|

European Megalithic Complexes:

(Form and Function)

European Megalithic Complexes:

(Form and Function)

A look at the

most prominent concentrations of European megalithic sites.

Household names such as the Orkney

Islands, Boyne Valley, Carnac, Salisbury and Malta, were all functioning at

the same period of time (c. 3,100 - 2,400 BC), at the height of the

Neolithic period. Although they are scattered over a thousand miles of

coastline, and cross several localised Neolithic regions, these

'complexes' are united by a set of specific and contemporary cultural

features, a fact which suggests that - at the very least, they offered a

common socio-religious experience to the people who lived alongside them.

The construction of so many grandiose complexes

at this time united

the Neolithic people in an important cultural way unseen

before in Europe. Their existence acted as a stabilising anchor, as

demonstrated by the fact that in many cases the very same locations

were re-used over and again for thousands of years. The development of such

large-scale construction programs also created a

requirement for specialised skills and crafts. But how are we to view these complexes

today. Were they the prehistoric equivalent of modern cities, Astro-religious

centres, what drove the western European Neolithic people to build so many

civil-scale structures, and how are we to understand such a choreographed event

through modern eyes.

| Examples

of European Mega-Complexes: |

The Following is a brief description of some of the better known

prehistoric European complex's.

The Orkneys complex, Scotland.

(Includes Brodgar,

Stennes,

Maes Howe,

Skara Brae).

(Map of the Orkneys

Complex)

The Orkneys shows a

continuous Neolithic occupation from 3,500 onwards, with construction

work on Stennes, Skara Brae and Brodgar starting at around 3,100 BC

with Maes Howe being built soon after at around 2,800 BC. The Orkneys

resists the standard description of the priorities of Neolithic

communities in Europe at this time (in terms of survival), but is a classic example of a

'complex', perhaps being one of the last to be built by what appears

to be a northerly immigration along the Atlantic coast by people

casually termed 'Boat-people' or 'Grooved-ware-Beaker' people.

At the latitude of

the Orkneys the major lunar standstills north becomes almost

circumpolar, (neither rising nor setting - with the effect that the

moon 'rolls' along the horizon). Because the Earth�s axial tilt

has changed by nearly half a degree since the majority of the stone

circles were built, this effect is no longer accurate and the latitude today would have to be 63�

north for a lunar standstill north to be truly circumpolar (3)

Alexander Thom - 1969. Megalithic

Lunar Observatories.:

'The moon from the

Shetland Isles today is almost circumpolar, (when the moon is at its

furthest north). In megalithic times, because of the greater

obliquity - the moon from the high ground from northern parts of

Island would have been circumpolar'.

Thom noted that the natural

features in the surrounding landscape seemed to serve as distant

markers for the rising and setting of the moon. A sightline to the

cliffs of Hellia on Hoy, for example, seemed to mark the minor

southern setting of the moon, while a notch on Mid Hill, to the

south-east, defined the minor southern moonrise. (6)

The Orkneys'

'complex' is approximately 1.5�

lower in latitude than the Shetlands, so the the moon would have still

appeared to be partially circumpolar. Even today, Callanish on

the Hebrides (58� N), still shows a similar effect with the

Southern standstill.

(More about the Orkneys complex)

The Salisbury complex. England. -

(Includes

Avebury, Silbury Hill,

Sanctuary,

Stonehenge etc.. etc..)

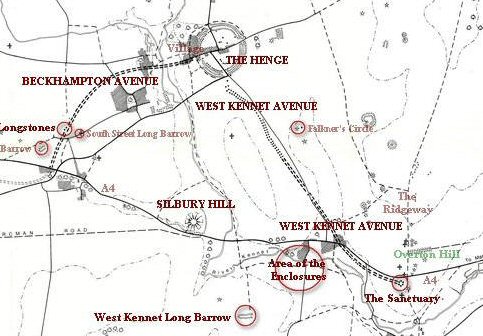

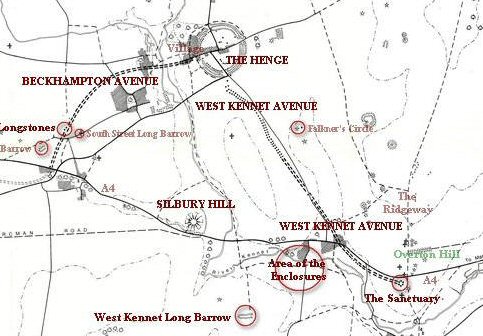

(Map

of the Extended Salisbury Complex)

The area Windmill Hill Henge, West Kennet

and the Stonehenge Cursus all gave radiocarbon dates of around 3,500 BC.

Avebury began at around 3,000 BC, and the first phase of Silbury

Hill came a couple of hundred years later at around 2,750 �95 BC. The

significance of the location lies in its latitude, (51�

25' 40'' N, both

1/7th the circumference of a circle and 4/7th's of 90�). The monuments

around Avebury can be viewed as the Northern part of a super complex

which includes Stonehenge, Durrington Walls, Woodhenge and the

Cursus.

It is a curious

fact that

Stonehenge and the Sanctuary are separated by exactly 1/4 of a degree of latitude,

and both lie on the same line of longitude. The incorporation of

such an earthly measurement into two contemporary sites (The

Sanctuary being the start-point of the Avebury avenues, and

Stonehenge being at the end of the Southern avenue leading from the

River Avon. The separation of other prominent megaliths from

these two points by units of degrees, opens the debate that this

location was chosen to represent a prehistoric meridian.

(More

about the Salisbury Complex)

The Boyne Valley complex, Ireland.

(Includes: Newgrange,

Knowth,

Dowth)

(Map of the Boyne Valley Complex)

The radiocarbon dates

for the construction and use of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth span nearly

half a millennium: (3,500 - 3,000 BC). As Ireland was already

populated by Neolithic passage-mound builders (such as

Carrowmore c. 4,600 BC), the specific

astronomical nature of these three mounds suggest that cumulative

knowledge and long term planning lie behind the layout of this ritual

centre, most probably dating back long before the construction of the

three major tombs. The Boyne-valley complex is intervisible with other

prominent megalithic sites such as: Tara

Hill, Loughcrew and

Four-knocks.

The site-to-site

bearing from the Avebury complex to Tara Hill, Ireland is 360/7.

In addition, Ireland shares another important geodetic relationship with

Avebury, which is that both the Newgrange and Avebury complexes possess

identically-sized stone circles of 103m (As does the ring of Brodgar on

the Orkneys).

(More about the

Boyne Valley)

The Carnac complex, France.

(Includes

Le Grande

Menhir Brise, Table Des Marchands,

Er lannic,

Gavrinis).

(Map of Carnac

Complex)

The concentration of

Megaliths at Carnac and the surrounding area are considered the

greatest in all Europe. The region shows several specific periods of

activity, starting slightly earlier than the British counterparts with

the first at around 5,000 - 4,500 BC (Kercado

4,700 BC), when several large monuments were

erected such as the Kercado passage mound and the Dol de Breton

alignment for example. Noticeably, at around 3,300 -3,100 BC the

region experienced a wave of construction which included the re-use of

existing monuments (i.e. The cap-stones for the

Table-des-Marchands,

Gavr'inis and

Er-Lannic tumulii (c. 3,300 - 3,100

BC), are all parts of an

original menhir from the Grande Menhir construction). The new

constructions show several specific similarities with those built at

the same time in the Boyne Valley and on the Orkneys.

(More about the Locmariaquer

Menhirs)

The Evora complex, Portugal.

(Includes Zambujeiro,

Almendres, Gruta da

Escoural).

(Map of Evora

Complex)

Home to the oldest

stone circles in western Europe, one of the most spectacular passage mounds,

and numerous other sites dating back to the Mesolithic, this region of

Portugal is now being called the 'Mesopotamia of Iberia'. The

Almendres stone circle shows different stages of development

through the 4th to 5th millennium BC.

The latitude of Evora has an astronomical

significance in that there

are only two latitudes at which the Moon's maximum declination is the

same as the latitude (meaning that at its maximum elongation it

goes through the zenith - directly overhead). These two latitudes

are 38˚ 33' N (Almendres), and 51� 10' N (Stonehenge).

(More about the Evora complex)

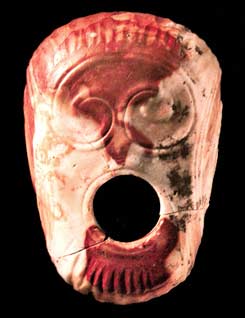

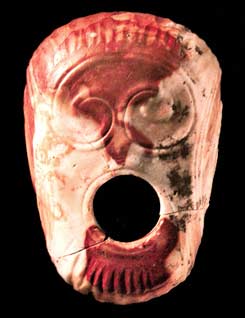

The Maltese complex.

(Includes Ggantija,

Tarxien, Hypogeum,

Hagar Qim).

(Map of Maltese Megaliths)

The Island of Malta

served as a prehistoric complex for Earth-mother worship for well over a

thousand years. The isolatory nature of the island has made it a 'Petrie

dish' of prehistoric life for researchers. Regardless of this

apparent isolation, the island retained a constant association with a

form of Earth-mother

worship, as reflected in the numerous female figurines and the

rounded, almost anthropomorphic shapes of the temples themselves. The Island of Malta

served as a prehistoric complex for Earth-mother worship for well over a

thousand years. The isolatory nature of the island has made it a 'Petrie

dish' of prehistoric life for researchers. Regardless of this

apparent isolation, the island retained a constant association with a

form of Earth-mother

worship, as reflected in the numerous female figurines and the

rounded, almost anthropomorphic shapes of the temples themselves.

The main temple

building phase on Malta was from around 3,500 - 3,000 BC, as at the

other complexes above. There are several examples of twinned temples,

of especial interest is the Ggantija - Zhagra pairing on Gozo.

It is noticeable that

the temples are represented as being covered over, which, when

combined with the internal cruciform design and presence of libation

bowls, draws a remarkable with the western European passage

mounds.

(More about the Malta)

|

Chronology of Construction: |

Having identified the most

significant concentrations of western European megaliths, and their

contemporary development, there are

several features in general that can be seen to be common amongst

them. Primarily, a route

can be traced along the western Atlantic coast from Portugal northwards past France, Ireland and

England to Scotland's most northerly point. In addition, 'Grooved ware' pottery has

been found at the Orkneys (4), Avebury/Silbury

(4), and the Boyne

Valley, at Knowth (7) and is 'almost always

found in the contexts of large henges or circles'

(4).

We are left here

with the first inklings of an idea that these complexes all appear

to result from the same wave of immigration, presumably by the 'Grooved-Ware

people', as they are commonly called today.

Although all of the above

complexes show a similar construction phase at around c. 3,100 BC and

again at 2,500 BC, many of the

locations were already in use long before that particular period of time

-

which reveals another interesting fact about these sites which is that

following the Neolithic construction phase, they appear to have been used for a short period of time only,

following which, many appear to have been effectively abandoned. This pattern of

development is in contrast to the middle-eastern sites which show a

prolonged growth from township to city state etc, which brings into

question the ultimate purpose of these sites.

|

The Complex and its Place in the Living Landscape: |

One of the most recognisable things about these

complexes is the way in which they were so sensitively built into the

landscape. They were built in such a way as to enter the 'living'

landscape, converting it into both a ceremonial and spiritual arena..

The apparently random

placement of these complexes is put into question when one begins to

look at the landscape features surrounding the monuments, and the

placement of the complexes within their settings. On the Orkneys, for

example, the ever present Hills of Hoy were used as a marker in a

'living sundial', behind which the setting-sun marked the time of year

like clockwork.

The mound of Silbury

hill, which has been dug and dug and dug again, has revealed no

incarnation

and therefore, as yet, has resisted a logical explanation for its

presence. In the centre of the structure, recent archaeology (2008), has determined

the presence of an earlier mound, suggesting that the mound

itself

may be the only purpose of the structure. It is here we can begin to see the

idea of a symbolic

representation of the 'Primal Hill of creation', being built into a

ceremonial landscape, which although being

the largest of its kind in Europe, appears almost hidden into the

folding landscape which includes Avebury, the Sanctuary, and several

other local monuments (with no inter-visibility between them

except perhaps from Wodin Hill).

The remains of ceremonial pathways and other constructions

however (i.e. Windmill hill 3,350 BC, West Kennet c.3,500 BC),

testify to the fact that this complex of sites was both connected

physically and were used together in some capacity even before

Avebury and Silbury hill (as we see them today) were built. In this

respect, these structures can be seen as a response to a perpetually

developing sacred landscape. Note for example, that the top of Silbury

hill is at the same level as what would have been a pre-existing West-kennet

long-barrow.

At all of the

complexes mentioned, it appears that water played an important part in

their placement. This statement, while seeming apparently obvious,

should not be disregarded out of hand as the presence of several

natural springs at the very base of Silbury hill for example, suggests that the

mound may have been deliberately constructed so as to be permanently

surrounded by water, again suggestive of a symbolic representation of the

'mound of creation' emerging from the 'watery chaos' of our

mythological past. While this particular feature is not observed as

obviously at all of the sites above, there certainly seems to be a

connection which deserves consideration.

In is interesting to see in this projection of a

5m rise in the water level of the nearby River Kennet transforms the

look of the complex completely, showing Silbury hill surrounded and

the ditch surrounding Avebury potentially being filled with water -

providing a possible reason for the larger outer bank, unusual in

British henges.

| Primal

Mounds and Stone Circles: |

It has been observed that several of

the largest mounds in UK are often accompanied with the presence of a

prominent stone-circle. The mound is compared to the 'mound of creation, while the stone circle is

commonly associated with astronomy. Often there are two circles

present. In terms

of construction, the Primal mound is represented in the form of

passage-mounds. In this respect, passage mounds can be seen to create a

portal between the Earth Mother and the Solar deity, through which we

can witness the 'beating heart of the universe'.

Physical entrance to the internal chambers of passage mounds invariably requires the visitor

to crouch, stoop or even crawl.. until one enters the central chamber

which is also usually raised high enough for one to stand again.

Passage mounds share a close analogy with the female

form - not just in the not just in the rounded shape of the mound itself,

but more through the way in which the mound operates with its environment,

namely in allowing the sun to penetrate its inner chambers once a year...

particularly delicately and sensitively in the case of Newgrange. The

internal chambers are often cruciform, almost appearing in the female form

itself in the Maltese temples.

(More about

Passage-mounds)

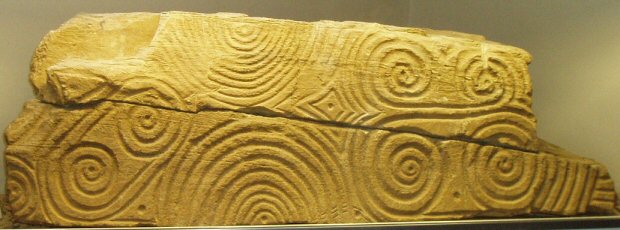

The

Gavr'inis passage mound at Lochmariaquer, France is now

permanently surrounded by water, and arguably always was - as

the bay is believed to have became flooded at around 5,000 BC.

This spectacular passage mound, contains what is considered some

of the

finest examples of European Neolithic art on its internal

stones. It also was constructed

around 3,100 BC, and shows specific design and construction similarities with the passage

mounds at the other European complexes such as Newgrange and

Maes-howe.

Directly in front of Gavr'inis passage mound is a

tiny island (which would have been connected in prehistory) with

a menhir on its crown. Just out of sight, and partially

submerged, are the remains of the Er-Lannic twin stone circles. Once again, whether by chance

or purpose, we are offered another variation on the mound-circle

theme that appears common to all complexes.

(More about Gavr'inis)

At the Orkneys

complex, The circles of Brodgar, Stennes and

the Maes-Howe mound, we are offered the perfect example of this union between mound

and circle. In the case of the Orkneys complex,

the sites were positioned so as to combine with the 'living' landscape

within which they were set, at the same time connecting with the cycles of

the sun and moon.

Maes Howe was positioned and orientated to

receive the setting sun for just several minutes of each year.

The whole complex is surrounded by water,

and a land-bridge connects the two stone circles together.

There are clear parallels between the Orkneys and the megalithic

concentration in the area of Wiltshire, where we find that the dominance

of the Avebury stone circle is mirrored in Brodgar, with a similar parallel between Silbury Hill and Maes Howe �

although the parallel

is in appearance alone, namely that of a conical mound symbolising the

'Hill of creation'.

However, this is not the only connection.

As early as forty years ago, another link was made between the two areas,

because both contained a type of pottery known as �Grooved Ware�. This

same pottery has since been found at other Neolithic sites and can now be

identified as originating from the same cultural source.

Avebury/Silbury: The Classic Mound/Circle.

The Avebury/Silbury complex also offers a classic

example of mound and circle. Both are the largest examples of their

kind and were clearly intended to be the most representative example

of Mound/Circle in southern Britain. Both Avebury and Silbury hill

were (arguably) surrounded by water in prehistoric times. It is

suggested that Sibury hill was deliberately built in such a way that

it was always surrounded by spring water. The western edge of

Silbury lies directly north of the eastern edge of the Avebury

Henge. Although the West-Kennet and Beckhampton Avenues appear to

direct traffic around Silbury Hill and not to it, there is no doubt

that it was a vital component of the sacred landscape.

Perhaps significantly, Michael Giles argues that

Silbury hill was built to represent an immense pregnant

earth-mother figure. He cites

references which suggest that the earth-mother figure was built into

the shape of other constructions at both the Orkneys and Malta.

(More about Silbury

Hill)

Other European complexes show the same symbolic combination of

mound and circle, although local variations apply:

At the Boyne Valley, the two structures were combined in

the same central monument,

Newgrange.

At Evora in Portugal, the twin circles of

Almendres and

the Zambujeiro passage mound would have

dominated the prehistoric landscape.

Malta has several examples of twinned temples, but on

Gozo, the temples of Ggantija stand only hundreds of yards from the

Xaghra stone circle, with its underground

burial chambers.

|

Other Similarities Between Complexes: |

There are several connections between these sites

which suggest that they performed similar functions and that a close

cultural connection existed between the builders of these apparently

separate complexes. It is through these cultural similarities that we

can perhaps begin to understand the motivation behind so many

'civil-scale'

building projects.

Spiral Art: Cross-cultural similarities.

It is

now common knowledge that the 'Temples' on Malta were designed and

constructed (at least in part), so as to capture a beam of

sunlight at specific times of the year, amplifying its importance upon

the holiest of holies deep within the structures. The temples are invariably

orientated to important parts of the solar year, such as the solstices

and equinoxes. Their internal design, whilst being more rounded,

conforms to the 'cruciform' design found in passage mounds across

western Europe, making them variants of each other (This same design

feature was noted by Sir N. Lockyer in relation to the pyramids and

temples of Egypt). In

addition, huge stone-cut

libation

bowls were found at the Tarxien, similar to those found in the passage

mounds of the Boyne Valley.

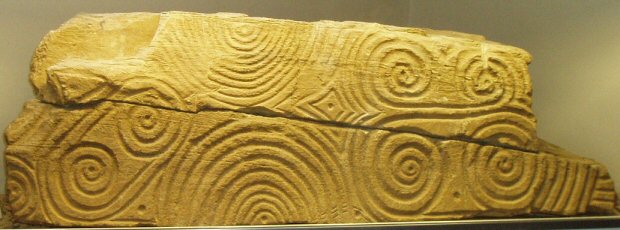

Associated with both sites is a prevalence of spiral-art,

the significance of which can

still only be guessed at.

This stone is from

Bugibba temple on Malta.

And this is one of a

pair of similar stones in the Tarxien.

Although there is no suggestion of a direct contact, there are nevertheless striking similarities between the

Maltese spiral art, and that of the Boyne Valley and Orkneys Neolithic communities as the following examples illustrate.

(More

about prehistoric Malta)

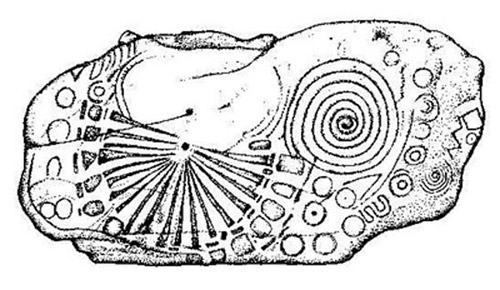

Newgrange:

The inscribed kerb-stone

that lies directly in front of the entrance to the Newgrange passage mound

has the triple spiral on the left hand side (also seen on the wall inside

the chamber). Almost identical art has been found on the Orkneys, and

variations of it can be seen throughout the ancient world.

Spiral kerbstone from Newgrange.

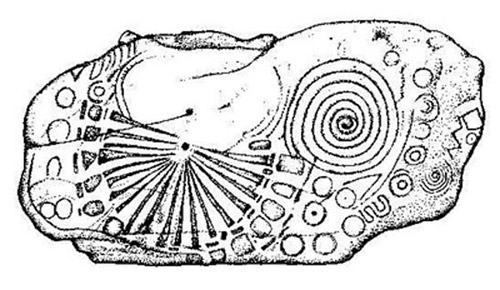

Orkneys, Scotland: A rare piece of Neolithic art

was found on a beach by an Orkney plumber :

The 6,000-year-old relic, thought to be a fragment

from a larger piece, was left exposed by storms. Local plumber David

Barnes, who found the stone on the beach in Sandwick Bay, South

Ronaldsay, said circular markings had shown up in the late-afternoon

winter sun, drawing his attention to the piece.

Archaeologists last night heralded the discovery as a

"once-in-50-years event". But they warned that a search for other

fragments in the area would be hampered by a lack of funds.

Archaeologists compared the discovery to the Westray Stone (below), a

Neolithic carved stone discovered in 1981 during routine quarrying work.

It has been in Orkney Museum for more than 25 years but is due to be

returned to the area this week and exhibited in the new Westray Heritage

Centre in Pierowall.

The 'Westray Stone', from Pierowall

(left). The Eday Manse stone, Isle of Eday.

(right).

The Westray Stone, Orkneys.

The Westray Stone was once part of a Neolithic

chambered cairn which is thought to have been destroyed in prehistory. A

second part, and two smaller carved pieces, were found the following

spring in a dig led by Niall Sharples, of the University of Cardiff.

"The stone is perhaps from a chambered tomb and could

be as old as 5,000 or 6,000 years, and would have possibly been used as

a ceremonial, sacred object. This is art made in the same style as art

from the Newgrange stone tomb in Ireland or tombs in Brittany. It's part

of this Neolithic world linked by the Irish Sea."

The stone will now be passed to Orkney Museum and

brought to the attention of the Queen and Lord Treasurer's Remembrancer

to determine if it is a treasure trove or not. Ancient objects without

an owner are automatically property of the Crown. But Mrs Gibson added:

"An object like this becomes the property of everyone."

Ref: (http://news.scotsman.com/)

This beautiful mace-head (right), was found at

Knowth. The flint itself comes from the

Orkney islands, which are by no means

the nearest source of flint to the Boyne valley. It is one of several

clues that testify to a cultural exchange between these two important

megalithic complexes, along with the style of art, exterior and interior

similarities in design of the passage mounds (Maes

Howe) and a strong astronomical theme underlying the development of

the structures.

Having identified cultural connections existed between

complexes, we now turn to their locations. We have already noted that the

locations of the Orkneys, Avebury/Stonehenge and Evora complexes all have

an astronomical relevance, but can it be that they were chosen because of

this, and if so, are there any others?

|

Geodesy, Astronomy and the European Megaliths: |

It is impossible to hide from the fact that some of

these sites appear to show a geodetic relationship to each other, a

relationship which is strengthened by the astronomical significance of

the locations of several of these complexes. But does this mean that

they were selected because of this significance.?

It is a fact that at least

three of the complexes listed above were located at latitudes of astronomical relevance. This is not

something to be ignored as it is clear that astronomy was a primary

concern of the Neolithic builders.

Associated Astro-religious belief systems.

In order for one to

observe the celestial sky accurately, one needs to choose a site with

appropriate views of the heavens, a fact which can be seen repeated in

many of the smaller megaliths (for example, the RSC's of Scotland have

been invariably shown to be orientated towards important phases of the

lunar cycle). However, there are also locations upon this planet, at

which the celestial cycles can be measured more accurately than at

others. For example, in Egypt, it was noticed that on the 23.5�

latitude, close to the Nabta stone circle c. 4,000 BC, that there

was no shadow during the equinoxes. This simple observation can be

seen to be a natural intellectual trigger for further astronomical

knowledge, and was most likely the reason for the construction of this

particular complex at the specific location

we find it.

Extending this line of thought to Europe, we find that

there are only two latitudes at which,

in some nights of the year, you get the full moon on the zenith. The

first is

38� 33′ 28″, the

location of the Evora complex (and the

oldest astronomically orientated stone circle in Europe), while the

other latitude is 51� 10' 42" N, that of

Stonehenge. Should we consider it

a coincidence that at these very two latitudes, we find two of the

largest, earliest and most prominent stone circles on the European arena.

The idea that Stonehenge was situated astronomically (or geodetically) is not one which

sits comfortably with historians as there is good evidence for use of

the site from at least 3,500 BC (in the nearby Cursus), not forgetting the stubborn presence of the four tree-posts, which date back

to Mesolithic period 7,000 BC. However, in

favour of its deliberate and specific placement is the fact that it is at

this latitude only the sun and the moon have their maximum setting points

at 90� to each other.

Perhaps it is through these astronomical facts we this we can begin to

understand the Avebury/Silbury complex better, for the latitude of

Avebury (Which sits exactly 1/4 of a degree of latitude north of

Stonehenge), also has a mathematical significance (and one which

should also not be ignored out of hand). Avebury is located on

latitude

51� 25'

40'', which is the result of 360 divided by 7 as

seen in the following expression.

(360� / 7

= 51.428 or 51� 25' 40")

We can see the

same type of Geodesy was applied to Egyptian structures (i.e.

Karnak/Thebes), which was the sacred centre of 'upper' Egypt was built

at latitude 25� 43' N, (360 / 14), and of course

Heliopolis, which the sacred centre of 'Lower' Egypt was built on the 30th

latitude. Sacred Temples built in upper Egypt are orientated to the

solstices while those built in lower' Egypt (the pyramids), were

orientated to the equinoxes.

Karnak/Thebes (360� /

14 = or 25� 43'), Heliopolis (360� / 12 = 30)

It is perhaps also

worth noting that while the exterior angle of the Great pyramid is the

same as the latitude of Silbury Hill, the exterior angle of Silbury is

simultaneously mirrored in the latitude of the Great pyramid.

Something which can be seen to follow through to other pyramids and

latitudes..

Returning to the

Orkneys complex, we find it also has a strong astronomical

significance.

It is at the

latitude of the Orkneys that the major lunar standstills north becomes

almost circumpolar, (neither rising nor setting - with the

effect that the moon 'rolls' along the horizon). Because the

Earth�s axial tilt has changed by nearly half a degree since the

majority of the stone circles were built, this effect is no longer

accurate and the latitude today would have to be 63� north for a lunar

standstill north to be truly circumpolar

(3),

while a truly circumpolar Moon would have been visible on the Orkneys

at around 3,500 BC. Once again, we are presented with a clear reason

for the presence of this concentration of astronomically profound

Megaliths on such a desolate island group.

The sites Almendres

stone circle near Evora shares an intimate connection with Stonehenge,

in that it is located on the correct latitude so that on certain

nights over an 18.6 year cycle, the full moon can be seen on the

zenith. The close proximity of the great Zambujeiro passage mound,

which is by far the largest in Iberia, and which ranks as one of the

best in all Europe, marks the region out as having a special

significance to the Neolithic builders. The close association between

astronomy and the megalithic structures is demonstrated by connections

both at sites, and between them.

Cromleque dos

Almendres: Apart from being orientated to mark the Equinoxes, a

line from the upper edge of the circle to the nearby Menhir dos

Almendres,

follows the same path as the winter solstice sun. It is also suggested that the number of stones in the

original circle (91) may have been used to measure the number of days

between solstices (182).

Zambujeiro passage

mound - The spectacular passage mound of Zambujeiro, the largest

in all Iberia, has unfortunately suffered the ravages of time, but in

doing so, the interior structure has been revealed in a unique way,

allowing us to witness the true vastness of the structure. The passage

has a slight curve and a stone pillar slightly blocking the entrance

to the inner chamber. Both of these features are seen in other

European passage mounds where they were used to highlight the sun on

the winter solstice. The passage is orientated

approx 20�

off true East (110�).

Both of the above sites, (Almendres and

Zambujeiro) are part of an alignment which terminates at the

Xarez stone 'quadrangle', near

Monsaraz. This alignment follows the path of the spring moon. It also

raises questions about the function of such stone 'Quadrangles'.

(More about the Almendres-Xarez

alignment) (More

about Stone Quadrangles)

A Geodetic Relationship between Complexes..?

Although the

complexes appear randomly situated, several are related by complete

units of degrees of latitude.

|

Geodetic

connections between complexes. |

| Maes Howe |

58�

59' 56" N, |

3� 11' 20" E. |

Positioned due to

Lunar phenomena (See above)

|

|

|

|

|

| Newgrange |

53�

41' 40" N |

6�

28' 30" W |

Inter-visible with

Tara Hill, (Sacred heart of Ireland) |

| Tara Hill |

53� 35' N,

|

6�

36' W |

(6�

N, 3.5�

W of Carnac),

(15� N, 1.5� E of Evora) |

|

|

|

|

| Avebury/Silbury |

51� 25' 40'' N |

01� 51'

6" W |

(Latitude 360/7),

(St. Michael's Ley) |

|

|

|

|

| Carnac |

47� 35' 52" N |

03� 3' 47" W |

(9� N, 5� E of Evora),

(6�

S, 3.5�

E Tara Hill) |

|

|

|

|

| Evora |

38� 33′ 28″ N |

08� 3′ 41″ W

|

(9� S and 5� W of Carnac),

(15� S, 1.5� W of Tara Hill) |

Note: Sites that show separated by units of 1�

(accurate within 3' of a degree

or 95%)

|

Additional Sites. |

| Callanish |

58�

12' 12" N |

6� 45' 25" W |

(7� N, 4� W

G'bury), (7� N, 5� W S'henge), (5�

N, 2.5�

W B.C.Ddu) |

| Bryn Celli Ddu |

53� 12' 30" N.

|

4�

14' 20" W |

(5�

S, 2.5�

E Callanish), (2�

N, 1.5�

E G'bury) |

| Arbor Low |

53� 10' N, |

01� 46' W |

(2�

N, 1�

E G'bury), (5�

S, 5�

E Callanish), (same lat, 2.5�

E B.C.Ddu) |

| Stonehenge |

51�

10' 42" N, |

01�

49.4' W. |

(0.25� S of Avebury), (7�

S, 5� E Callanish) |

| Glastonbury |

51� 09' N |

2� 45' W |

(7� S, 4� E Callanish), (2�

S, 1.5�

W B.C.Ddu), |

|

The Island of Malta

served as a prehistoric complex for Earth-mother worship for well over a

thousand years. The isolatory nature of the island has made it a 'Petrie

dish' of prehistoric life for researchers. Regardless of this

apparent isolation, the island retained a constant association with a

form of Earth-mother

worship, as reflected in the numerous female figurines and the

rounded, almost anthropomorphic shapes of the temples themselves.

The Island of Malta

served as a prehistoric complex for Earth-mother worship for well over a

thousand years. The isolatory nature of the island has made it a 'Petrie

dish' of prehistoric life for researchers. Regardless of this

apparent isolation, the island retained a constant association with a

form of Earth-mother

worship, as reflected in the numerous female figurines and the

rounded, almost anthropomorphic shapes of the temples themselves.