|

Light-boxes: Light-boxes:

Light-boxes are an

exclusively Neolithic design feature employed so as to restrict the

entrance of light into a chamber or passage.

This particular construction feature has so far

only been recorded at four (possibly five) sites in the

Britain, with the two in Ireland (Newgrange and

Carrowkeel)

both having the same design, two on the

Orkneys (Maes Howe and

Crantit) in Scotland and one in

Wales (Brynn-Celli-Ddu).

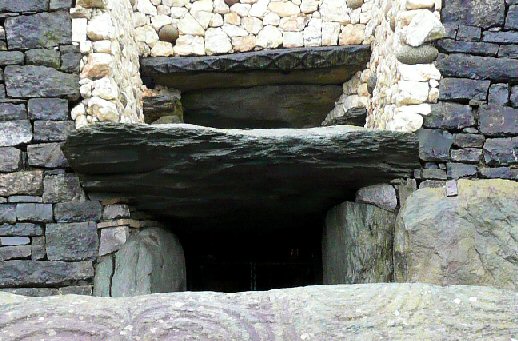

Newgrange at the Boyne Valley (right), possesses the finest known example of a

'Light-box'.

The incorporation of light boxes

into megaliths is one of the few direct proofs of the link between megaliths

and astronomy, as their purpose was the manipulation of light into the

passage mounds at certain times of the year only. In Egypt, the earliest pyramids all contain 'polar-shafts',

on Malta, the 'Temples' orientated towards the solstices and equinoxes and in

Britain, all the known passage-mounds containing light-boxes were

also aligned with solar events, (i.e. the equinoxes or solstice)

At present there are only

four (possibly five), known examples of 'light-boxes', all

in European megalithic

structures (passage-mounds). Their design permits a

focused beam of

light from prominent celestial objects such as the sun and moon, to

enter the chamber at specific times of their cycles. The

most famous of these is at

Newgrange in Ireland, where the light-box allows the

suns rays to pass along the passage into the heart of the

mound on the winter-solstice sunrise, (and possibly, one of

the major lunar stand-stills - to be confirmed)...

-

Newgrange

- Ireland, (Winter Solstice, Lunar standstill)

-

Crantit Tomb, Orkneys - (start

and end of winter..?)

Carrowkeel

- Ireland, (Summer and winter solstice, Lunar standstill)

Maes Howe - Orkneys, (Winter solstice).

Bryn Celli Ddu - Anglesey, (Summer

solstice, Lunar standstill)

At Newgrange, the light-box

is used along with other construction features (such as the

passage narrowing and undulating along it length and a

subtle increase in altitude towards the centre), which

combine to focus the rays of the

sun along the passage into a small, narrow beam of light,

which is visible for only a few minutes on a few days

around the winter solstice. As well as illustrating the

astronomical nature of the structure, the inclusion of such

a specific set of designs highlights the importance of accuracy to the builders.

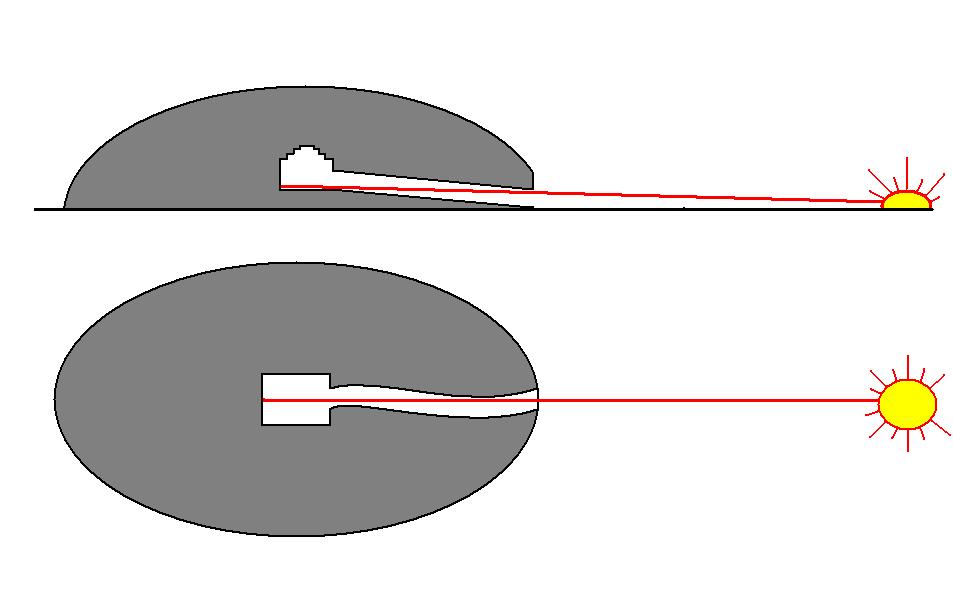

Image illustrating the

design of the Newgrange passage and chamber (Not to Scale)

|

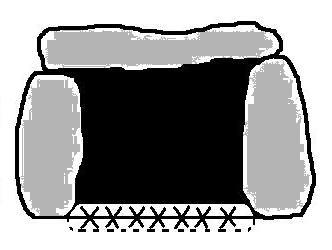

The Crossed/Lozenge lintel-stones.

The passage-mound at Gavr'inis has a

specific feature in common with at least

one other passage mound in Ireland. They

both have a stone with a series of 8 (9 - see below), crosses/lozenges on its face in the

entrance or passage.

This feature has been found at both

Newgrange (over the light-box),

and at nearby Four-knocks. We

already know that Newgrange has been dated at 3,200 B

(2), which, when combined with

the similar orientation and passage art, lends itself to the idea

that they may all be contemporary structures.

Newgrange, East-rear lintel inside the chamber.

Gavrinis 'Sill-stone' in floor, left.

Fourknocks, having three

crossed lintels, right.

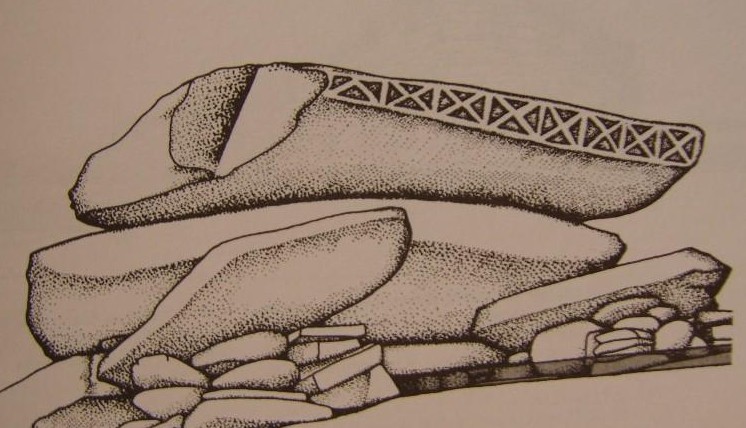

The drawing on the right was made

before the reconstruction of the Newgrange mound. It suggests that

the lintel-stone at Newgrange may have had 9 crosses on it rather

than the 8 usually quoted. If this is the case, then the stone would

be an almost exact match for the stone in the

Gavr'inis passage mound

(which also has 9 crosses), now in the floor of the passage (where

only the tops of the crosses are now visible as a series of 'V's).

The Gavrinis 'Sill-stone' lies across the passage floor in a

style similar to the passage mounds in Ireland (such as those at

Carrowkeel), where 'sill-stones'

are found on the floor, apparently symbolically dividing the internal structure.

It has been noted that this specific design-feature is found on the floors of

ocean-going ships.

The passage-mound at

Four-knocks has three similar lintel stones,

with two in position over the side chambers, and a third at the

entrance. The significance of this design can only be guessed at,

and the appearance of a similar stone in the contemporary Gavr'inis

passage mound lends further weight to the argument for a close

cultural contact between the Irish and French Neolithic passage

mound builders.

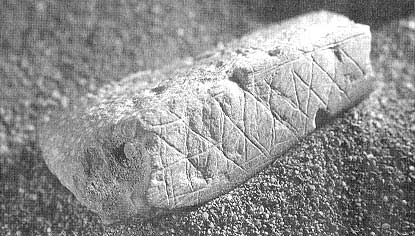

This ochre stone was found in a cave by the sea in

Africa with the same markings on it. It is dated at approx. 70,000

BC. (Full

article)

|

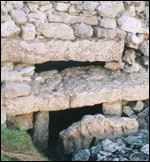

Newgrange (left), and

Carrowkeel (right).

Carrowkeel: A second Irish light-box has been recently discovered through

the research of Martin Byrne, who showed that a Neolithic

tomb at

Carrowkeel was oriented

to the most northerly point the setting Moon reaches on the

horizon, an event that only happens every 18.6 years at

midwinter. The report suggested that the lunar association

had been missed until now because it is only very

occasionally illuminated by sunlight or moonlight....

Several mounds at

Carrowkeel have features

that suggest the possibility of light-boxes:

The Carrowkeel light-box was designed to capture the light of the

setting sun at summer Solstice, and the light of the setting moon at the

winter solstice and Lunar Extremes.

Cairns H (Right) and D have long box-like kists. Cairns G and K have

cruciform chambers and

double-lintelled entrances.

This offers the possibility that other passage mounds at Carrowkeel will one

day be identified as having 'light-boxes' in their design.

Cairn B has the most commanding position of all the tombs. Within a

kerbed cairn 22.5 metres in diameter and 5 metres high is an accessible,

fairly-crude pentagonal chamber with two sill-stones at either

end of a passage.

Maes Howe: Orkneys:

The light box in the Maes Howe passage mound is

different in design to the Irish ones, in that it is a

'moveable' stone, which was built into the original design

of the passage. The function of the stone is intrinsically

the same. The stone sits in a pre-designed cavity in

the corridor, and can be moved at will (The guide said that

it had 'rocking' properties). It is triangular in shape, and

its design is such that when it is in a 'closed' position,

it restricts the entry of light along the passage (whilst

leaving a gap at the top for a small amount of light

to enter).

The light of the

setting solstice sun was restricted by the closing of a 'portal stone', placed into the side of the passage. In this way, at the

right moment, the stone could be closed across the passage, and the

light would only pass over the top (as at Newgrange). The

same design feature is also present in the entrances of the three sub-chambers, each of

which also had a blocking-stone which closes most of the hole, but not all of

it. (These stones now lay on the floor in front of the holes).

Inside the cruciform

chamber of Maes Howe there are three other smaller chambers

built into the walls, each of which has its own

smaller version of these partial 'blocking' stones lying on

the floor in front of it. Their position makes it fairly

obvious that they were each once in the holes that they sit

in front of, and their smaller size and triangular shape

repeats the design of the 'blocking' stone in the corridor.

(More about Maes Howe)

The Crantit tomb, Orkneys:

A

possible

light-box

has been

found in the Orkneys, in the underground Crantit tomb after a tractor

disturbed a series of flat stones that turned out to be

5,000 year old

roof slabs. It was noticed that one of these roof-stones had

a notch

cut into it which would allow a ray of sunlight to penetrate the

tomb in October and again in February (at the beginning and

the end of winter) when the Sun would have thrown a shaft of

light along the length of the tomb.

Strange carvings were found on the upright stone pillar

that holds up the roof. "If you look closely you can see

geometric patterns and symbols carved into the rock," Dr

Ballin Smith said. And in respect to the 'light-box' we are

told that:

The south-east

facing section of the cairn appeared to have a notch in

the wall. Although it looked like no more than a

broken stone, it seemed that the "notch" had been

put there deliberately.

The first investigation revealed that the cairn had

not actually been covered by a mound, but had instead been

dug into the ground. This seemed to indicate that it was

never meant to be visible from the surface.

This fact marked the Crantit cairn (and the 'light-box') as being hugely unusual.

However, the fact that it was both sealed, underground and

dubiously orientated casts a doubt on the validity of the

'light-box' as it would only have functioned following the

removal of clay and

roof-stones, which is not consistent with the design of the

two other light-boxes in Ireland.

The following photo's are

Before and After photos from Crantit following

the second official investigation of the site.

(More about the Crantit tomb,

Orkneys)

Note: At the latitude of the Orkneys the major lunar

standstills north becomes almost circumpolar, (neither rising

nor setting - with the effect that the moon 'rolls' along the horizon).

Because the Earth�s axial tilt has changed by nearly half a degree since

the majority of the stone circles were built, this effect is no longer

accurate and the latitude today would have to be 63� north for a lunar

standstill north to be truly circumpolar (10), while a truly circumpolar

Moon would have been visible on the Orkneys at around 3,500 BC.

(More about the Orkney

Islands)

|

The Bryn Celli Ddu 'Light

Pillar'. |

The Bryn

Celli Ddu passage mound does not have a 'light-box' per se,

but it does appear to have a sophisticated means of measuring the year

incorporated into its design, by restricting the entry of light into the passage

at certain times. The design of the entrance and passage acts along with a pillar in the chamber,

as a

declinometer by casting a dagger of light on the

pillar, which changes height throughout the year. The light

which enters the chamber is focused so that it falls almost

exclusively on the pillar in question.

At Bryn Celli Ddu, the passage-mound

was designed in such a way so as that the light of the sun at

relevant times of the year would penetrate the chamber and cause a

beam of light to be cast on a 'Declination Gauge' made by the tall,

cylindrical pillar placed at the back of the hexagonal chamber.

The changing altitude of the sun over

the year causes the light of the sun that reaches the inside of the

chamber to move up and down the pillar over the year. Notches have

been found which support this theory.

|

The positioning of the stones at the entrance and along the

passage restrict the light into a narrow beam which can be

seen to move up and down the pillar over the year. |

|

(More about Bryn Celli Ddu)

|

The 'Light-Tube' at Monte Alban, Mexico. |

The so called 'Zenith Tube' found in Building 'P' in the centre of

the ceremonial centre at Monte Alban acts in essentially the same

way as the European 'Light-boxes', allowing a beam of light to pass

through a pre-designed 'chimney' built into the structure. These

'Light-tubes' were designed for measuring the moments when the sun

passed overhead twice each year on its azimuth.

At the bottom of the light-tube is a large viewing chamber which the

sun would illuminate twice each year. The top of the shaft had a

small, precisely fitted shaft running directly east which it is

believed to have acted as a predictor-gauge for the 'light-tube'.

( More

about the Monte Alban 'Light-tubes')

The deliberate precision with which

these passages were constructed is extended outwards to the

strangest structure at Monte Alban, nearby and also in the centre of

the grand plaza is building 'J' or 'The Observatory', with its

irregular angled walls and carved stellae, this building is both

orientated along its axis towards building 'P', and to the northeast

to where the bright star Capella was seen to rise in the

processional era of 275 B.C

The fact that both these structures

occupy a noticeably central position in the ceremonial mountain

citadel, sitting at the centre of the Oaxaca Valley,

which was once inhabited by onwards of 35,000 people making it the

second largest pre-Columbian city in Meso-America, and second only

to

Teotihuacan in the north,

demonstrates their importance to the Zapotec builders. One or two

other examples of 'light-tubes' are known to exist at other Zapotec

sites.

(More

about Monte Alban)

|