|

Prehistoric Construction Techniques.

Prehistoric Construction Techniques.

|

The earliest examples of stone masonry in both the 'Old'

and 'New' worlds demonstrates a high skill level, something which is often

suggested as being a result of the existing knowledge of carpentry at the

transition in working from wood to stone. This idea is borne out

somewhat in Egypt where for example, the masonry of the ceilings in the temples of

1st dynasty Saqqara were carved to imitate the 'reed-bundle' ceilings

of pre-dynastic Egypt. There is however, no evidence of such a

transition in the Americas.

Featured Masonry Techniques:

|

|

|

|

|

The transport and use of

unnecessarily large blocks of stone, the specific selectivity

of stone type along with various examples of 'extreme' masonry

at numerous sacred and ancient monuments is

starting to reveal a reverence for stone itself, an idea which

has foundation in mythology, religion and can still be seen

today at Jerusalem, Mecca, the 'Lignum' of India and at the

crowning of any new king or Queen in UK (i.e. Scottish

'Stone-of-scone', English 'kings-stone') etc.

It is

noticeable that there are several specific construction

techniques in the masonry of (apparently unrelated) cultures

from around the ancient world. The specific similarity in

design, technique and engineering skills is, in certain

cases very suggestive of a common source of knowledge, or at

the least - of contact between cultures. In response, it has

been argued that such similarities are

'co-evolutionary', being the natural result of working with

stone.

The following examples

demonstrate the sophisticated skills of the prehistoric masons.

|

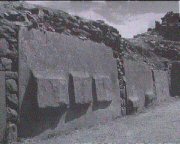

Several structures show the blocks cut

with an internal angle, so as to 'fold' the stone around corner's. It is

suggested that this was incorporated as an earthquake 'preventative'.

Valley-Temple,

Ghiza, Egypt.

- There are several stones with this design

feature in the valley-temple. It is interesting to note that the stones have been

cut so as to continue

only a short distance around the corner which hints at the idea that

style might have been involved (rather

than, or as well as, function).

Luxor, Egypt. (Left),

Machu

Pichu , Peru (Right).

|

|

It is often suggested that this

design feature was incorporated into constructions as an 'earthquake'

preventative. The fact that the constructions exist in such good condition

after so long, in itself supports this idea.

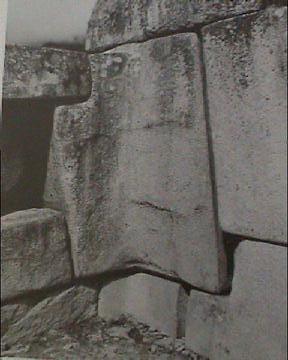

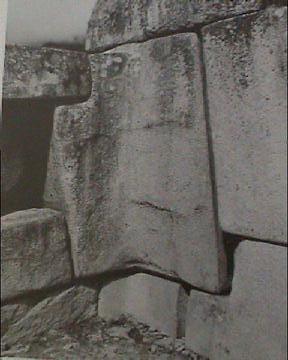

Multi-faceted stones -

Valley-temple, Ghiza, Egypt.

While the Egyptian

examples (above), followed a horizontal plane, the South American examples

(below), are polygonal, apparently following neither vertical nor horizontal

planes, a process which would have required a considerably higher level of

technical skill.

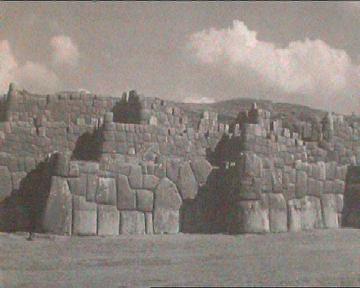

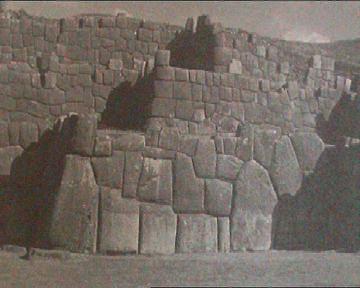

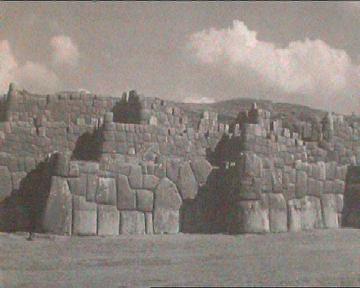

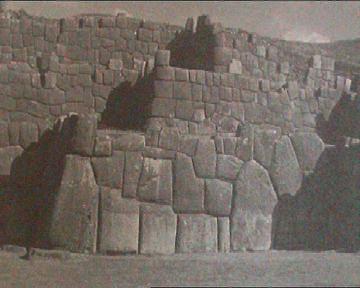

The Inca masonry of south America is probably the

finest the world has ever seen.

S. America,

Cuzco.

'Stone of the twelve Angels'.

(2)

Sacsayhuaman -

One of the greatest walls of all time.

One of the 300 Ahu Platforms surrounding

Easter Island. Made of Basalt and with blocks

several tons each, The style of masonry shows a stark similarity to South

American masonry examples above.

|

|

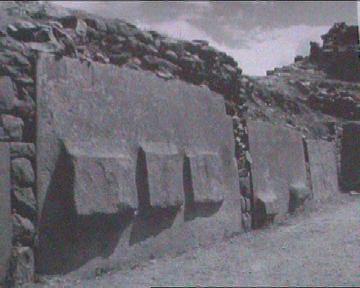

Another construction feature commonly

suggested as an earthquake preventative is the means used to join huge

blocks together. It is believed that copper (or silver) was used at

Tiahuanaco (below), both of which are soft metals.

Some examples from the 'Old-World' (Namely Egypt, and Cambodia)..

From left to right:

Angkor Watt,

Karnak,

and

Denderra.

And from the 'New-World'.:

Tiahuanaco,

and

Ollantaytambo.

It has also been suggested that these 'ties'

were employed to 'ground' structures properly (often made of conducting

Quartzite).

|

|

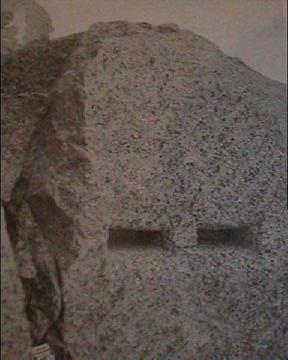

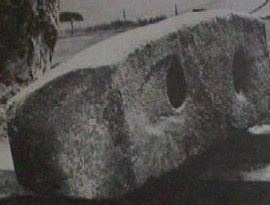

Quarry-Marks (for splitting stone): |

|

The megalithic builders employed the same method of splitting quartz, at different

locations all around the world. This is not unusual, as it is probably the best

method, and is still widely used today. By far the easiest way of splitting

Quartz stone is to chip a series of holes into the stone, which are then

packed with 'wedges and shims' (made of wood). Following the addition

of water, the wedges expanded and the stone splits along the line.

Examples from S. America:

Left: Machu Pichu

(1)

and Right: Cuzco.

From

Egypt: Menkaure's pyramid,

Giza (left), and

at Aswan (right).

From

Carnac, France, (left), and

Castleruddery, Ireland (right).

More examples from Portugal (left), and From

Malta

(right).

(Click here for more on this

subject)

|

| 'Manoeuvring

Protuberances' : |

|

These small protuberances are found on the oldest (and arguably most sacred)

Egypt and South American constructions. They are generally assumed to have functioned as

'hitching points' for

manoeuvring the blocks into place, however there are several examples where they

have been left as if to demonstrate some other meaning...

The 'Boss' mark on the stone above the passage entry into the 'King's

chamber' in the great pyramid is often suggested as being the remains of one

of these protuberances.

They are found on the exterior granite facing-stones of Menkaure's Pyramid at Giza.

It is possible to see how the process of smoothing off of

the granite casing stones was started on the Eastern face of Menkaures pyramid. The smoothing process was achieved with

the use of Dolerite mauls which were able to pound the softer granite. This

process can still be seen today at the Aswan granite quarries, where the

granite for Giza originally came from.

The same marks are also found in the

Osireion, at Abydoss. One of the several reasons to support

the theory that it was

contemporary with the Valley temple at Ghiza.

Similar 'protuberances' can be seen at several Inca sites in

South America.

At Ollantaytambo,

Peru, the 'protuberances' take on a whole different meaning altogether, as

they could almost be classed as stylised over functional.

Although both locations

have the same 'protuberances', the Inca block-work was multi-faceted, while

at Ghiza, they were laid in even courses.

|

|

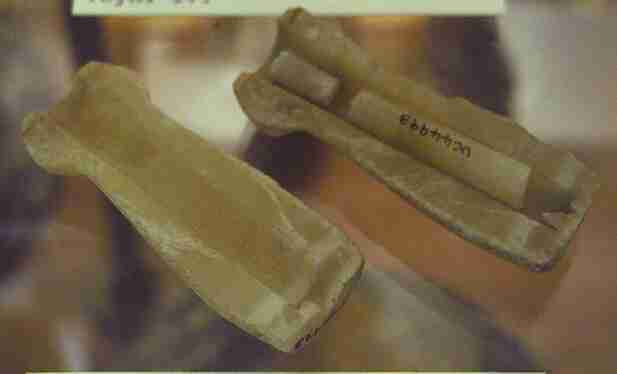

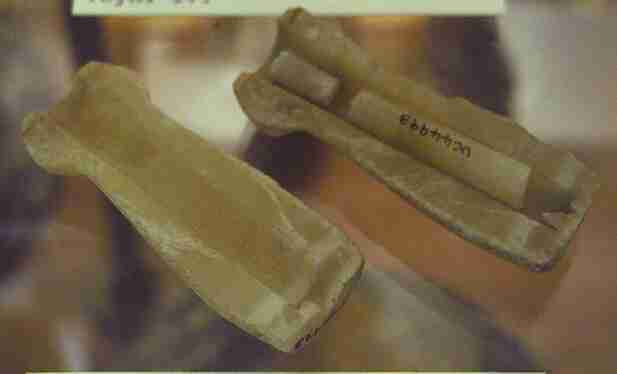

Mortise and Tenon Joints: |

It is perhaps surprising to find that some of

the earliest known examples of masonry exhibit a sophisticated

understanding of joinery. This particular construction feature is reasonably

explained as having followed the transition from building structures

first from wood then stone.

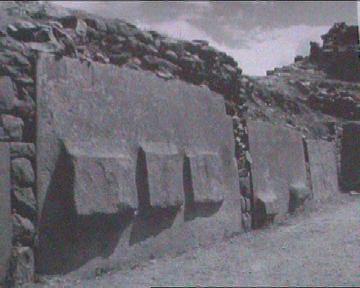

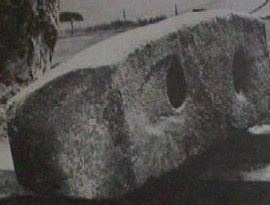

Some examples of the Various 'Mortise and

Tenon' joins used in the construction of

The Osirion, at Abydoss,

in Egypt. This is considered one of the oldest buildings in Egypt, and

is quoted as having only one other structure of contemporary design, that being

the Valley-Temple at Giza. Both

structures used the technique of continuous-lintelled trilithon's, seen also

at Stonehenge III.

(Click here for a comparison of

the two structures)

Mortise-and-tenon joints had, of course, been used previously in Bronze Age

ships in Egypt, as in the construction of the Khufu�s boat at Giza (ca. 2600

B. C.) and Senwosret III�s boats (ca. 1850 B.C.) at Dashur (Lipke 1984, 64;

Steffy 1994, 25-27, 32-36, Patch and Haldane 1990). These early Egyptian

examples of mortise-and-tenons, however, were freestanding and not pegged to

lock adjacent strakes to one another. Rather, their primary function was to

align the planks during construction, which were then fastened to each other

with ligatures. This tradition of shipbuilding appears to have persisted at

least as late as the 5th century B.C. when Herodotus observed

nearly identical construction methods still in use in Egypt. In his

oft-cited quotation, Herodotus noted that short planks were joined to each

other with long, close-set tenons, which were then bound in the seams from

within with papyrus fibers (Haldane & Shelmerdine 1990). There is no

mention of locking the close-set tenons with pegs. The Egyptians were,

however, fully aware of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints at last since the

Old Kingdom (Dynasty III: ca. 2700-2600 B. C.) and used them in woodwork

requiring this type of fastening (Lucas & Harris 1962, 451), but, as far as

we can determine, they did not resort to their use in shipbuilding, unless

they restricted their use to seagoing ships only, for which we have

surviving examples.

(9)

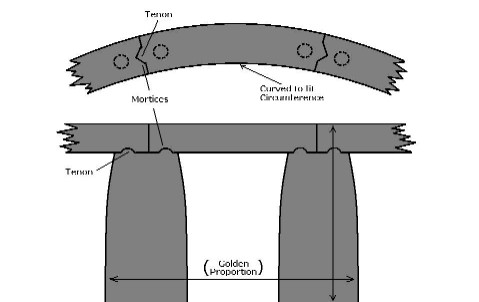

The

Stonehenge Sarsen Stones :

In its complete form the outermost stone setting would have consisted of a circle of 30

upright sarsen stones, of which 17 still stand, each weighing about 25 tons.

The tops of these uprights were linked by a continuous ring of horizontal

sarsen lintels, only a small part of which is now still in position. The

stones in the sarsen circle were carefully shaped and the horizontal lintels

joined not only by means of simple mortise-and-tenon joints, but they were

also locked using what is effectively a dovetail joint. The edges were

smoothed into a gentle curve which follows the line of the entire circle.

The sarsen-ring at

Stonehenge (whose

official inner diameter is 97ft or 1162.8 primitive inches), has a

circumference of 3652.4 primitive inches. Note: This is also exactly one

�quarter-aroura�, as measured in ancient Egypt

(1). Sir Norman Lockyer

also detected similarities between the masonry of the Blood/Chalice-well

at

Glastonbury and

that which

he

had seen in Egypt.

The pictures above illustrate the sophisticated

construction techniques applied to the

Stonehenge sarsen-stones, which are

dated at approximately 2,500 BC, however if we follow Lockyer's lead, and

look closer at Egyptian masonry, we find similar features were applied to

construction of the the Osirion (above), a temple dated to a far earlier

time, and a site suggested by Lockyer to have alignments suggesting an

association to the summer-solstice sunrise

(2).

(More about Stonehenge)

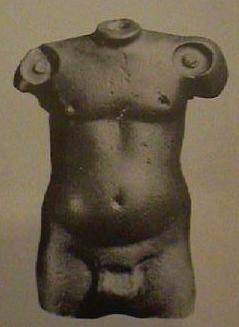

And finally, from the Indus Valley Culture...

This incredible stone casting is from Harappa in

Pakistan (c. 2,500-2,100 BC).

|

It was claimed by Petrie

that early dynastic Egyptians used drills for some of their

constructions. The following images suggest he was right.

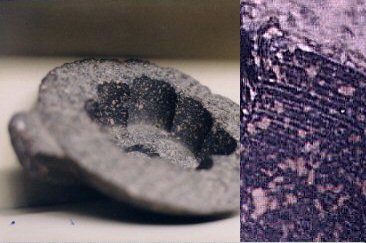

Evidence for

drilling in ancient Egypt. Marks in the kings-coffer suggest that it

too was hollowed by core-drilling.

The Capstones of Pierres Plates in France

have what appear to be drill-marks on the top-sides.

The 'Drill-marks' on some stones match those on

others, suggesting they were split in half.

(More

about Pierres plates) Surgical Drilling in

Prehistory.

Although not directly

connected with construction, evidence for drilling goes back

several thousand years, as testified by the numerous examples

of prehistoric dentistry and Trepanning, both involving

drilling procedures. Article: MSNBC (2006) - Proving

prehistoric man�s ingenuity and ability to withstand and inflict

excruciating pain, researchers have found that dental drilling dates

back 9,000 years. Primitive dentists

drilled nearly perfect holes into live but undoubtedly unhappy patients

between 5500 B.C. and 7000 B.C., an article in Thursday�s issue of the

journal Nature reports.

Researchers carbon-dated at least nine skulls with 11 drill holes found

in a Pakistan graveyard.

(Link to full article:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12168308/)

Trepanation:

Skulls with signs of trepanning were found practically in all

parts of the world where man has lived. Trepanning is probably

the oldest surgical operation known to man: evidence for it

goes back as far as in 40,000 year-old Cro-Magnon sites. The

Egyptians invented the circular trephine, made by a tube with

serrated borders, which cuts much easier by means of rotation,

and which was then extensively used in Greece and Rome, and

gave origin to the "crown" trephine, used in Europe from the

first to the 19th century. Trepanation:

Skulls with signs of trepanning were found practically in all

parts of the world where man has lived. Trepanning is probably

the oldest surgical operation known to man: evidence for it

goes back as far as in 40,000 year-old Cro-Magnon sites. The

Egyptians invented the circular trephine, made by a tube with

serrated borders, which cuts much easier by means of rotation,

and which was then extensively used in Greece and Rome, and

gave origin to the "crown" trephine, used in Europe from the

first to the 19th century.

(Link to full

article:

http://www.cerebromente.org.br/n02/historia/trepan.htm )

(More about Prehistoric Surgery)

Hundreds of uniformly drilled holes on the stones at

Mnajdra, Malta.

(More about Drilling in Prehistory) |

|

The Use of Concrete in Ancient Structures: |

|

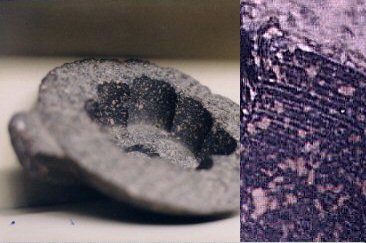

'The

Hair in the Rock',

Egypt: Prof. Dr. Joseph Davidovits of the French Geopolymer

Institute discovered a hair sticking out of a boulder of the Cheops (Khufu)

pyramid of Giza). He concluded that either the hair was older than the rock

surrounding it, (meaning the rock formed later), or the boulder is

synthetic. Either of which is pretty amazing.

Examination and measurements of the boulders used in building

the pyramid show an unusually high moisture content (apparently the kind one

would expect to find in concrete).

The photo

(right), is from the pavement surrounding the pyramids at Giza. It has been

shown that this pavement was

accurately levelled to less than 0.5 inch

across the whole site, which makes it a spectacular masonry achievement in

its own right. However, of more immediate interest is the thin sliver of

limestone that has remained next to the black basalt rock behind it.

The original advocate for this theory

was

Prof. Dr. Joseph Davidovits, whose original statements in the

1980's were at first ridiculed, but which have now, following rigorous

analysis, appear to have been reasonably substantiated.

The following scientific treaty was written in 2006 and

supports Davidovit's original theory. (Although Egyptologists still adamantly refuse to

accept such an idea it is gradually gaining support).

|

Article: Science Daily. 2006:

Professor Finds Some Pyramid Building Blocks Were Concrete.

In partially solving

a mystery that has baffled archaeologists for centuries, a Drexel

University professor has determined that the Great Pyramids of Giza were

constructed with a combination of not only carved stones but the first

blocks of limestone-based concrete cast by any civilization.

The longstanding belief is that the

pyramids were constructed with limestone blocks that were cut to shape

in nearby quarries using copper tools, transported to the pyramid sites,

hauled up ramps and hoisted in place with the help of wedges and levers.

Barsoum argues that although indeed the majority of the stones were

carved and hoisted into place, crucial parts were not. The ancient

builders cast the blocks of the outer and inner casings and, most

likely, the upper parts of the pyramids using a limestone concrete,

called a geopolymer.

The type of concrete

pyramid builders used could reduce pollution and outlast Portland

cement, the most common type of modern cement. Portland cement injects a

large amount of the world's carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and has a

lifespan of about 150 years. If widely used, a geopolymer such as the

one used in the construction of the pyramids can reduce that amount of

pollution by 90 percent and last much longer. The raw materials used to

produce the concrete used in the pyramids -- lime, limestone and

diatomaceous earth -- can be found worldwide and is affordable enough to

be an important construction material for developing countries.

(Click

here for full article) |

As well as the suggestion that the

blocks themselves may have been made of cement, Petrie

himself identified

that it was also used

between the

blocks. The whole of the Great pyramid was originally covered with a

coat of polished limestone blocks. The faces of these blocks have

butting surfaces cut to within 1/100 of an inch of mathematical

perfection. Petrie said this of it:

...'the mean

variation of the cutting of the stone from a straight line and from

a true square is but 0.1 inch in a length of 75inches up the face,

an amount of accuracy equal to the most modern opticians' straight

edges of such a length. These joints, with an area of some 35 square

feet each, were not only worked as finely as this, but

were cemented throughout.

Though the stones were brought as close as 1/500 of an inch, or, in

fact, into contact, and the mean opening of the join was 1/50 of an

inch, yet the builders managed to fill the joint with cement,

despite the great area of it, and the weight of the stone to be

moved- some 16 tons. To merely place such stones in exact contact at

the sides would be careful work, but to do so with cement in the

joints seems almost impossible'.

(8)

The highly polished

limestone casing stones that covered the pyramid were

fixed

with a 'fine aluminosilicate cement'.

The finished pyramid contained approximately 115,000 of these stones,

each weighing ten tons or more. These stones were dressed on all six of their sides,

not just the side exposed to the visible surface, to tolerances of .01

inch. They were set together so closely that a thin razor blade could not

be inserted between the stones.

Egyptologist Petrie

expressed his astonishment of this feat by writing: - 'Merely to place

such stones in exact contact would be careful work, but to do so with

cement in the joint seems almost impossible; it is to be compared to the

finest opticians' work on the scale of acres".

Extract from Petrie -

The use of plaster by the Egyptians is remarkable; and their skill in

cementing joints is hard to understand. How, in the casing of the Great

Pyramid, they could fill with cement a vertical joint about 5 X 7 feet in

area, and only averaging 1/50 inch thick is a mystery; more especially as

the joint could not be thinned by rubbing, owing to its being a vertical

joint, and the block weighing about 16 tons. Yet this was the usual work

over 13 acres of surface, with tens of thousands of casing stones, none

less than a ton in weight.

Extract from Petrie -

From several indications it seems that the masons planned the casing and

some at least of the core masonry also, course by course on the ground.

For on all the casing, and on the core on which the casing fitted, there

are lines drawn on the horizontal surfaces, showing where each stone was

to be placed on those below it. If the stones were merely trimmed to fit

each other as the building went on, there would be no need to have so

carefully marked the place of each block in this particular way; and it

shows that they were probably planned and fitted together on the ground

below. Another indication of very careful and elaborate planning on the

ground is in the topmost space over the King's Chamber; there the

roofing-beams were numbered, and marked for the north or south sides; and

though it might be thought that it could be of no consequence in what

order they were placed, yet all their details were evidently schemed

before they were delivered to the builders' hands. This care in arranging

all the work agrees strikingly with the great employment of unskilled

labourers during two or three months at a time, as they would then raise

all the stones which the masons had worked and stored ready for use since

the preceding season.

(Other examples

of extreme Egyptian masonry)

Maltese concrete (Torba)

Ggantija Ggantija , Malta

-

The

temples on Malta are claimed to be some of the oldest free-standing temples in the

world.

A. Service

(6),

mentions the 'contemporary cement of the floor'

in the pavement of the Ggantija temple on Gozo, Malta (see

left), and

although the idea was not accepted for a long

time,

The pictures below show how some of the

temple floors

were paved with huge stones, a process also visible at several Maltese temples (Tarxien,

left and

Ggantija,

right).

(More about the

Constructions of Prehistoric Malta)

|

| The

Specific Selection of Stone: |

While it is apparent that the

megalithic builders showed a preference for certain stone types, the

reason for this has yet to be explained satisfactorily. The extra

distance and effort required to employ specific stones in ancient

structures offers us with a clue as to the possible motivation of

the builders.

The immense White-quartz, portal-stones at

Castelruddery Henge-Circle in Ireland.

(More

about the Specific Selection of Stone in Prehistory)

|

Trepanation:

Skulls with signs of trepanning were found practically in all

parts of the world where man has lived. Trepanning is probably

the oldest surgical operation known to man: evidence for it

goes back as far as in 40,000 year-old Cro-Magnon sites. The

Egyptians invented the circular trephine, made by a tube with

serrated borders, which cuts much easier by means of rotation,

and which was then extensively used in Greece and Rome, and

gave origin to the "crown" trephine, used in Europe from the

first to the 19th century.

Trepanation:

Skulls with signs of trepanning were found practically in all

parts of the world where man has lived. Trepanning is probably

the oldest surgical operation known to man: evidence for it

goes back as far as in 40,000 year-old Cro-Magnon sites. The

Egyptians invented the circular trephine, made by a tube with

serrated borders, which cuts much easier by means of rotation,

and which was then extensively used in Greece and Rome, and

gave origin to the "crown" trephine, used in Europe from the

first to the 19th century.