slabs once fitted together to form one

block. The place where this block was joined to the cliff face was found

by noting the strata and bedding planes and the curvature of the cliff

face). By such comparison, the original location of each slab was

found to within 1 cm, well to the left of the present locations.

Several pieces of evidence

rule against the slabs' having fallen into their present positions

naturally. First, the slabs would have had to move 2 m and more horizontally

while the centre of gravity of the three together fell only about 80 cm

vertically. In particular, the centre of slab three by itself is now only 30

cm lower than when it was attached to the cliff. Second, there are no impact

marks, either on the cliff face or on the inner edges of the slabs, to

suggest a collision. Third, the cliff face above the original location of

the slabs shows that another rock mass had broken away from there. This

higher rock could not have broken off before the slabs did. Had it broken

off with (or after) the slabs, it would have prevented them from falling

naturally to their present location. There is no evidence today of this rock

mass. Indeed the absence of rubble near the slabs is unusual on the butte,

where fallen rock is found below other such cliffs. Fourth, the slabs are

set firmly in place on a rocky ledge and are partially supported by

buttressing stones. We conclude that moving and setting the slabs in their

present position involved deliberate human intervention.

|

Disaster struck in 1989 when erosion of the clay and

gravel around the base of the stone monoliths caused them to slip.

As

the slabs inched down the steep slope of the butte, the sun dagger

vanished. Having unobtrusively marked the passage of seasons for

centuries; it lasted only ten years after its discovery before it was

lost forever.

The loss of the sun dagger prompted the World

Monuments Fund to add Chaco Canyon--now known as Chaco Culture National

Historical Park--to its Most Endangered Monuments list in 1996.

A digital model of the original structure has now been

developed and efforts are underway to restore the monument.

|

The Anasazi - A Cultural Background

Indications that the Fajada Butte solar

marking construct was developed within the period A.D. 950 to 1150 are

the planning skills and solar interests exhibited by the Chaco occupants

at that time.

(3)

The canyon contains the ruins of the largest

pre-Columbian "city" in what is now the United States.

Several factors show that the Anasazi

inhabitants of Chaco developed the construct between A.D. 900 and 1300

(the approximate date of Pueblo abandonment of the canyon) and indicate

that the specific time was between A.D. 950 and 1150, the period of

greatest population and development in the canyon.

Certain rock art sites of the ancient

Pueblos are reported to mark solar positions by the placement of designs

to receive shadow and light formation at the rising and setting of the

sun at solstice or equinox, and one such site includes a spiral design.

Two petroglyph sites on Fajada Butte are marked with shadow and light

changes at the time of solar noon at summer solstice, and one of these

includes a spiral design. The spiral is frequently found in association

with ancient Pueblo petroglyphs of sun imagery. It is identified with

the Anasazi rock art style prior to A.D. 1300. Examples of architecture

of the same period have openings that channel light so that it shines on

key features of the structures such as doorways, niches, and corners at

the solstices and equinoxes

(3)

The site's nine "great houses," the largest of

which stood five stories high and had 650 dwelling rooms and 37

ceremonial kivas, along with some 3,500 smaller structures in and

around the canyon, may have housed up to 10,000 people at a time.

Chaco was the hub of a network of roads-at least 20 of them, each

nearly 30 feet wide-that radiated in all directions for distances of

up to 100 miles, suggesting that the site may have been a part-time

home to pilgrims from other Anasazi settlements who came here for

religious ceremonies, trade, or both.

A new study of the Southwestern landscape has

revealed that three of the region's largest and most important ancient

centers were linked by a 450-mile meridian line - Chaco Canyon, in New

Mexico; Aztec Ruins, 55 miles due north near the Colorado state line;

and Casas Grandes, 390 miles due south in Chihuahua, Mexico. Chaco and

Aztec were also connected along the meridian by a road known today as

the Great North Road (see ARCHAEOLOGY, January/February 1994).

(Other Mexican Sites)

(More about Archaeo-astronomy)

|

Rising nearly 400 feet above the desert floor in a remote section of

ancient Anasazi territory named Chaco Canyon stands an imposing natural

structure called Fajada Butte. Along a narrow ledge near the top of the

butte is a sacred Native American site given the name Sun Dagger

that a thousand years ago revealed the changing seasons to the Anasazi

astronomers.

Rising nearly 400 feet above the desert floor in a remote section of

ancient Anasazi territory named Chaco Canyon stands an imposing natural

structure called Fajada Butte. Along a narrow ledge near the top of the

butte is a sacred Native American site given the name Sun Dagger

that a thousand years ago revealed the changing seasons to the Anasazi

astronomers.