|

Location:

Mainland Orkneys, Scotland. |

Grid Reference:

58� 59' 56" N, 3� 11' 20" E. |

Maes Howe:

(Passage Mound).

Maes Howe:

(Passage Mound).

The largest passage-mound in

Scotland and one of the finest in Europe, Maes Howe is a small but

particularly elegantly designed structure. It is distinctly different from

other Orkneys 'cairns'

The passage is orientated

towards the setting mid-winter sun (behind the Hills of Hoy), and a

blocking-stone left deliberately in the passage wall which can be opened and

closed, controlled the entry of sunlight into the chamber.

(Map

of Orkneys Islands)

The site is

in state care, and the opening hours are restricted, especially in

winter.

�Maes Hwyr� -

Celtic for �The field of the

evening after the sun has set�.

(16).

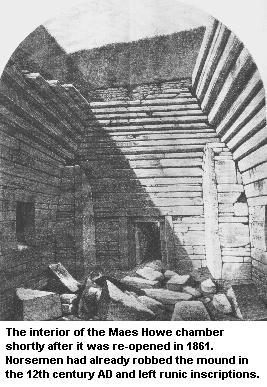

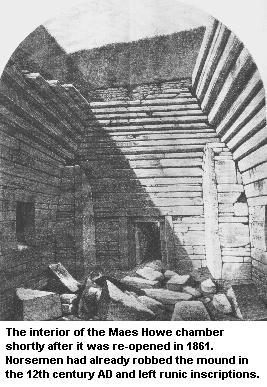

Evidence from various excavations

over the years has produced limited information. The passage and chamber

were cleared of debris in 1861, when a fragment of human skull was found in

one of the cells, along with some possible horse bones and teeth. Two

trenches were cut into the north-east and south east areas of the ditch and

mound in 1954-1955. Another cutting was made in the ditch and platform in

1973-1974, which showed that the surrounding ditch had originally been 2

metres deep. Evidence from various excavations

over the years has produced limited information. The passage and chamber

were cleared of debris in 1861, when a fragment of human skull was found in

one of the cells, along with some possible horse bones and teeth. Two

trenches were cut into the north-east and south east areas of the ditch and

mound in 1954-1955. Another cutting was made in the ditch and platform in

1973-1974, which showed that the surrounding ditch had originally been 2

metres deep.

Maeshowe was broken into from the top

by a party of Vikings in the 12th century, and they left over twenty sets of

runic inscriptions carved on the walls of the chamber to record their

exploits, as well as a carved lion and a serpent.

As the original contents of the tomb are

unknown to us, it is very difficult to speculate on rituals carried out at

the site. The fact that the entrance faces SW suggests that the builders of

Maes Howe had an interest in the winter sunset. At mid-winter, light from

the setting sun streams through down the passage to illuminate the inner

chamber.

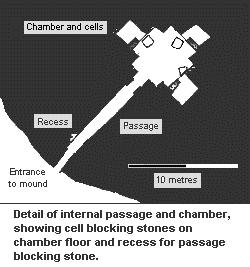

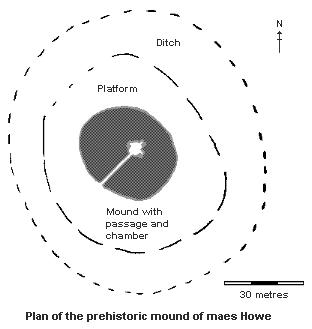

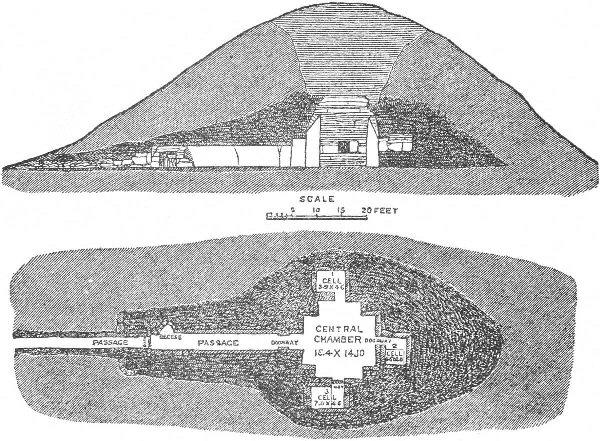

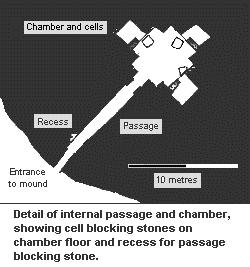

Schematic Plan of Maes Howe.

The Structure:

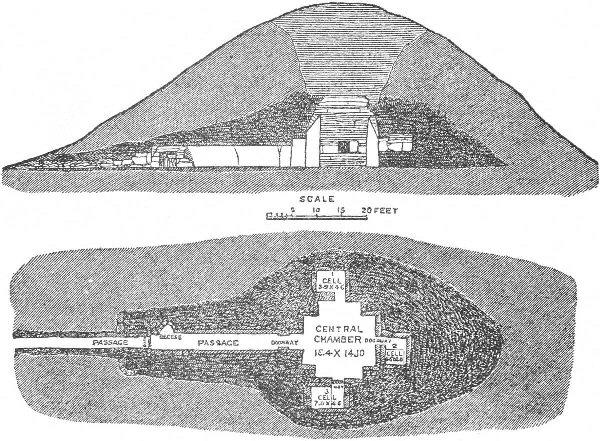

The mound is about 7.3 m (24 ft) high and

35 m (115 ft) in diameter, and a long passage (11 m/36 ft) leads to a tall

chamber 4.6 m (15 ft) square, deep in the mound. In one wall is the doorway,

but each of the other three walls contains a square hole nearly 1 m (3 ft)

above the ground. These open out into small chambers which once may have

contained burials. The quality of the dry-stone masonry is superb: no mortar

was used and some of the slabs still fit so well together that a knife blade

cannot be inserted between them. It has been estimated that the building of

Maes Howe, including the quarrying and transportation, could have taken

almost 39.000 man-hours The mound is about 7.3 m (24 ft) high and

35 m (115 ft) in diameter, and a long passage (11 m/36 ft) leads to a tall

chamber 4.6 m (15 ft) square, deep in the mound. In one wall is the doorway,

but each of the other three walls contains a square hole nearly 1 m (3 ft)

above the ground. These open out into small chambers which once may have

contained burials. The quality of the dry-stone masonry is superb: no mortar

was used and some of the slabs still fit so well together that a knife blade

cannot be inserted between them. It has been estimated that the building of

Maes Howe, including the quarrying and transportation, could have taken

almost 39.000 man-hours

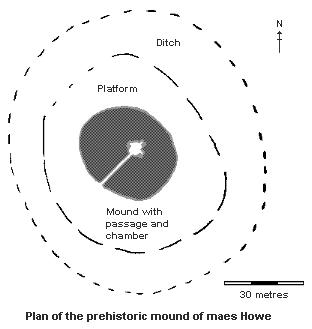

The tunnel-mound is placed centrally within a circular ditch and bank of

about 150 metres in diameter. The bank does not seem to be a true henge and

it has been suggested that it is the remnants of the flat, circular, clay

platform on which the mound stands. Radiocarbon dating for the bank and flat

platform show it to be far older than the tunnel mound, dating from 3,930 BC.

Whilst the structure itself dates from around 2,820 BC

(16), 3,100 BC (1),

2,800 BC (2). The chamber is

constructed with close fitting blocks whose surfaces have been chiselled

flat or round according to purpose. They are accurately plumbed to the

vertical, some being over 5 metres long and weighing up to three tons. The

main passage had a triangular stone block which could be used to seal it.

When the chamber was entered from the top by the Vikings in the 9th

or 10th century BC, the left inscriptions saying that they found

it empty. (16).

This famous monument consists of a

turf-covered mound over 7 metres high and 35 metres across, set on a level

platform which is surrounded by an original ditch. (The wall outside the

ditch is modern). Most of the mound beneath the covering of grass consists

of clay and stones.

The largest of these huge slabs are estimated to weigh around 30 tons

(4).

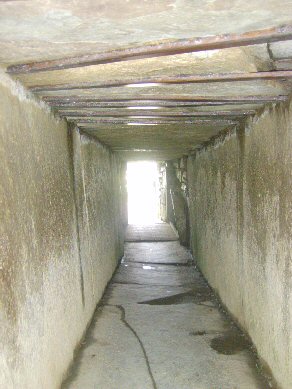

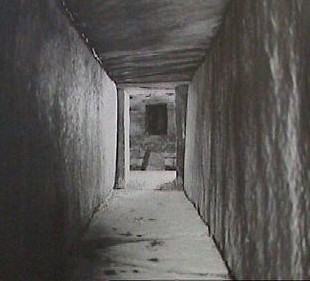

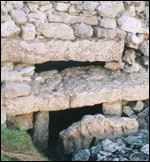

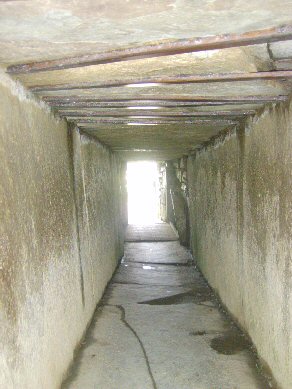

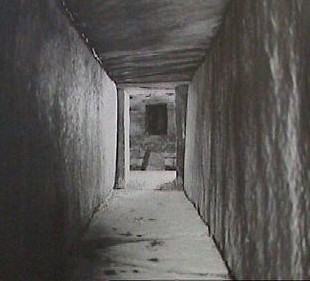

An entrance on the south-west side of

the mound leads into a stone-built passage which is 1.4 metres high, and

just under a metre wide. This passage runs straight inwards for over nine

metres, and leads to a relatively high and spacious chamber in the middle of

the mound measuring 4.5 x 4.5 metres. Vertical walls to head height are

topped by sandstone blocks to create a corbelled vault. Each

corner of the chamber has a buttress which serves to support the roofing.

There

are three recesses or cells in the chamber walls, set at just above waist

height. A large stone lies on the floor in front of each of the cells, and

these are likely to have been used as blocking. The stones for the passage

and chamber have been carefully selected and dressed, and fitted together

with care and precision.

|

The Cruciform Chamber.

The cruciform

chamber in the centre of the mound is vaulted by a corbelled roof,

and has three small sub-chambers leading from it. The cruciform

chamber in the centre of the mound is vaulted by a corbelled roof,

and has three small sub-chambers leading from it.

Each of these sub-chambers would have originally been covered by large

blocking stones, which now lie before them on the ground. It is noticeable

that the same design was used on the main entrance to the passage of the

chamber itself.

Cruciform chambers are found in several other passage-mounds in Europe, and

other megalithic structures around the ancient (and modern) world. Their

function to the builders is unknown exactly, but the association with

passage mounds and astronomy may offer a clue. It is noticeable that large

flattened bowls are also common in passage mounds with cruciform chambers (Knowth,

Dowth

Newgrange)

(More about the cruciform

chambers)

|

Archaeo-astronomy: The entrance

to the Maes-Howe passage-mound is orientated towards the setting winter

solstice sun behind the prominent Hills of Hoy in the distance. The

chamber was placed so that for several days before and after the winter

solstice, the sunlight flashes directly into the passage not once, but

twice, with a break of several minutes between each illumination.

The passage is aligned

facing Southwest, facing Ward Hill. For 20 days before the solstice and for

20 days after the solstice, the sun shines into the chamber twice a day.

Every 8 years Venus causes a double flash of light to enter the chamber.

This last happened in 1996 and will happen again in 2004.

�At around 2.35

p.m. on the winter solstice, the sun shines on the back of the

chamber for 17 minutes, and then sets at 3.20 p.m. At 5.00 p.m. the

light of Venus enters the first slot, lighting the chamber, and then

at 5.15 p.m. it sets behind Ward Hill. But 15 minutes after its

first setting, Venus reappears beyond Ward Hill, and the light

enters the chamber for a further two minutes, before setting for a

second and last time�.

(16).

The

passage faces south-west, towards the position of the setting sun between

the hills of Hoy (see above)so that the beam of sunlight strikes the back wall of the chamber.

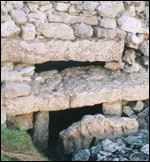

Just inside the entrance to the

passage on the left side there is a recess built into the passage wall. This

recess holds a large stone, which was found in the passage during the

excavations of 1861. This stone may have been used by the builders of

Maes howe to block the front of the passage. The recess suggests that the

blocking and unblocking of the mound could be carried out at will. The stone

fits the width of the passage exactly, but leaves a strip above open to a

height of 50cm. This feature is commonly referred to in connection to the

light-box above the

passage in the Neolithic mound of

Newgrange

in Co. Meath, which allows the light

into the chamber at sunrise on midwinter's day.

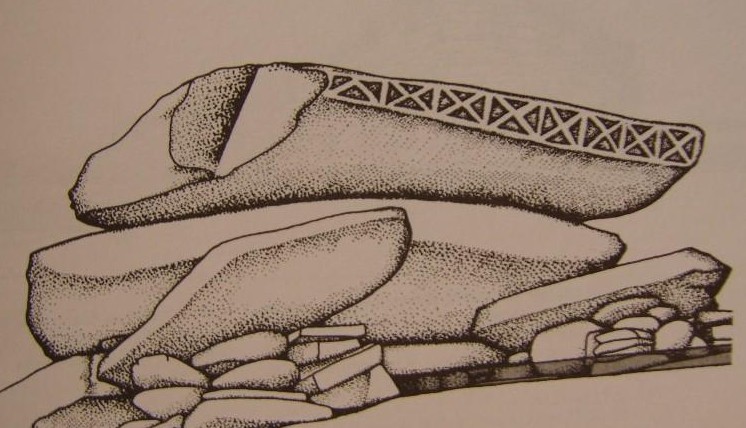

Light-boxes are a megalithic construction feature

that have so far only been recorded at three (possibly four) sites

in the UK, with the two in Ireland (Newgrange and

Carrowkeel

- below)

both having the same design, and the other two on the

Orkneys (Maes Howe and Crantit) in Scotland.

Newgrange (left), and

Carrowkeel (right)

All of these sites have been shown to have been

deliberately constructed so

as to allow the rays of the sun (and/or moon) into the interior of

the passages for very specific time periods only. One of the stones

from the light-box at Newgrange (right) has a particular design on

it which can be found at two other passage mounds:

Gavr'inis in France, and

Fourknocks in Ireland.

At Maes Howe, the light of the

setting solstice sun was restricted by the closing of a 'portal stone', placed into the side of the passage. In this way,

it is speculated that at the

right moment, the stone could be closed across the passage, and the

light would only pass over the top (as at Newgrange). The

same design feature is also present in the entrances of the three sub-chambers, each of

which also had a blocking-stone which closes most of the hole, but not all of

it. (These stones now lay on the floor in front of the holes).

This particular astronomical feature is similar to 'light-boxes'

found in other passage mounds in Ireland and Wales (Newgrange,

Carrowkeel,

Bryn Celli Ddu). A similar

feature is believed to have been found on the Orkneys at the

recently destroyed/restored Crantit

Tomb.

In contrast to the current theory above, Garnham

(3)

mentions that in 1861, the drawing by Gibb showed drop in the

passage roof such that only if the stone was removed would a shaft of

light pass down the passage. This is due to a reconstruction of the

passage which altered its original shape. He Says of it:

'Very long slabs are used for the floor, ceiling and

walls. These were laid on edge rather than flat and coused as in the

chamber, which enhances the sense of vast size. The enormous length

(12m) of the passage, it narrowness (0.7m) and low height (0.7m,

but reconstructed to 1.1m).....At the entrance there are

recesses to accommodate a blocking stone. This stone, 0.47m lower than

the height of the passage would leave a gap above similar to that at

Newgrange in Ireland. An early drawing made by Gibb in 1861, however

shows the passage roof dropping down to the same height as the recess'

(More

about light-boxes)

|

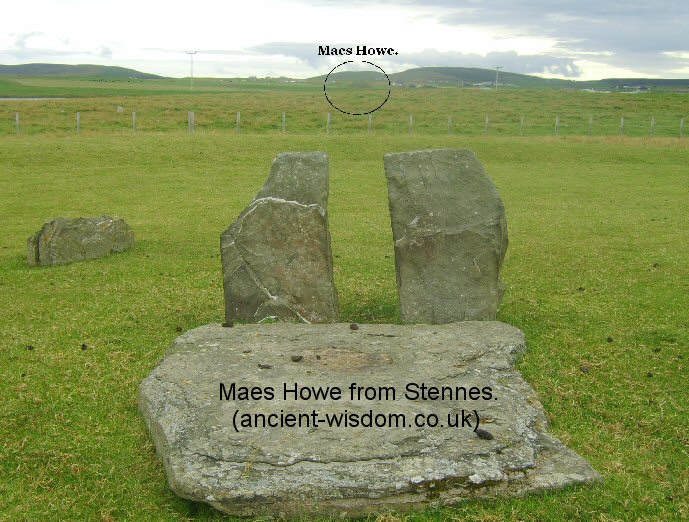

The Orkneys Complex.

Maes howe has not been dated directly,

but by association with the stone circle at

Stennes

nearby, and with the well known settlement site of

Skara Brae

on the west coast it is thought to have been erected about 3,000 BC.

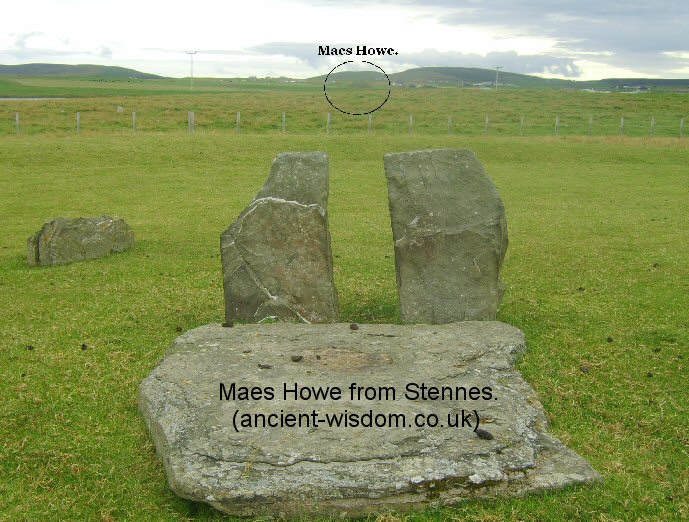

Meas Howe should not be viewed as an independent

structure. It was an integral part of the prehistoric landscape, as

the photo above illustrates. The whole area can be seen as an outdoor

ceremonial arena, with the ever-present Hills of Hoy in the background

receiving the midwinter sun and marking the new year. Archaeologists

are currently investigating the causeway that links

Stennes to

Brodgar, where several large stones

suggest a ceremonial route between the two sites.

(More about the Orkneys Complex)

|

(Other Passage

Mounds)

(Other Scottish Sites)

|

The cruciform

chamber in the centre of the mound is vaulted by a corbelled roof,

and has three small sub-chambers leading from it.

The cruciform

chamber in the centre of the mound is vaulted by a corbelled roof,

and has three small sub-chambers leading from it.