|

Passage Mounds:

(Form and function).

Passage Mounds:

(Form and function).

|

Featured Items.

Passage mounds rank among the largest

prehistoric structures left by the megalithic builders. They are

strongly associated with astronomy, and share constructional

features with both dolmens and Pyramids.

|

There are several substantial passage-mounds across western Europe, some of

which can have only been built with the support of a large-scale

organisation of skills, labour, materials etc. The fact that the majority of

the largest European passage-mounds were built at the same period of

prehistory (c. 3,500 - 3,000 BC), combined with similar construction

principles, art, design and orientation of passages, leads one to look at

the development of these structures at this particular period of

prehistory as representing the result of an establish and structured

society.

|

Passage Mounds - Form and Function. |

By definition, a passage-mound is... 'A mound - with a passage in it...'.

The passages of all the

significant European mounds are invariably orientated so as to mark significant

celestial events (such as the equinoxes, solstices, and lunar minor and major

stand-stills), allowing light to enter the interior of the mound at fixed

moments of the year only.

Passage mounds are generally considered to have originated from

the basic circle or henge monuments, such as at Brynn

Celli Ddu, in Wales. However, there are components in the design of the

mound which can be seen in other megalithic structures. The principle of

orientating a structure to allow sunlight to enter it at selected

times of the year is echoed in the construction of Egyptian monuments.

The internal masonry that

composes the passage and chamber of European passage mounds also shares

a strong similarity to that of dolmens, which themselves range from a simple

dolmen ( chamber)

to a dolmen including a passage (Allee

Couverte).

This picture is of the Zambujeiro passage-mound in Portugal, which has

had a large part of the mound removed revealing the passage masonry, showing

strong similarities with the Allees-couverte of France .

What's in a name?

For a long time, passage-mounds, along with several

other ancient structures, were assumed to be 'funerary' structures. For this

reason, these structures were termed

funerary mounds, passage graves

etc, but human remains, when there were any have almost invariably revealed

themselves to be from a secondary use. It is no longer possible to ignore the

fact that there is also a strong astronomical influence in the design of the

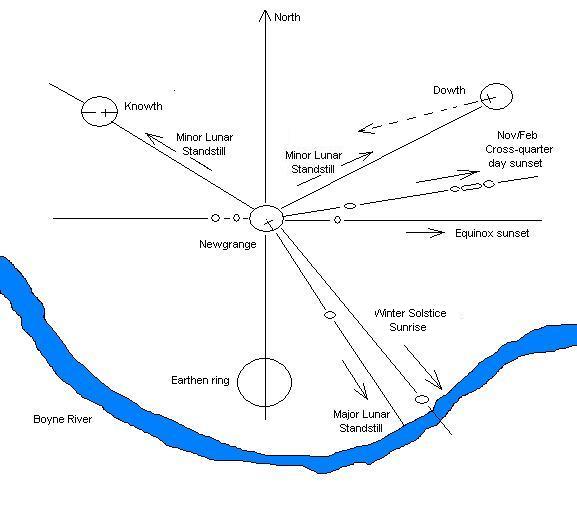

particular structures. In the Boyne valley, Ireland - the passage-mounds and their

surrounding structures have been shown to jointly offer an accurate means of

calculating the most significant moments in both the lunar and solar cycles.

|

Tara Hill, Ireland.

The 'Mound of hostages' - on the Hill of Tara

in Ireland is a legendary sacred site (The Sacred Heart of Ireland).

Along with many other passage mounds, it is orientated to allow the passage

of sunlight to 'penetrate' its body only once each year. The connection

between the female Earth-goddess and the male Solar-God is obvious.

(More about Tara

Hill)

|

There is little argument to

the notion that, as the menhir is to the male, so the passage

mound is to female. The association is well documented and can be

seen around the ancient world. But to what extent is the

association with passage mounds and the female form valid? - What

purposes did they serve, beyond a possible representation of the

earth-mother-goddess. The oracle centres of ancient Greece were

traditionally frequented by females called 'Sybils' who were

associated with serpents and the underworld...

(More about the Oracles)

|

The Logistics of Passage mound Building.

The building of such large passage mounds as those seen

at the Boyne valley, Gavr'inis, Maes-Howe, Zambujeiro etc, would have been no

easy endeavour, with man-hours estimated in the thousands for each

structure.

In addition, the variety of skills, organisation and levels of energy required to accurately

achieve such constructions, suggests the presence of a highly organised society.

We are told by the guides at

Newgrange that this structure alone took an estimated

50-60 years to build, (the length of

two

average Neolithic lifetimes), effectively ruling it out as a 'funerary'

structure....

|

When were they built :

The earliest passage

mounds are recorded in France, Ireland c. 4,700 - 4,600 BC. At

this early period of time all the classic elements of the passage

mound were already in place. At Kercado in France, the passage mound

was built orientated towards the midwinter sunrise (6), while in

Ireland, they appeared only 100 years.

Recent research

in France has revealed that several of the passage-mounds in the

Carnac region were constructed around 3,300 BC, by people

who used and absorbed the megaliths from existing monuments made

by a previous megalithic culture

(over a thousand years earlier), into the megalithic structures which we see today.

Their early appearance in southern Europe and consequent

re-introduction at 3,300 BC in France, Wales, and 3,200-3,000 BC

in Ireland and Scotland offers a suggestion of coastal migration

northwards.

Passage-mounds and Stone Circles:

The primal 'Mound of Creation'.

There were

several types of prehistoric 'mound' to be seen on the prehistoric landscape.

Many of them are simple 'cairn's' or 'barrow-mounds' and are solely

associated with funerary rituals. However, there are also several other larger

mounds which appear to have served other functions, including the observation

of astronomical events.

The

numerous 'Beacon' Hill's in Britain have been mentioned above, and tradition and

observation shows that they served the same function as passage-mounds but to a larger

audience through the lighting of beacon fires in lines on hill tops across

the open landscape. This too can be seen as a multi-functional act, both

demonstrating a physical connection with the cycles of the cosmos through

aligned landscape features, at the same time as connecting observers.

The

Boyne-valley passage mounds were each

orientated so that the sunlight reached along the passages and into the

central chambers at very specific moments of the solar and lunar cycles. In addition, The same is true of

Maes-Howe on the Orkneys,

Gavr'inis in France,

Bryn-Celli-Ddu in Wales and

Zambujeiro in Portugal. All of these

passage mounds were constructed according to a set of basic astronomical

requirements, which at the same time as enabling the builders to measure the

solar and lunar cycles accurately, physically connected them to the

beating heart of their

universe.

It is proposed that

these mounds were a symbolic representation of the primal 'Mound of

Creation', rising from a watery mythological past. The Maes Howe

mound above is connected to the ceremonial landscape of the Orkneys

through the close proximity of the Stennes circle, and within sight

of that, the larger Brodgar circle, a combination which appears to

have a common thread at several other western European megalithic

complexes: (Avebury/Silbury Hill, Gavr'inis-Er-Lannic, Zambujeiro-Almendres,

Ggantija/Xaghra). Regional variation on this theme has resulted in

several combinations: In Ireland, Tara Hill shows the same features

combined in the same ceremonial setting, only with the mound in the

centre of the circle, Newgrange mound was built over an existing

Stone circle, and Avebury has two circles built within it. This

association of a prominent mound and associated circle/s can be seen

to be one of the basic features of several of the (contemporary

Neolithic) western-European ceremonial arenas. There are several

other more specific similarities which suggest a contact along the

Atlantic coastline of Europe between these civil-scale ritual

complexes.

(Similarities between Neolithic

Western-European Complexes)

(The

Mound Builders of North America)

|

Similarities Between European Passage-Mounds: |

While the outsides of many

passage-mounds have suffered from the fancies of the restoration

team, the insides have remained relatively untouched, and it is here

that we find several structural and artistic similarities between the European

passage-mounds. The following examples include some of the

largest and well known passage mounds in Europe.

Similarities in Design:

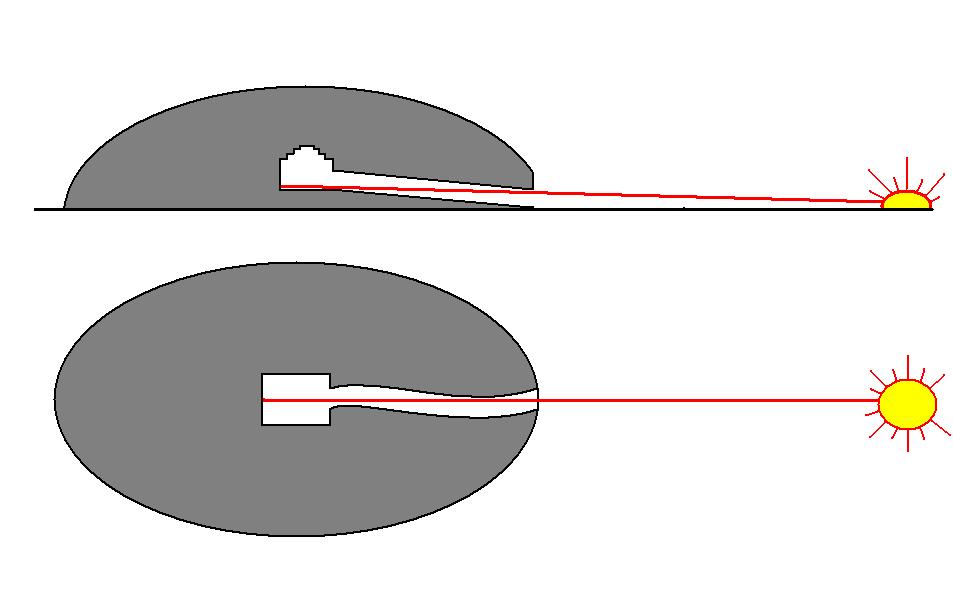

Raised internal chambers: Both the Newgrange and

Gavr'inis passage-mounds have artificially raised internal chambers.

In Newgrange, this elevation of the chamber reduces the entry of light

into the central chamber as the following diagram illustrates.

At Newgrange, the light-box

is used along with other construction features (such as the

passage narrowing and undulating along it length and a

subtle increase in altitude towards the centre), which

combine to focus the rays of the

sun along the passage into a small, narrow beam of light,

which is visible for only a few minutes on a few days

around the winter solstice. As well as illustrating the

astronomical nature of the structure, the inclusion of such

a specific set of designs highlights the importance of accuracy to the builders.

|

'Light-Boxes':

Light-Boxes

are a construction feature specific to European passage-mounds.

The incorporation of light boxes into megaliths is one of the

few direct proofs of the link between megaliths and astronomy, as

their purpose was the manipulation of light into the passage mounds at

certain times of the year only. In Egypt, the earliest pyramids all contain

'polar-shafts', and on Malta, the 'Temples' were orientated towards the

solstices and equinoxes. In Britain, all the known passage-mounds

containing light-boxes were also aligned with solar events, (i.e. the

equinoxes or solstice)

-

Newgrange

- Ireland, (Winter Solstice, Lunar standstill)

-

Crantit

Tomb, Orkneys - (Start and end of winter..?)

Carrowkeel

(Cairn-G), ( Possibly

Cairn-H),

Ireland, (Summer and winter solstice, Lunar standstill)

Maes Howe - Orkneys, (Winter

solstice).

Bryn Celli Ddu - Anglesey, (Summer

solstice, Lunar standstill)

(More about Light-boxes)

|

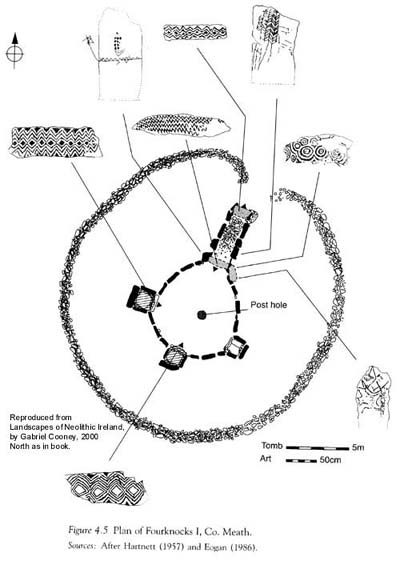

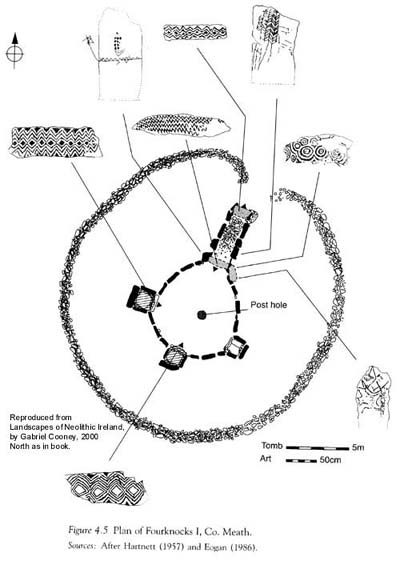

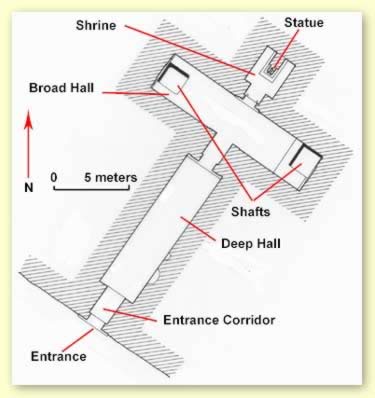

Newgrange, Knowth, Dowth, Fourknocks and Maes-Howe all have cruciform chambers

inside

(And

the

internal layout of the Maltese temples also show strong

similarities).

The exact function/purpose of the cruciform design is still unknown,

but there are some common threads which may offer a clue as to

their original purpose.

European Cruciform chambers are frequently

associated with astronomical orientation.They are distinguished by a long

passage leading to a central chamber with a corbelled roof. From this,

burial chambers extend in three directions, giving the overall

impression in plan of a cross shape layout. Some examples have further

sub-chambers leading off the three original chambers. The network of

chambers is covered by a cairn and lined outside with kerb-stones.

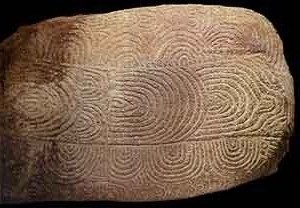

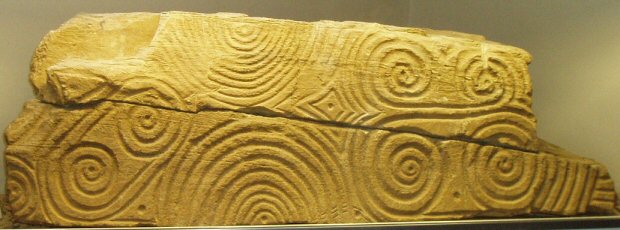

A common trait is megalithic art

carved into the stones of the chambers' walls and roofs. Abstract

designs were favoured, especially spirals and zig-zags.

Examples are

Newgrange ,

Knowth,

Dowth and Fourknocks

(amongst many) in Ireland,

Maes howe in

Orkney, 'La Hougue Bie' on Jersey and Barclodiad-y-Gawres in Anglesey,

and the Maltese temples.

Newgrange (left), with three stone bowls, one in

each recess, Maes Howe (right).

Fourknocks, Ireland, with cruciform chamber and

'crossed' lintel-stones.

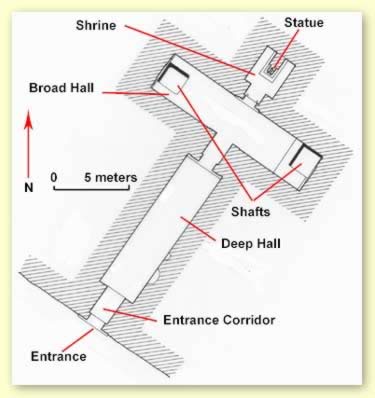

Egyptian Cruciform Chambers.

The

tomb of Ahmoset (left); 'Fanbearer on the King's Right Hand',

'Steward of the Estate of Akhetaten' and 'Royal Scribe' at

Akhetaten' during the Amarna Period, was also cruciform in

shape. It is interesting to note that here too a bowl was present.

'The shrine opening from the very back of the

broad hall on the center axis of the tomb was undecorated, though a

seated statue of the tomb owner was cared at is back. However, this

is now badly mutilated. A libation basin was cut into the floor in

front of the statue'.

(Ref:

http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/Ahmoset.htm )

The same cruciform symbolism is seen around the ancient world,

where it is often associated with the 'World-Tree' or the Sun.

Palenque, Mexico (left), Celtic cross (right).

The Maltese temples are believed to have been

originally covered over, which would have rendered them with

essentially the same exterior design as the other other European

passage mounds.

The Maltese temples, whilst retaining a essentially

internal cruciform shape, are rounded in the same way as the

earth-mother figurines found across the island. It has been suggested

that this interior design can also been seen at other prehistoric

constructions such as Skara Brae, on the Orkneys and over 60 Neolithic

houses across the British Isles.

(5)

(More about the

Earth-mother-earth)

It has been noted that the cruciform chambers of several

large, prominent passage mounds contain large, stone-cut 'offering'-bowls or

'libation-bowls'.

Above left and right - Hal

Tarxien, Malta.

Knowth (left), Newgrange

(centre) with one in each recess, and Dowth

(right).

The bowls at the Boyne valley (above) were found to have

funerary deposits in them, although it is not clear if that was what their

original purpose was. In the case of the Dowth bowl, it has been shown from

its dimensions that the passage (and therefore the mound), had to have been

built around it. The engravings on both the Newgrange and Knowth bowls

suggest that they are contemporary too.

(More about the Boyne-valley

complex)

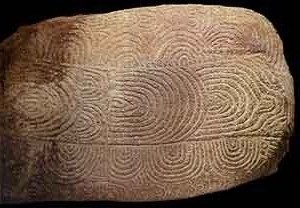

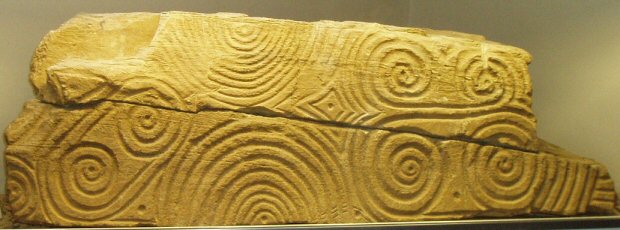

Spiral Art and Passage-mounds:

The Kerbstones from Newgrange K-52 (left) and

Gavr'inis, France, right share several

symbolic designs.

Stone SE4 at Knowth has a series of

crescents running down the side, a design similar to that found on the

rear stone inside Le Table des

Marchands' passage mound, (nearby and contemporary with

Gavr'inis).

It has also been noted that there are several distinct similarities between

the art of the

Boyne Valley complex and the Orkneys

complex as

the following pictures illustrate.

Newgrange kerbstone (left), and the 'Westray'

stone, Orkneys (right).

Similar Art can be seen on Malta. The

contemporary images of the prehistoric Maltese temples show them as

being covered over, which, when combined their internal cruciform

design and the fact that they were generally orientated to the same

moments of the year reveals a set of common themes with the western

European passage-mounds.

|

Passage-mounds and Astronomy: |

The

following table

supports the idea that there is an intimate relationship between passage-mounds and

the astronomical orientation of their

passages.

|

Name of Mound |

Orientation |

| |

|

|

Carrowkeel,

Ireland (Cairn G). |

Summer solstice sun, Winter solstice moon. |

|

Dowth, Ireland |

Cross-quarter

day sunset, and minor lunar standstill. |

|

Fourknocks, Ireland |

17� east of

true north (Unknown). |

|

Knocknarea, Ireland |

Unknown. |

|

Knowth, Ireland. |

Lunar minor standstill, Equinoxial. |

|

Loughcrew, Ireland |

Various orientations. |

|

Newgrange, Ireland |

Winter solstice sunrise. |

| |

|

|

'La Hougue Bie', Jersey. |

Equinoxes. |

|

Barclodiad-y-Gawres, Anglesey. |

(Coming Soon). |

| |

|

|

Gavrinis, France |

Winter solstice sunrise. |

|

Kerkado, France |

Midwinter sunrise. |

|

La Table des Marchands, France |

Summer solstice sunrise |

| |

|

|

Maes Howe, Scotland |

Winter solstice sunset, Venus |

| |

|

|

Brynn Celli Ddu, Wales |

Winter-solstice, Venus. |

| |

|

|

Commenda da Igreja, Portugal |

Pleiades rising. (Marks the start of

the agricultural year) |

|

Zambujeiro, Portugal |

Spring full moon 110�

- Alignment to Xarez. |

| |

|

|

Cueva

de Menga, Spain. |

Passage mounds orientated towards nearby 'Head'. |

| |

|

At 4,700 BC, The Kercado

passage-mound is one of the earliest examples in Europe. It was

carefully orientated towards the midwinter sunrise.

The Boyne-Valley passage-mounds.

The Boyne Valley complex have been shown to have been

built so as to be orientated and aligned amongst each other so as to

mark several important solar and lunar events. Combined with the

inter-visibility of structures at

Loughcrew and Tara hill, both of

which were important megalithic sites in their own right, and both of

which also contain astronomical markers, and we are able to begin to see

that there is no doubt that astronomy was important to the builders of

the large Irish passage-mounds of 3,200 BC. It is suggested that this

network of inter-visible sites would have operated like a giant

'calendar' for the inhabitants at the time. (1)

(More about Astronomy and the

Megaliths)

- (More about

the Boyne-valley complex)

|

Examples of Passage-Mounds: |

Examples of Passage mounds.

The passage mound structure varies from region

to region, whilst maintaining similarities in design, construction,

and art and presumably purpose.

|

French Passage-mounds:

Research in France has

revealed more than one building phase of passage-mounds in the Carnac region.

The Neolithic builders of 3,300 BC

absorbed the monuments from an earlier megalithic culture into their

own structures (from over a thousand years before).

Kercado passage mound, Carnac,

France. At 4,700 BC, this is one of the earliest in Europe.

The capstones from

Gavr'inis (left),

Er-Grah, and

La Table des Marchands

(right), have all been shown to be parts of a earlier, single

monolith. The construction phase for these passage mounds is

dated at around 3,300 BC.

(More about the Carnac

complex)

|

|

The

Irish passage mounds: Ireland has the

highest concentration of passage mounds, and they have been shown to

serve a specific function, namely that between them, they functioned

provided the locals with an accurate calendar of all the major solar

and lunar events throughout the year. (1) The

Irish passage mounds: Ireland has the

highest concentration of passage mounds, and they have been shown to

serve a specific function, namely that between them, they functioned

provided the locals with an accurate calendar of all the major solar

and lunar events throughout the year. (1)

The Irish passage mounds from the

Boyne valley region, were built at around 3,200 BC

(2), the same time as the French were building

theirs.

(Boyne-Valley complex)

|

Portuguese

passage-mounds: There are several passage mounds in

Portugal ranging from full sized, 50m diameter mound of

Zambujeiro to the more frequent but smaller mounds such as the

Orca mounds by the Mondego river.

The Portuguese passage

mounds present themselves as a unique hybrid of both dolmen

and passage-mound, with several of them having never been

fully covered.

Although there are several

different variations on the design of the Portuguese mounds,

they have a style that remains unique to themselves which is

that the stones supporting the capstones (invariably between 7

and 9), are placed with the front stones seemingly resting on

the larger stones at the rear of the chamber. This style of

construction is not seen elsewhere in northern Europe where

the stones are placed upright independently of each other.

Another noticeable fact with

many of the Portuguese dolmens and Passage-mounds is that a

great many of them have the top-half of the stone on the N-E

of the chamber missing. (Pers. Obs.)

(Prehistoric Portugal) |

|

Spanish

Passage Mounds: Spain has several

prominent passage mounds, including arguably the largest one

in Europe. Spanish

Passage Mounds: Spain has several

prominent passage mounds, including arguably the largest one

in Europe.

The

Cueva de Menga complex include three

substantial passage mounds.

Cueva de Menga is considered to be one of the largest

such structures in Europe. It is twenty-five metres deep, five metres

wide and four metres high, and was built with thirty-two megaliths, the

largest weighing about 180 tonnes.

The entrance to the dolmen faces the

anthropomorphic Pena de los Enamorados in the distance.

(More

about Cueva da Menga complex)

|

Gallery of Passage Mounds: Quick Links.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

La Table des Marchands, France |

Kerkado, France |

Gavrinis, France |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Hougue Bie, Jersey. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Brynn Celli Ddu, Wales |

Cueva

de Menga, Spain |

Maes Howe, Scotland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anta da Arcainha, Portugal. |

Tapadao, Portugal |

Orca da Lapa, Portugal |

Anta Grande do Igreja da Commenda, Portugal |

Zambujeiro, Portugal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mound of Hostages, Ireland |

Knocknarea, Ireland |

Fourknocks, Ireland |

Newgrange, Ireland |

Loughcrew, Ireland |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Dowth, Ireland |

Carrowkeel |

Knowth, Ireland. |

|

|

Spanish

Passage Mounds: Spain has several

prominent passage mounds, including arguably the largest one

in Europe.

Spanish

Passage Mounds: Spain has several

prominent passage mounds, including arguably the largest one

in Europe.