|

Location:

Oaxaca Valley,

Mexico. |

Grid Reference:

17� 02' N. 96� 42' W. |

Monte

Alb�n:

(Zapotec Capital).

Monte

Alb�n:

(Zapotec Capital).

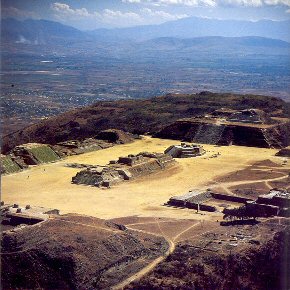

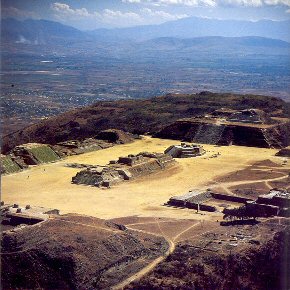

The levelled hilltop on

Monte Alban is the heart of the second largest ceremonial site in

Mesoamerica, and is exceeded in size only by Teotihuac�n. It is believed to have supported up to 35,000 people in its heyday,

revealing it as an important part of the pre-Columbian American landscape.

The site contains some of the

earliest undeciphered hieroglyphs found in all of Mesoamerica.

Although this was one of the most enduring of all the civilizations of

Mexico (lasting from about 500 B.C. to 800 AD), it experienced a sudden

and rapid decline at the same time as the collapse of other pre-Columbian cities elsewhere in

Mexico.

(Click here for map of the site)

|

Monte Alban: (White Mountain): |

The previous names for the city were the Mixtec name "Sahandevul"

which means "At the Foot of the Sky", and another variation which is

derived from the older Zapotecan language, "Danibaan" or Sacred

Mountain".

Monte Alban is

visible from anywhere in the central part of the Valley of Oaxaca

Believed to have been built around 600 BC, the huge complex of ceremonial

buildings on top of Monte Alban mountain has some of the most oddly shaped

structures of the ancient world. Not only was much of the stone brought up

from the valley floor, so was all the water, as the site has no visible

natural source. Blanton's survey of the site

(1), suggests that the

Monte Alb�n hill itself appear to have been uninhabited prior to 500 BC although the valley is

now believed to have been continuously occupied since

2000 BC

There

are a large number of carved stone monuments at

Monte Alban. The earliest examples are the so-called "Danzantes" (dancers),

which represent naked men in contorted and twisted poses, some of them

genitally mutilated. The 19th century notion that they depict dancers is

now largely discredited, and these monuments, dating to the earliest

period of occupation at the site (Monte Alb�n I), clearly represent

tortured, sacrificed war prisoners, some identified by name (see below

for more).

In its

heyday, Monte Alban was the one of the greatest Zapotec 'holy' cities, with

a population of over 30,000 . It is estimated that only about 10% of the site has yet been uncovered.

|

San Jose Mogote. -

(The Forerunner to Monte Alban)

The earliest Zapotec city was San Jose el Mogote, also in the Oaxaca

Valley and founded about 1600-1400 BC; it was abandoned around 500 BC,

when the capital city of Monte Alb�n was founded at the beginning of the

Zapotec heyday. The Zapotecs built their new capital city in the middle

of the valley of Oaxaca, between three populous valley arms and at the

top of this steep hill. Building a city away from major population

centres is called 'disembedded capital' by some archaeologists, and

Monte Alban is one of very few disembedded capitals known in the ancient

world.

San Jos� Mogote is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the

Zapotec, a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in the region of

what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca. A forerunner to the

better-known Zapotec site of Monte Alb�n, San Jos� Mogote was the

largest and most important settlement in the Valley of Oaxaca during

the Early and Middle Formative periods (ca. 1500-500 BCE) of

Mesoamerican cultural development.(2)

Situated in the fertile bottomlands of the Etla arm of the Valley

of Oaxaca, the site is located two blocks from the community museum

in the present-day village of San Jos� Mogote, which is about 7.5

miles (12 kilometres) northwest of the city of Oaxaca (Evans

2004:122).

San Jos� Mogote is considered to be the oldest permanent

agricultural villages in the Oaxaca Valley and probably the first

settlement in the area to use pottery. It has also "...produced

Mexico�s oldest known defensive palisades and ceremonial buildings

(1300 B.C.), early use of adobe (850 B.C.), the first evidence of

Zapotec hieroglyphic writing (600 B.C.), and early examples of

architectural terracing, craft specialization, and irrigation

(1150-850 B.C.)..." (3) |

Chronology: Monte Alb�n.

-

Monte Alban Period 1 (650

BC to 200 BC) is known to have had stone buildings, permanent temples,

priests, and an organized religion.

-

Monte Alban Period 2 (200

BC to 1 AD) is characterized by an

influx of a group of people from Chiapas or Guatemala who were smaller

in numbers, but introduced changes as they merged with the resident

population.

-

Between Monte Alban Period 2 (200 BC to 1 AD)

and 3A (100 AD to

400 AD) there is evidence of influence from and trade with Teotihuacan

to the North.

-

Between Monte Alban Period 3A (100 AD to 400 AD)

and 3B (400 AD To

700 AD) the vast majority of the city was reconstructed.

-

Monte Alban Period 4 (800 AD To Spaniards) is the beginning of the

decline of Monte Alban as a major power base in the area.

-

Monte Alban Period 5 reflects the influence of the Mixtec

occupation.

|

Olmecs at the Oaxaca valley.?

It is known that the history of the region started around 4000 years

ago when a village-dwelling people of unknown origin (suggested by some

to have been Olmec colonies) moved into the Oaxaca valleys. Then, around

500 BC (1500 years later) a new people (the Zapotecans) moved into the

region. One of these groups then began the monumental task of levelling

the top of a 1,600 meter high mountain that intersects and divides three

valley, and built Monte Alban with a maze of subterranean passage ways,

rooms, drainage and water storage systems.

Archaeologists may still argue over who founded Monte Alban (in spite

of the oldest reliefs which are clearly Olmec), but what they do agree

on is that in the following centuries, the Zapotecans (the new people to

move into the area) were responsible for the distinct architectural

style and rise to power of Monte Alban (which coincides with the exact

time period that the powerful, war-like Olmec civilization went into

full-scale decline).

It is difficult to believe that any group other than the long

established governing power which controlled the population and

resources of the valleys below would be able to complete the task of

building Monte Alban, or that they would allow a new group of people to

move right into the middle of their territory and take up a dominant

military position on the strategic high ground controlling three

valleys.

Los Danzantes (Building of the Dancers)

is the main highlight of the west side of the plaza.

The oldest known structure at Monte Alban is known as The Gallery of the

Dancers. The glyphs depict naked warriors, ejaculation, childbirth,

dwarfism, captives, the sick, genitally mutilated and the dead with

contorted body positions (like dancers). These pictures are the

oldest artefacts found here and date back to the origins of the city itself.

The distinct artistic style, and the features of the people with round

mongoloid facial features and beards is pure Olmec. The meanings of

these symbols, people, positions, or historical context is open to

interpretation.

One of the strongest characteristics of Monte Alb�n

is the large number of carved stone monuments one encounters throughout

the plaza. The earliest examples, the so-called "Danzantes"

(literally, dancers), were found mostly in the vicinity of Building L. The

19th century notion that they depict dancers is now largely discredited,

and these monuments, dating to the earliest period of occupation at the

site (Monte Alb�n I), clearly represent tortured, sacrificed war

prisoners, some identified by name, and may depict leaders of competing

centres and villages captured by Monte Alb�n (Marcus and Flannery 1996;

Blanton et al. 1996).

Over 300 �Danzantes� stones have been recorded to

date, and some of the better preserved ones can be viewed at the

site's museum.

These images are clearly of Olmec origin, and similar

contorted figures can be seen at the Olmec capital of

La Venta, which

was occupied from 1200 BC until 400 BC. |

In the centre of the plaza (and presumably of

extreme importance) are two constructions, the largest (in

three sections) was a temple system that included tunnels to other

temples on the site. The second building is the only one not aligned

with the cardinal points and is thought to have been used for astronomy,

hence its name 'The Observatory'. It has several interesting

architectural features.

Building 'J': The Observatory.

A different type of carved stones is found on the nearby Building J

in the centre of the Main Plaza, a building characterized by an unusual

arrow-like shape and an orientation that differs from most other

structures at the site. Inserted within the building walls are over 40

large carved slabs dating to Monte Alb�n II and depicting place-names,

occasionally accompanied by additional writing and in many cases

characterized by upside-down heads. Alfonso Caso was the first to

identify these stones as "conquest slabs", likely listing places the

Monte Alb�n elites claimed to have conquered and/or controlled. Some of

the places listed on Building J slabs have been tentatively identified,

and in one case (the Ca�ada de Cuicatl�n region in northern Oaxaca)

Zapotec conquest has been confirmed through archaeological survey and

excavations (Redmond 1983; Spencer 1982).

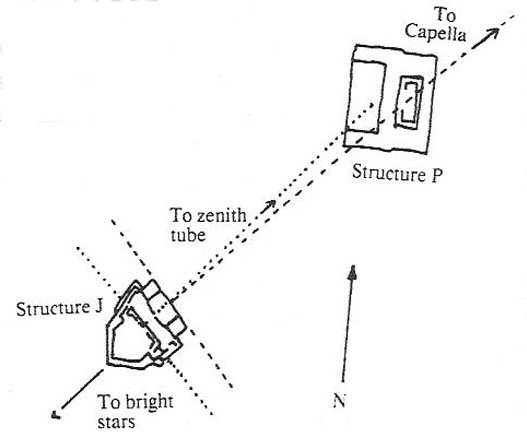

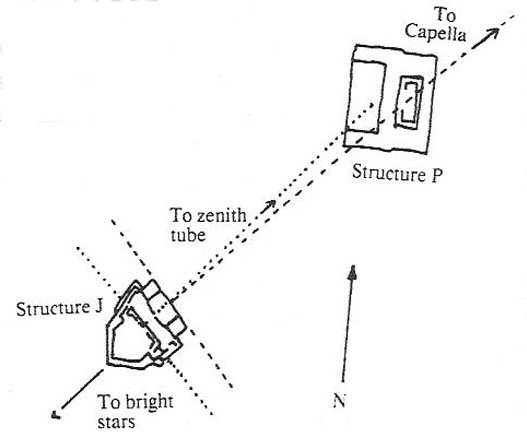

Building J, is interpreted by some scholars as an astronomical

observatory.

(Photo Credits:

sacredsites.com)

The archaeo-astronomer Anthony Aveni has shown how the building's front doorway is precisely

aligned with the point where the bright star Capella (the sixth

brightest in the sky) would have first appeared in the dawn sky each

year, on the same day that the sun reached its first of two

annual zenith days over Monte Alban, on each of which it casts no shadow

at mid-day. The front stairway of J is aligned in turn with Structure P

(on the eastern side of the plaza), which has a unique vertical shaft

leading down into a chamber down which the sun would have shone with no

shadow on that same day. Crossed-stick symbols found on Structure J lend

further support to the importance of astronomical sighting-stick

observations from this position. Moreover, the asymmetric plan of

Structure J turns out to be precisely aligned with the point to the west

where 5 of the 25 brightest stars in the sky, including the Southern

Cross, first rise above the horizon.

Most structures at Monte Alban are oriented 4

degrees to 8 degrees east of north.

The perpendicular to Structure J's baseline shoots

through what was an opening or doorway in Structure P points northeast

to where the bright star Capella was seen to rise in the processional

era of 275 B.C. During this time Capella made its first reappearance in

the predawn sky (its heliacal rise) on May 8, which is the first solar

zenith passage date at the latitude of Monte Alban. Solar zenith

passages (when the sun passes through the zenith at high noon) were

important indicators of the zenith centre. Solar zenith passages occur

only within the Tropics, that is between latitudes 23.5 degrees S and

23.5 degrees N. Amazingly platform Structure B through which the Capella

observations were sighted, houses Monte Alban's famous zenith tube. This

vertical tube leads into an underground chamber where zenith passage

measurements of the sun and stars could be made. Zenith tubes have been

found at other sites, such as Xochicalco in Central Mexico.

(Article on the Monte Alban Zenith-tube)

(Light-Boxes)

(Archaeoastronomy)

|

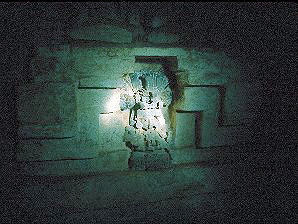

The Tombs.

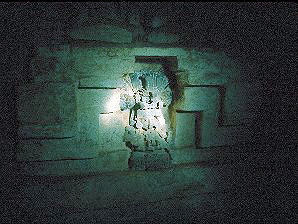

There have been over 200 tombs discovered at

Monte Alban.

Inside Tomb '104'.

It is interesting to note that in some cases a

rock wheel was used to roll across the entrance to the tomb to seal

it against intruders. A practice used in the Middle East during the

time of Christ.

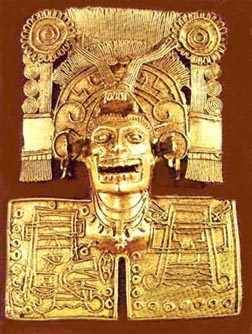

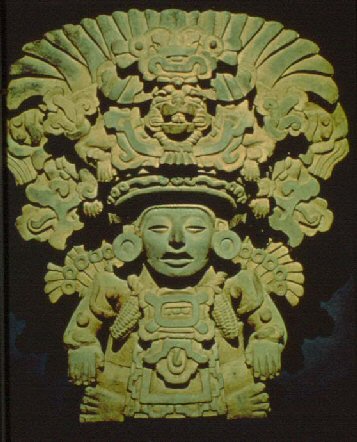

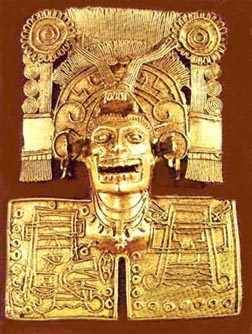

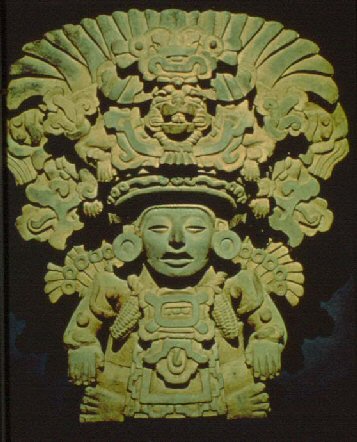

(Left) Gold pendant from tomb dating to the beginning of the 1400s. The pendent

represents Mictllanteuhtli, the 'Lord of Death', recognizable by his

fleshless jaws. (Right) Funerary Urn.

|

(Other

Mexican sites) (Archaeoastronomy)

(Pre-Columbian

Americas Homepage)

|