|

Location: Mainland

Orkneys, Scotland. |

Grid Reference:

59� 00' N. 3� 00' W. |

The Orkneys:

(Megalithic Complex).

The Orkneys:

(Megalithic Complex).

The Orkneys complex has been seen for a

long time as a separate cluster of megaliths. However, it is now realised

that several of the megalithic sites are connected, forming a prehistoric

ceremonial landscape.

The stark landscape of the Islands also offers a unique backdrop for these

beautifully constructed sites, against which they take on an ethereal

quality, as the builders must have been aware.

(Click here

for Orkneys map)

There are several

prominent megalithic sites on the Orkney Islands. The availability of

such good quality local stone gave these megaliths a unique

quality which still remains today. Until now there has been little solid

evidence for dating the sites. This year (2008), Renfew's 1973 trenches

were re-opened at Brodgar, and a series of samples have been sent for

radio-carbon dating (4).

We await the results.

Who were the builders

of the Orkneys megaliths?

It is suggested

that because the the two stone circles have henges that were dug

from the living rock, that the builders may have introduced this

technique from elsewhere, such as England where vast henges were

dug, but usually into soil.

The Neolithic

immigration of the Orkneys began around 3,500 BC.

There are

several features of the primary Orkneys megaliths which have

similarities to other Megalithic structures from further south

in Europe (i.e. Ireland, England, France), with all have

similarly orientated passage-mounds, Henges, Stone-circles

suggestive of astronomical observation. Also the structures

themselves show strong cultural similarities through art,

technique and design. At present, these people are commonly

referred to as the 'Beaker-people', or 'Boat people' from the

Neolithic period. A trend for migration along the western coast

of Atlantic Europe can be seen from southern to northern with

the Orkney complex representing the northerly most example of

socio-astro-religious civil-scale constructions.

Recent archaeology at the

'Ness' of Brodgar have revealed

that the Orkneys placement of the monuments into the landscape

shares similarities with the 'ritual' landscape at Stonehenge.

It has been proposed by archaeologist Mike Pearson that the

landscape represents the division between the world of the

living and the world of the dead.

Suggestions

that the Neolithic megalith builders were closely connected with

the Irish passage mound builders, for example can be seen

through the art, construction and preference for

orientation.

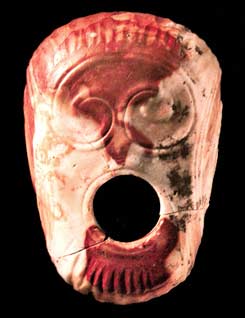

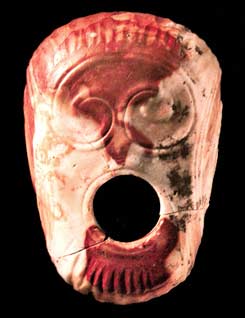

This beautiful mace-head (right), was

found at Knowth. The flint

itself comes from the Orkney

islands, which are by no means the nearest source of flint

to the Boyne valley. It is one of several clues that testify to

a cultural exchange between these two important megalithic

complexes, along with the style of art, exterior and interior

similarities in design of the passage mounds (Maes

Howe) and a strong astronomical theme underlying the

development of the structures.

(Prehistoric

Irish/Scottish/French connections).

|

Maes Howe Passage Mound:

Maes Howe was carefully constructed to allow the winter solstice sunlight

to enter the passage, entering the inner chamber for several minutes only

each year. The sun shines into the chamber for a few minutes each year before

it passes behind the Hill of Howe, re-appearing for another few

minutes before setting between the two hills.

Meas Howe should not be viewed as an

independent structure. It was an integral part of the

prehistoric landscape, as the photo above illustrates. The

whole area can be seen as an outdoor ceremonial arena, with

the ever-present Hills of Hoy in the background receiving

the midwinter sun and marking the new year.

(More about Maes

Howe)

|

|

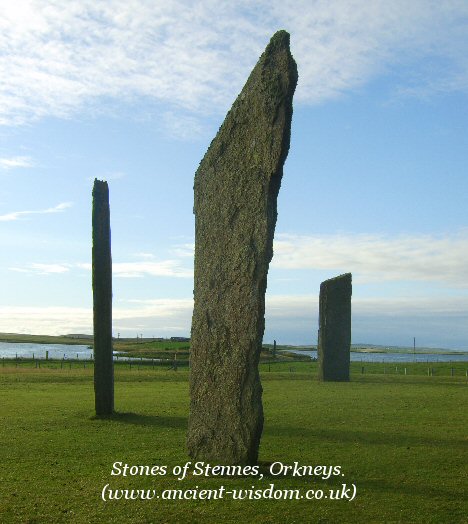

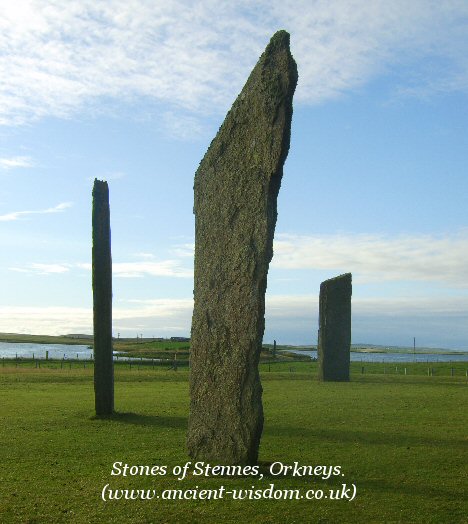

Stones of Stenness

View from Stennes across the artificial causeway.

Although it is

difficult to see, the 'Watch-stone', the 'Ness' of Brodgar and the Ring of Brodgar

are all visible in this photo.

(Watch-stone

between centre and right stones, Brodgar left of left-hand

stone)

There were once

two 'watch-stones' at the entrance to the causeway and

archaeologists are currently in the process of uncovering

the complex between across the causeway, believed to have

once been a 'ceremonial' walled complex separating the sites.

(More about the Stones of Stennes) |

|

The Ness of Brodgar.

This walled

enclosure is currently being revealed by archaeologists. It

separates the Stones of Stenness from the Ring of Brodgar making

it essential part of the landscape. It is now

realised that the site is composed of as many as 100 structures,

with several vast, complex, and beautifully constructed

buildings)

(More about the Ness

of Brodgar)

|

|

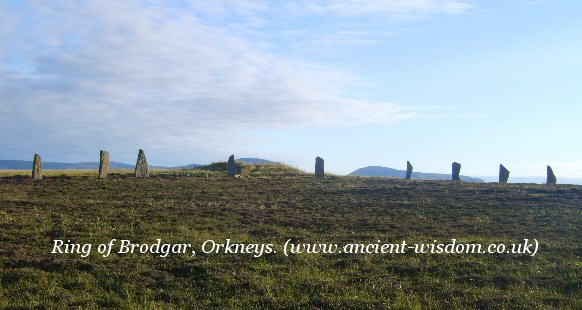

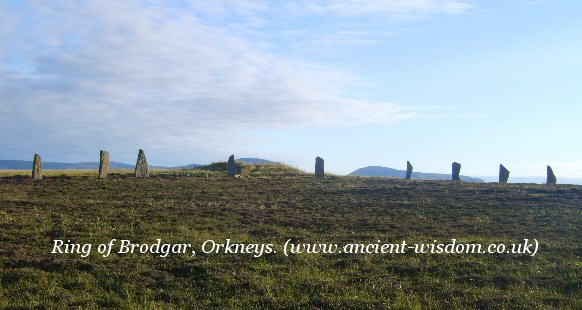

The Ring of Brodgar.

From the centre of this, the second largest circle in Britain, it can be seen how a mound was deliberately

built at the same place the sun set behinds the left-hand Hill of Hoy on the

winter solstice. This attempt to replicate the horizon can be seen in several

other megalithic sites in Scotland where it is also generally associated with

astronomical observation.

(More about the Ring

of Brodgar)

|

|

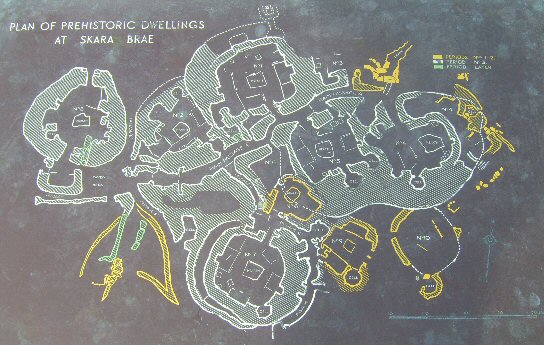

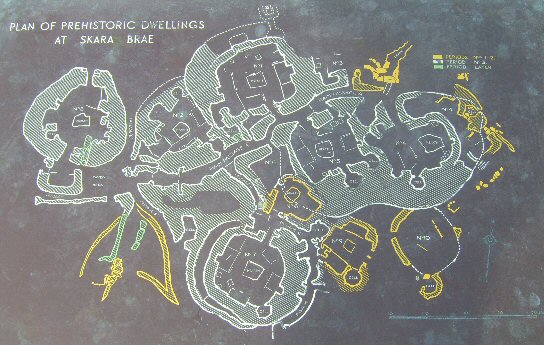

Skara Brae: A Priestly centre?

Skara Brae was built by the coast, in a beautiful

bay facing the setting sun. The 'village' lies in line with the great circles of

Bookam, Brodgar and Stennes which are now realised to have been part of a

ceremonial route, through what must have seemed a most sacred landscape through

Neolithic eyes. The position of Skara Brae at the end of such a significant

grouping of monuments combined with discoveries inside offers the possibility

that the structures (and inhabitants) may have even been a part of the

ceremonial process.

The overall layout of Skara Brae has several

design factors which suggest a specialised function, such as 'workshops',

a room lockable only from the outside..?? and the discovery of several hoards of

precious items hidden in the walls of the chambers (such as 2,400 inscribed

beads and pendants in one find alone).

(More about Skara Brae)

|

|

Archaeoastronomy on the Orkneys: |

At the latitude of the Orkneys the

major lunar standstills north becomes almost

circumpolar, (neither rising nor setting - with the effect that

the moon 'rolls' along the horizon). Because the Earth�s axial

tilt has changed by nearly half a degree since the majority of the

stone circles were built, this effect is no longer accurate and the

latitude today would have to be 63� north for a lunar standstill

north to be truly circumpolar

(5), while a truly circumpolar

Moon would have been visible on the Orkneys at around 3,500 BC.

Maes Howe:

The entrance to the Maes-Howe

passage-mound is orientated towards the setting winter solstice sun

behind the prominent Hills of Hoy in the distance. The chamber was

placed so that for several days before and after the winter

solstice, the sunlight flashes directly into the passage not once,

but twice, with a break of several minutes between each

illumination.

The passage is aligned facing

Southwest, facing Ward Hill. For 20 days before the solstice and for 20 days

after the solstice, the sun shines into the chamber twice a day. Every 8

years Venus causes a double flash of light to enter the chamber. This last

happened in 1996 and will happen again in 2004. �At around 2.35 p.m. on the

winter solstice, the sun shines on the back of the chamber for 17 minutes,

and then sets at 3.20 p.m. At 5.00 p.m. the light of Venus enters the first

slot, lighting the chamber, and then at 5.15 p.m. it sets behind Ward Hill.

But 15 minutes after its first setting, Venus reappears beyond Ward Hill,

and the light enters the chamber for a further two minutes, before setting

for a second and last time�. (16).

A series of measurements and

alignments have been taken which connect the Maes Howe Tumulus with

the Ring of Brodgar revealing a common unit of measurement.

In a direction 60� south from

the centre of the Ring of Brodgar at a distance of 63 chains is the

'Watchstone' (18ft high), 42 to 43 chains further on in the same

line is the 'Barnstone', (15 ft high). At the same distance of 42 or

43 chains to the north-east of the Barnstone is the tumulus of Maes

Howe.

The Ring of Brodgar is a

stone-circle which originally consisted of 60 equally spaced

megaliths. The Stones of Stennes was originally a stone-circle

consisting of 12 equally spaced stones. The numbers of stones used

for the circles is suggestive of base-6 mathematics, the same base

upon which all time and space was measured in the ancient

middle-east

Burl makes note of the 'mistaken

coincidence' in connection with this fact. He says of it:

'From Brodgar, where there was once 60

stones, to the Stripple stones with a probable thirty, the builders may have

counted in multiples of six.

Stennes had twelve. The inner and outer

rings at Balfarg have been computed at twenty-four and twelve respectively.

Twenty-four has been suggested for Cairnpappel, thirty-six for

Arbor Low, and

the same number for the devils quoits'.

(3)

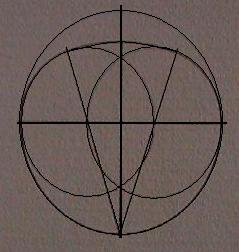

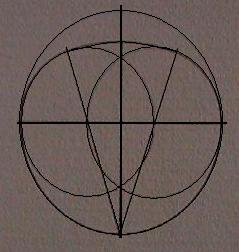

Thom radically suggested that geometry was used in the

design of certain prehistoric sites. He surveyed hundreds of European

megaliths and concluded that fundamental mathematic principles, based upon a

common unit of measurement (which he called the

megalithic yard),

had been applied in the design of certain

sites. As the megalithic tradition in Europe can be traced back to at least

4,000 BC, if not earlier still, his work is still not accepted by most

archaeologists, although such a strong presence of geometry should not be

ignored, as is clearly suggests that the design of many sacred sites seems

to have been based on a sophisticated philosophy of sacred science such as

was taught centuries later by the Pythagorean school.

As Professor Thom observes in his book

Megalithic Sites in Britain

(1967):

�It

is remarkable that one thousand years before the earliest mathematicians

of classical Greece, people in these islands not only had a practical

knowledge of geometry and were capable of setting out elaborate

geometrical designs but could also set out ellipses based on the

Pythagorean triangles.�

(More about prehistoric geometry)

|

Comparisons with other European Complexes: |

There are several noticeable similarities between

the megalithic structures of the Orkneys, and those found at other

contemporary European complexes. In particular, there are some distinct

examples of art and design which appear common to the Irish passage

mounds, such as those of the Boyne Valley. The discovery at Knowth of a

stone axe-head from the Orkneys confirms this relationship.

There are several fundamental similarities

between the Orkneys 'ceremonial' complex and other contemporary

complexes along the western Atlantic coast. In particular, the Orkneys

provides a perfect example of the two essential components of many

complexes; a prominent mound and circle in close proximity to each

other. The mound, which can be seen as the 'primal hill', is often

realised in the form of a passage mound although regional variations

exist such as at Avebury/Silbury.

On the Orkneys, the

monuments were constructed so as to merge with the landscape, in such a

way that the stones compliment their backgrounds. The same sensitivity

is seen at other megalithic sites, but nowhere is it realised quite so

well as on the Orkneys. The creation of these large-scale civil

constructions represents a form of higher communication between

ourselves and the universe we live in. Their intimate connection with

the living landscape into which we place them connects us to the earth,

and their invariable orientation towards Solar and Lunar events brings

us into time, with the visibly beating heart of the universe.

Other Similarities:

Both

Gavr'inis in France and

Newgrange

in Ireland were built at around the same time as Orkneys

monuments (c. 3,100 BC).

Along with Maes Howe, they all have

their passages aligned to mark the winter solstice. (Close to the Moons

eastern major standstill). This single alignment offers the potential

for the realisation of the Metonic cycle.

(More about

Prehistoric Astronomy)

As well as astronomical orientation,

the Maes Howe passage mound has several specific construction

features which are common with other European passage mounds, such

as their rounded shape, lowered passageway with raised internal

chambers, cruciform chambers, stone libation bowls and an absence of

contemporary funerary remains.

The theme of a Mound and Circle

together is also repeated at Neolithic Complexes across Europe.

(Similarities Between European

Passage Mounds)

The interior floor-level of both

Gavr'inis and

Newgrange were raised towards the

centres. At Newgrange, the upwards-sloping passage narrows the beam of

light into a thin strip. In fact, the only light that would have

originally been able to enter the internal chambers would have come

through the 'light-box', above the

passage entrance.

Light-boxes are a megalithic construction feature

that have so far only been recorded at three (possibly four) sites in

the UK, with two in Ireland (Newgrange

and

Carrowkeel

- see below) both having the

same design, and the other two on the

Orkneys in Scotland.

This particular connection is very specific.

(More

about Light-boxes)

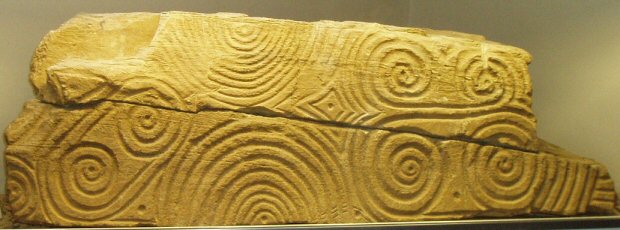

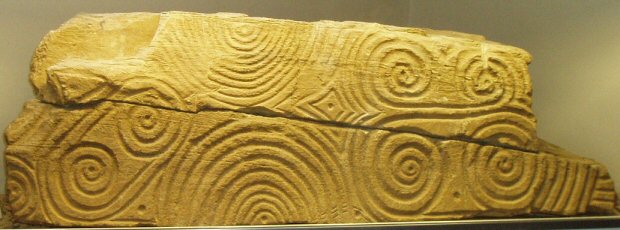

Spiral Art.

The 'Westray Stone', from Pierowall

(left). The Eday Manse stone, Isle of Eday.

(right).

Bugibba, Malta, (Left),

Newgrange,

Ireland (right).

(More

about Spirals)

(Stenness)

(Brodgar) (Maes

Howe) (Ness of Brodgar)

(Skara Brae)

(Neolithic Complexes: Similarities between European Sites)

(Sacred Landscapes)

(Other Scottish Sites)

|