|

***In respect

for tradition, no photos of Aboriginal people have been used in this

article***

Aborigines:

(Indigenous Australians).

Aborigines:

(Indigenous Australians).

Indigenous

Australians migrated from Africa to Asia around 70,000 years ago,

and arrived in Australia around 50,000 years ago.

(5)

Dispersing across the Australian

continent over time, the ancient peoples expanded and differentiated

into hundreds of distinct groups, each with its own language and

culture. Four hundred and more distinct Australian Aboriginal

groups have been identified across the continent, distinguished by

unique names designating their ancestral languages, dialects, or

distinctive speech patterns.

(4)

The

Australian

Aborigines

represent

the oldest

example of continuous

human

culture in

the world.

The

remarkable

longevity of

their

culture is unique in the modern world, and raises several

fundamental questions about the path that 'Western civilisation' is

currently following.

Quote by: The

Venerable E. Nandisvara Nayake Thero. Dr, PhD.

"To those who judge the degree of a culture by

the degree of its technological sophistication, the

fact that the Australian natives live in the same

fashion now as they did thousands of years ago may

imply that they are uncivilised or uncultured.

However, I would suggest that if a civilization be defined by

the degree of polishing of an individual's mind and the building

of his or her character, and if that culture reflects the

measure of our self-discipline as well as our level of

consciousness, then the Australian Aboriginals are actually one

of the most civilized and highly cultured peoples in the world

today." (1)

The Origins of Australian Aborigines:

In a genetic

study in 2011, researchers found evidence in DNA samples taken

from strands of Aboriginal people's hair, that the ancestors of

the Aboriginal population split off from the ancestors of the

European and Asian populations between 62,000 and 75,000 years

ago - roughly 24,000 years before the European and Asian

populations split off from each other. These Aboriginal

ancestors migrated into South Asia and then into Australia,

where they stayed, with the result that, outside of Africa, the

Aboriginal peoples have occupied the same territory continuously

longer than any other human populations. These findings suggest

that modern Aboriginal peoples are the direct descendants of

migrants who arrived around 50,000 years ago

(3)

Both archaeology and the genes of aboriginal Australians suggest

that a mere 15,000 years were required for humanity to spread from

its initial toehold outside Africa, on the Arabian side of the

straits of Bab el Mandeb, to the Australian continent. The first

Immigrants

thus arrived about 45,000 years ago. A recent study by Irina Pugach of

the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig,

and her colleagues, which has just been published in the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

has apparently resolved the matter. About 4,000 years before

Europeans arrived, it seems that a group of Indian adventurers

(from the same time as the great Indus Valley Civilisation)

chose to call the place home. Unlike their European successors,

these earlier settlers were assimilated by the locals. And they

brought with them both technological improvements and one of

Australia�s most iconic animals, the Dingo.

(2)

(More

about the Indus Valley Civilisation)

The Arrival of Europeans:

The first recorded outside contact with Aboriginals

was with Dutch sailors such as William Janszoon and

Dirk Hartog in the early 1600�s. They were

travelling from Holland to the Dutch Colonies in

Indonesia, (the Spice Islands), and decided to leave

the 'Island' alone. Captain Cooks

'discovery' of 'Terra Nullius' (Uninhabited Earth)

was over 100 years later in

1770. It was estimated over 750,000 Aboriginal

people inhabited the island continent in 1788.

(8)

with over 700 languages spoken

(11).

As is seen in many of the European colonisations,

warfare wasn't a necessary strategy for domination as

the locals had no resistance to the deadly viruses

carried by the sailors and convicts such as smallpox,

syphilis and influenza. In less than a year, over half

the indigenous population living in the Sydney Basin had

died from European diseases.

'Every boat that went down the harbour found them

lying dead on the beaches and in the caverns of the

rocks� They were generally found with the remains of

a small fire on each side of them and some water

left within their reach'. (Lieutenant Fowell,

1789).

The

prevailing attitude of the time was that 'indigenous

peoples' were regarded as being soul-less

creatures, closer to animals than people. The American

Indians had already suffered the same disgrace, and

without resistance the following centuries brought about

the almost complete cultural decimation of the

aborigines. In 1804, settlers were authorised to shoot

unarmed Aboriginal people, following which the wholesale

slaughter of Aborigine culture began.

(13)

'I have myself heard a man, educated, and a

large proprietor of sheep and cattle, maintain that there was no

more harm in shooting a native, than in shooting a wild dog. I

have heard it maintained by others that it is the course of

Providence, that blacks should disappear before the white, and

the sooner the process was carried out the better, for all

parties. I fear such opinions prevail to a great extent. Very

recently in the presence of two clergymen, a man of education

narrated, as a good thing, that he had been one of a party who

had pursued the blacks, in consequence of cattle being rushed by

them, and that he was sure that they shot upwards of a hundred.

When expostulated with, he maintained that there was nothing

wrong in it, that it was preposterous to suppose they had souls.

In this opinion he was joined by another educated person

present'. (Bishop Polding, 1845)

In 1920, the

resident population of Aborigines was calculated as low as 60,000,

and by 1940, Europeans composed 99% of Australian population.

(13). In 1967 after a federal referendum on the

topic, Aborigines became citizens and were allowed to vote

in state and federal elections. Recent government statistics

counted approximately 400,000 aboriginal people, or about 2% of

Australia's total population. (9)

(517,000 / 2.5%)

(12)

Descriptions and images of Aboriginal lifestyle at

the time of the European 'arrival' reveals a unique look at the

way humans survived around the ancient world before complex 'civilisations'

became the norm for people living in across the larger Eurasian

continental landmass.

However, in contrast to this system, the Australian Aborigines had

retained the same similar practices, tools, methods etc as were

being found in archaeological digs

from around the ancient world from 50,000 years and before.

The traditional Aboriginal way of life was

nomadic hunter-gathering, with small groups moving around the land

depending on the season and availability of resources. The nomadic

lifestyle has certain restrictions associated with it such as the

number of possessions one can carry, and a strong dependence on

natures harvest but it also restricts the development of industry,

agriculture, townships, cities and many of the most important

foundations upon which complex civilisations are built. The intimate

connectivity with nature and the land is one of the reasons for the

length of their survival, as seen in other similar cultures such as

the North American Indians who bear several striking similarities in

terms of their relationship with the land. The European perception

of Australia as 'Terra Nullius' clearly extended to the Aboriginal

population for a long time as their near annihilation proves.

However, the fact that their culture has existed for such an

incredibly long time has not gone unnoticed by everyone, and our

judgement of their wisdom is now in question as the civilisations of

the modern world are being tested by their veracity for consumption

and greed.

A former professor

of comparative religion at Madras University, as well as director of

the Maha Bodhi Society of Sri Lanka, chief Sanghanayaka of the

Theravada Order of Buddhist monks in India and secretary general of

the World Sangha Council, Dr. Nandisvara had recently returned from

a research expedition with an anthropological team in Australia,

where he had lived for some time with a native Aboriginal community.

In his report, Dr. Nandisvara makes the following statement:

"To those who judge the degree of a culture by

the degree of its technological sophistication, the

fact that the Australian natives live in the same

fashion now as they did thousands of years ago may

imply that they are uncivilized or uncultured. However, I would suggest that if a civilization

be defined by the degree of polishing of an

individual's mind and the building of his or her

character, and if that culture reflects the measure

of our self-discipline as well as our level of

consciousness, then the Australian Aboriginals are

actually one of the most civilized and highly

cultured peoples in the world today."

(1)

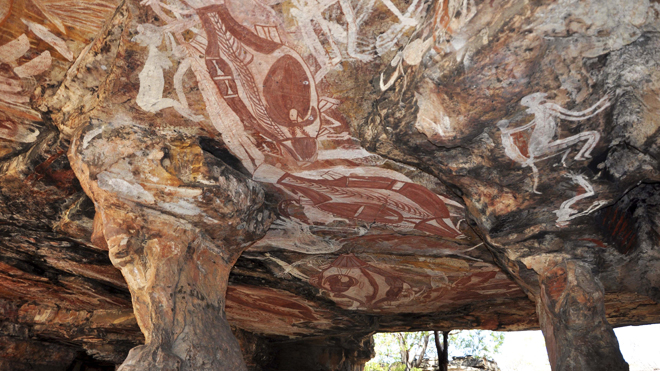

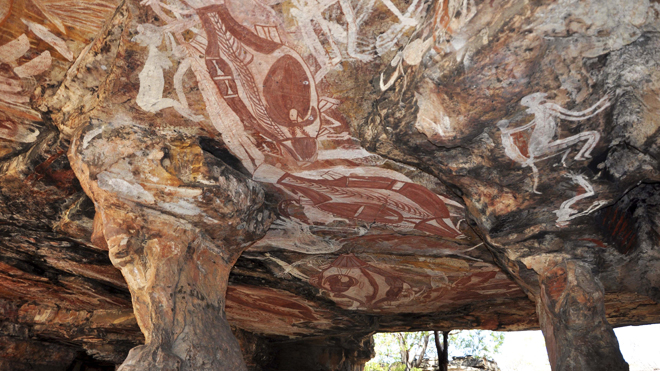

Aboriginal Art:

Contemporary

Aboriginal art is typified by 'dotted' painting, a system which was

developed in the 1970's and which became an immediate and lucrative

seller in the international market. It has been suggested that this

type of art was designed as a means of disguising the 'sacred' or

'restricted' parts of their stories, but whatever the truth, it is

now recognised as the dominant modern form of Aboriginal art. In

contrast, the Australian continent is covered with Aboriginal cave

art dating back tens of thousands of years. The oldest art is

currently accepted as being over 28,000 years old.

Article: The Guardian Online. (June, 2012)

'Australia's

Oldest Artwork Found'

'An

archaeologist says he has found the oldest

piece of rock art in Australia and one of

the oldest in the world: an Aboriginal work

created 28,000 years ago in an outback cave.

The dating of one of the thousands of images

in the Northern Territory rock shelter,

known as Nawarla Gabarnmang, will be

published in the next edition of the Journal

of Archaeological Science.

The

archaeologist Bryce Barker, from the

University of Southern Queensland, said he

found the rock in June last year but had

only recently had it dated at the

radiocarbon laboratory of New Zealand's

University of Waikato. He said the rock art

had been made using charcoal, so radiocarbon

dating could be used to determine its age;

most rock art is made with mineral paint, so

its age cannot accurately be measured.

Barker said

the work was "the oldest unequivocally dated

rock art in Australia" and among the oldest

in the world'.

(Link

to Full Article)

The Rock-shelter

known as Nawarla Gabarnmang, shows occupation for over 40,000 years.

The ancient sites which mark the resting place or activity of the supreme

beings in the Dreaming have become special or sacred places. These are the places of

the spirits of creation, where their spirit lives on, totem sites,

with meaning described by the stories for that place, and the place

from which the spirit of the new born child comes. Through the

totemic site an Aboriginal person comes to have identity, an

understanding of his/her relationship with the natural world and

other human beings.

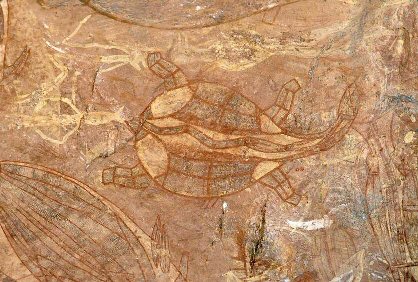

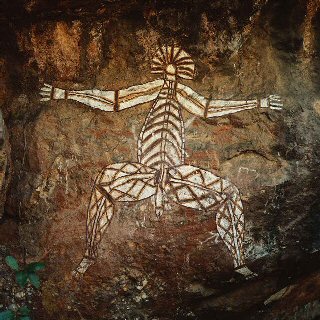

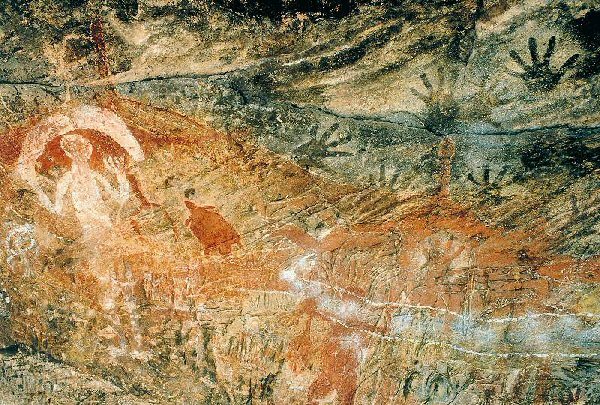

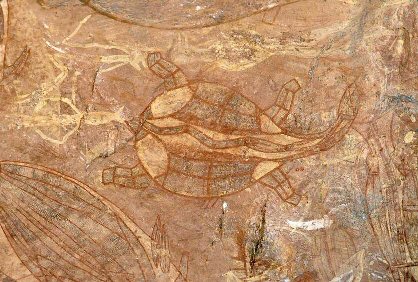

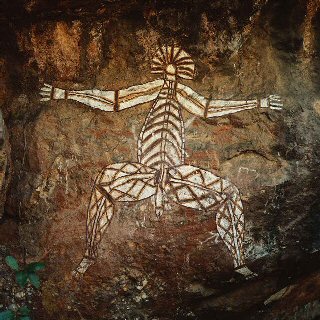

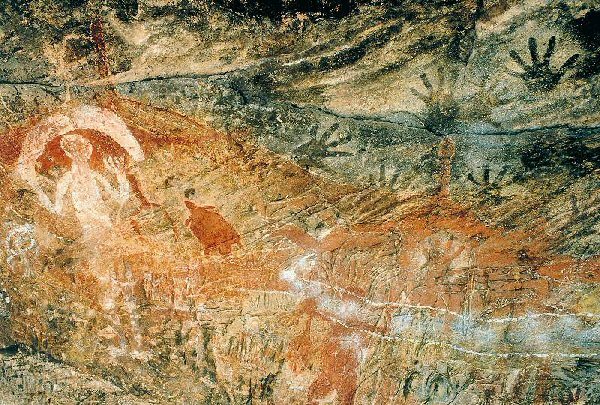

Other Examples of

Aboriginal Art.

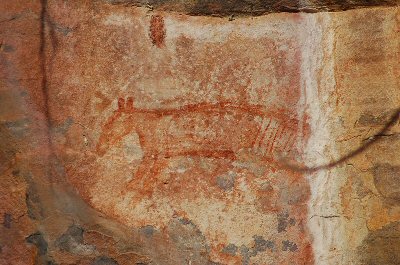

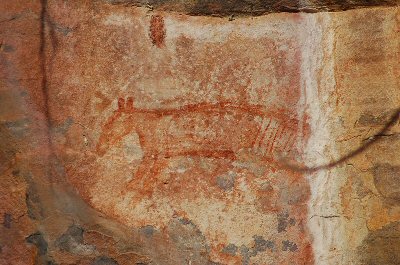

Platypus Totem at

Ubirr (left). Lightning God, Kakadu c. 6,000 BC (right)

Note the

Hand-prints, common in Aboriginal Art, as in Cave-art around the

Palaeolithic world. The European tradition of having missing

fingers is noticeably absent Aboriginal Hand-prints.

For thousands of

years Aborigines have recorded their culture as

rock art.

Their art shows images of the environment, such as the plants and

animals, including images of animals believed to have become extinct

20,000 years ago. For example, in the Wellington Range, the thousands of Aboriginal

artworks adorning cliffs and caves include a painting of the extinct

dog-like creature, the thylacine, made in a style that is at least

15,000 years old. (14)

Extinct Thylacine rock art at Ubirr: c. 15,000 BP.

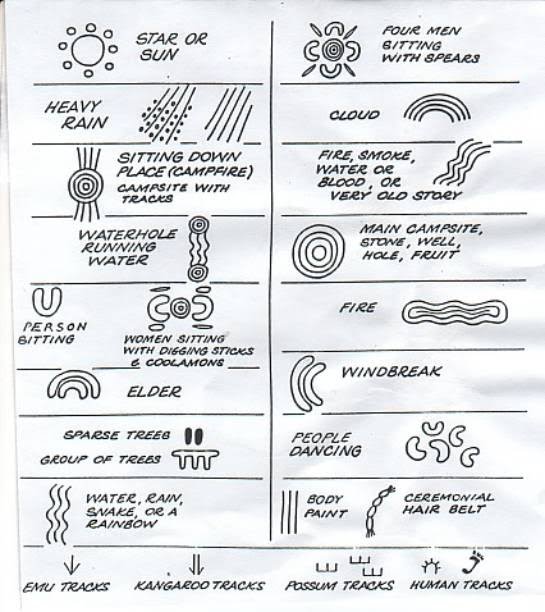

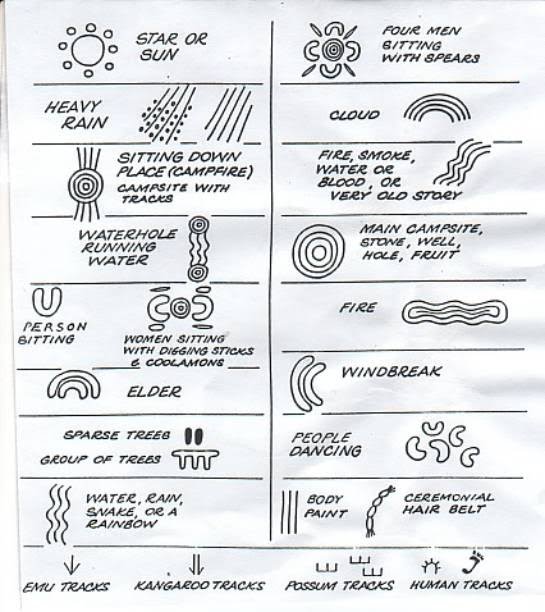

Aboriginal Script.

Although lacking a

formal written language, aboriginal art contains a series of

iconograms with specific meaning. These symbols are included into

paintings which describe events or stories from the dreamtime, and

can be seen as a basic form of language to those who understand

their meaning.

Symbols used in Aboriginal art used

to convey meaning.

Many of these symbols can be seen to

share similarities with the Palaeolithic set of symbols recognised

by Von Petzinger, following her innovative study of common

Palaeolithic symbols in European rock-art.

(More about

Palaeolithic Writing)

(Cave Art Homepage)

Healing:

'In almost all Aboriginal

belief systems, each person has three aspects which make

up his or her whole being. Those are the body, the mind

and the spirit. It is said that for Aboriginal people to

heal from whatever ails them, all aspects of their being

need to be treated�not just one. In that respect, the

Aboriginal belief is in the holistic treatment of the

person. Aboriginal healers, when called upon to minister

to a sick person, do not only administer medicines to

the body, but also conduct spiritual ceremonies for the

spirit and counsel the person to help clear his or her

mind of the effects of the sickness.

In Aboriginal beliefs, if

only the body is treated, then healing cannot take place

properly. If the body becomes ill, then the spirit and

mind also are affected. In the same way, it is believed

that before the body becomes sick, there are often signs

of the impending sickness apparent in the mental or

spiritual status of the person. Preventive steps thus

can be taken by addressing the person�s spiritual needs

early on. Keeping the spirit strong was seen as

practising preventive medicine. Elders, and people who

know of traditional ways of healing, are considered very

important and are respected highly by Aboriginal people.

Some

Aboriginal elders believe that Aboriginal people who are

ill must have all three aspects healed fully in the

Aboriginal way. Some have said that if an Aboriginal

person goes to a non-Aboriginal doctor, then that person

cannot be healed properly in the traditional way, since

traditional healing methods and modern medicine do not

mix. Others believe that if medical doctors are treating

the person�s body, then traditional Aboriginal healers

can and must attend to the treatment of the person�s

mind and spirit. In the same way, if the person is

receiving psychiatric treatment from a psychiatrist,

then his or her physical and spiritual needs still can

be met through traditional healing methods. In this way,

elders believe that there is always room for traditional

methods of healing to take place'.

(7)

(Healing Homepage)

Rituals of Death:

'Sorry Business'.

The

primary traditional burial

practice is to leave the corpse laid

out on an elevated wooden platform, covered in leaves and branches,

and left several months for the flesh to rot away from the bones.

The secondary burial is

when the bones are collected from the platform, painted with red

ochre, and then dispersed. (10)

Some Aborigines bury their dead

some cremate them, some place the bodies on platforms or in trees or

caves to conceal them. Many different practises are performed to

ensure that the spirits of the dead would not cause mischief or

sadness within the language group. In many places mounds of dirt,

bark, sticks and other natural objects were built between the grave

and campsite to ensure that the bad spirits of the dead didn't haunt

the living.

A person's possessions and weapon's are often disposed of or buried

with them during the ceremony. In some areas burial poles are

erected at burial grounds or stencil markings and paintings would

show where loved ones were buried in caves. Ceremonies last days,

weeks and even months depending upon the beliefs of the language

group. During these ceremonies often strict language rules apply.

With close family members restricted to not being able to talk for

the whole period of mourning. Members of the family with the same

name as the deceased were required to change their names.

The tradition not to depict dead people or voice their (first) names

is very old. Traditional law across Australia said that a dead

person�s name could not be said because you would recall and disturb

their spirit. After the invasion this law was adapted to images as

well.

The Origin Myth:

The common

underlying thread of all Aboriginal origin myths is a reference to

the 'Dream-time' or 'creation period'.

At the

beginning of time the earth looked like a featureless, desolate

plain. Nothing existed on the surface.

Baiame, or the Maker of Many Things as

some called him, called the Dreamtime ancestors from under the

ground and over the seas. With them, life came to the barren, flat

plains. Some of the Dreamtime ancestors looked like men or women,

others like the animals or creatures, which descended from them, but

the Dreamtime ancestors could also change their shape from one form

to another.

After emerging from their eternal slumber, the beings � referred to

as totemic ancestors (such as Wallaby Dreaming and Emu

Dreaming etc) � moved about the earth bringing into being the

physical features of the landscape. Mountains, sandhills, plains

and rivers all arose to mark the deeds of the wandering totemic

ancestors. Not a single prominent feature was created which was not

associated with an episode of the supernatural beings.

Biame, the

Awabakal Supreme Being.

For the Awabakal, the supreme being who created their world is

Biame, part human and part kangaroo or wallaby. In a rock cave on

Bulgar Creek near Singleton Biame is depicted in a drawing

approximately eight feet high as if his legs and arms are lying on

the ground (See below). The perpendicular lines drawn under the arms, three on

right and four on the left, represent the seven tribes of the region

for whom this supreme being had great significance: Worimi, Awabakal,

Wonarua, Gamillaroi, Darkinjung, Gringai (Matthews

1893;

Heath 1998). The Dreaming:

The Dreamtime is a widely used, but not

so well

understood term describing the key aspects of Aboriginal spiritual

beliefs and life. It refers not to historical past but a fusion of

identity and spiritual connection with the timeless present. The

Aboriginal concept of time connects past actions and people with

present and future generations. Time is circular, not linear, as

each generation relives the Dreaming activities. There were many myths and rituals connected to both the ancestors and the creators of the world, none of whom ever died but

merged with the natural world and thus remained a part of the

present. These myths and rituals, signifying communion with nature

and the past, were known as the Dreaming or the Dreamtime, and

reflected a belief in the continuity of existence and harmony with

the world.

The term 'Dreaming'

in reference to Aboriginal religious philosophy was adopted by the English anthropologists Spencer and Gillen from their research

published as The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899). Arrente

elders had endeavoured to explain the basis of their religious

philosophy to them by describing the alcheringa, their religious

philosophy, as the mythic times of the ancestors of the totemic

groups. They had not initially grasped its full meaning and later

Spencer explained that this past mythic time was only a part of the

meaning of alcheringa, that it also meant "dream". Since then it was

commonly adopted by Aboriginal people across Australia that the

ancestral heroes, their past times and everything associated with

them is encapsulated in the English language word "Dreaming". Thus

Aboriginal philosophy comes from the time of creation when the world

was "mixed up" and not at all like it is in modern times.

Supreme beings, great ancestors who were human, animal and bird all

at the same time, anthropomorphs, were powerful enough to create

order in this chaos. These ancestral heroes are responsible for life

itself; life that arose in a time when all the natural species, the

land and humans, were part of the same ongoing life force. They had

powers to turn themselves into geographic or natural features, they

descended into the ground and reappeared as a species of bird or

animal, or as a waterhole, or they ascended into the sky and became

constellations. As they moved around they created all the species,

humans, the landscape and all the features of it, then they tended

to settle down and remain as a feature of the landscape.

(6)

Aboriginal Mythology as a Historical Narrative:

An Australian

linguist,

R. M. W. Dixon, recording Aboriginal myths in their

original languages, encountered coincidences between some of

the landscape details being told about within various myths,

and

scientific discoveries being made about the same landscapes.

In the case of the

Atherton Tableland, myths tell of the origins of

Lake Eacham,

Lake Barrine, and

Lake Euramo. Geological research dated the formative

volcanic explosions described by Aboriginal myth tellers as

having occurred more than 10,000 years ago.

Pollen fossil sampling from the silt which had settled to

the bottom of the craters confirmed the Aboriginal myth-tellers' story.

'It is said that two newly-initiated men broke a taboo

and angered the rainbow serpent Yamany, major spirit of the area ... As a

result 'the camping-place began to change, the earth under the camp roaring

like thunder. The wind started to blow down, as if a cyclone were coming.

The camping-place began to twist and crack. While this was happening there

was in the sky a red cloud, of a hue never seen before. The people tried to

run from side to side but were swallowed by a crack which opened in the

ground'....

After telling the myth, in

1964, the storyteller remarked that when this happened the country round the

lakes was 'not jungle - just open scrub'. In 1968, a dated pollen diagram from

the organic sediments of Lake Euramoo [Ngimun] by Peter Kershaw (1970) showed,

rather surprisingly, that the rain forest in that area is only about 7,600 years

old'. (15)

Further investigation of the material by the Australian

Heritage Commission led to the Crater Lakes myth being

listed nationally on the

Register of the National Estate,

and included within Australia's

World Heritage nomination of the

wet tropical forests, as an "unparalleled human record

of events dating back to the

Pleistocene era."

Since then, Dixon has assembled a number of similar

examples of Australian Aboriginal myths that accurately

describe landscapes of an ancient past. He particularly

noted the numerous myths telling of previous sea levels,

including:

- The

Port Phillip myth (recorded as told to Robert

Russell in 1850), describing Port Phillip Bay as once

dry land, and the course of the

Yarra River being once different, following what was

then Carrum Carrum swamp. This was an oral history that

accurately described a landscape from 10 000 years ago.

- The

Great Barrier Reef coastline myth (told to Dixon) in

Yarrabah, just south of

Cairns, telling of a past coastline (since flooded)

which stood at the edge of the current Great Barrier

Reef, and naming places now completely submerged after

the forest types and trees that once grew there. This

was an oral record that was accurate for the landscape

10 000 years ago.

- The

Lake Eyre myths (recorded by J. W. Gregory in 1906),

telling of the deserts of

Central Australia as once having been fertile,

well-watered plains, and the deserts around present Lake

Eyre having been one continuous garden. This oral story

matches geologists' understanding that there was a wet

phase to the early

Holocene when the lake would have had permanent

water.

The

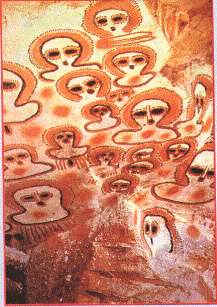

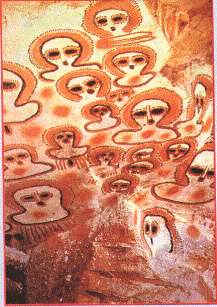

Flood Myth: The

Flood Myth:

In

Aboriginal mythology there are beings called the Wondjina. They were

rain spirits who were also involved with creation. They are said to

come from the sky and paint pictures of themselves on cave walls.

At one point in time it is said, the Wondjina were angry at how people were

behaving in the world, so they caused a worldwide flood. This was

caused by them opening their mouths, and when

they did this rain would never cease. After the floods had killed

all the humans, the Wondjina recreated everything.

Obviously the Wondjina had to keep their mouths shut so that the

world wouldn�t flood again. After doing this so long, their mouths

disappeared, which is why in most images of them they have no mouths.

The Wondjina eventually they lost their form and became more like

the spirits that you and I think of. They are said to still exist in

waterholes, ponds.

(Other

Versions of the Great Flood Myth)

The Rainbow Serpent:

The Rainbow

Serpent is a common

motif in the art and mythology of Aboriginal

Australia. There are innumerable names and stories associated with

the serpent, all of which communicate the significance and

power of this being within Aboriginal traditions. The

Rainbow Serpent's mythology is closely linked to

land, water, life, social relationships and

fertility. It is known both as a benevolent protector of its people and as a malevolent

punisher of law breakers.

The

Arnhem Rainbow Serpent.

The Rainbow Serpent is seen as the

inhabitant of permanent

waterholes

and is in control of life's most precious

resource, oils and waters. The Rainbow Serpent has been

understood as male by some traditions and female by others.

The sometimes unpredictable Rainbow Serpent (in contrast to

the unyielding Sun) replenishes the stores of water, forming

meandering gullies and deep channels as the Rainbow Serpent slithered

across the landscape.

Dreamtime stories tell of the great spirits and totems

during creation, in animal and human form they moulded the

barren and featureless earth. The Rainbow Serpent came from

beneath the ground and created huge ridges, mountains and

gorges as it pushed upward. The Rainbow Serpent is known as

Ngalyod by the

Gunwinggu and Borlung by the

Miali. The Rainbow Serpent is understood to be of

immense proportions and inhabits deep permanent waterholes.

Serpent stories vary according to

environmental differences. Tribes of the

monsoonal areas depict an epic interaction of the Sun,

Serpent and wind in their

Dreamtime stories, whereas tribes of the central desert

experience less drastic seasonal shifts and their stories

reflect this.

Song Lines:

There are many

different methods of pre-literate navigation that have been

documented around the ancient world. The Aboriginal fusion of

navigation and oral mythological storytelling is likely to have

been a common method in the past and goes a long way to explaining

the development of sacred landscapes.

Song-lines, also called Dreaming tracks, are paths across

the land (or sometimes the sky)

which mark the route followed by localised

'creator-beings' during the

Dreaming. The paths of the Song-lines are recorded in

traditional songs, stories, dance, and painting. By singing the songs in the appropriate sequence,

Indigenous people could navigate vast distances, often

travelling through the deserts of Australia's interior.

The continent of Australia contains an extensive system

of songlines, some of which are of a few kilometres,

whilst others traverse hundreds of kilometres through lands of many

different Indigenous peoples.

A

knowledgeable person is able to navigate across the land

by repeating the words of the song, which describe the

location of landmarks, waterholes, and other natural

phenomena. In some cases, the paths of the

creator-beings are said to be evident from their marks,

or

petroglyphs, on the land, such as large

depressions in the land which are said to be their

footprints.

Since a Song-line can span the lands of several

different language groups, different parts of the song are said to

be in those different languages. Languages are not a barrier because

the melodic contour of the song describes the nature of the land

over which the song passes. The rhythm is what is crucial to

understanding the song. Listening to the song of the land is the

same as walking the Song-line and

observing the land.

In some cases, a song-line has a particular direction,

and walking the wrong way along a song-line may be a

sacrilegious act (e.g. climbing up

Uluru where the correct direction is down).

Traditional Aboriginal people regard the land as sacred,

and the songs must be continually sung to keep the land

"alive".

(Prehistoric

Pacific Islanders)

(Palaeolithic

Wisdom) |

The

Flood Myth:

The

Flood Myth: