|

Extreme Egyptian Masonry:

(Egyptian Masonry Skills).

Extreme Egyptian Masonry:

(Egyptian Masonry Skills).

It is not

surprising that the occasional eyebrow was raised in the past

concerning the extent of the Egyptian masonry skills during the

Early dynastic period. Not only were the structures superior in

a visionary capacity, but also in precision, design and

execution. The Dynastic period of Egypt heralded a time of

extraordinary achievement, it was the age of the pyramid

builders when some of the largest and most sophisticated

structures of all time were built, including the last remaining

'Seven-Wonders' of the ancient world, all built in the

Neolithic period.

Although

apparently spontaneous, the technology underlying these huge

constructions and was built on a foundation of science and

mathematics which in turn, has provided us with traces of their

manufacturing processes which are proving equally astonishing.

Quick Links:

|

Machine Tools in Ancient

Egypt: |

Although the idea was first raised by Petrie, it has resurfaced recently

through the work of Clive Dunn

(1), who provides good evidence of 'Machined'

artefacts at Giza. He reminds us that Petrie also recognised that the few

remaining tools from the period were 'insufficient to explain Egyptian

artefacts'. Although the idea was first raised by Petrie, it has resurfaced recently

through the work of Clive Dunn

(1), who provides good evidence of 'Machined'

artefacts at Giza. He reminds us that Petrie also recognised that the few

remaining tools from the period were 'insufficient to explain Egyptian

artefacts'.

Dunn reviewed certain igneous

artefacts inspected by Petrie and concluded that they 'almost undeniably

indicate machine power was used by the pyramid builders'.

(1)

Egyptologists maintain that

the work (including granite), was completed with copper and stone tools, although this has been contested on the basis that

the spiral tool-marks in

certain core samples indicate that a metal (or precious stone) stronger than copper would have

been required.

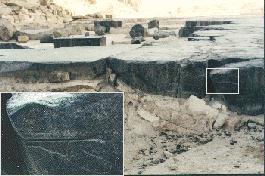

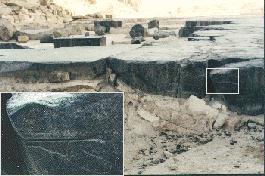

The photo (right), is a

close-up of the tool-marks on a granite sample. Their definition, length and

regular separation denote the use of both a harder-than-granite tip, and a

constant pressure.

Core-drilling - There is

plenty of evidence that core-drills

were used at Giza. The classic example being the tool-marks found inside

the sarcophagus of the Great pyramid. As the stone that was being cut is

granite, the surface of the drill-tip would have had to have included a

material of equal or greater hardness in order to cut through the stone.

In itself, this is an amazing achievement, but

when we look closer at the remaining drill marks, it is evident that a great

amount of downwards pressure was applied to the drills as well, more than

can be explained by conventional theory. The distance between the grooves

created by core-drilling can be use as a measure of how much force was

applied as drilling was in process. Dunn said of this In itself, this is an amazing achievement, but

when we look closer at the remaining drill marks, it is evident that a great

amount of downwards pressure was applied to the drills as well, more than

can be explained by conventional theory. The distance between the grooves

created by core-drilling can be use as a measure of how much force was

applied as drilling was in process. Dunn said of this

'On the granite core, No 7, the spiral of the

cut sinks 0.1 inch in the circumference of 6 inches, or 1 in 60, a rate of

ploughing out the quartz and feldspar which is astonishing'. The

feed-rate of modern drills, Dunn calculates to be 0.0002 inch per

revolution, indicating that the Egyptians drilled into granite with a

feed-rate that was five hundred ties greater or deeper per revolution of the

drill than modern drills.

(1)

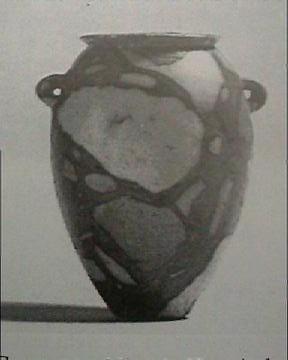

Mass-Produced lathe-cut vases -

Petrie submitted evidence that showed that the ancient Egyptians used

Lathes. Mass-Produced lathe-cut vases -

Petrie submitted evidence that showed that the ancient Egyptians used

Lathes.

It appears that vase

making was a considerable post in ancient Egypt. We can read an inscription

concerning 'Imhotep' which tributes him as the 'Chief vase maker' amongst

his many titles. There have been literally thousands of stone-carved vases

found in and around Saqqara, which are all

considered to have originated from the first dynastic periods. Many of the

vases have been cut from extremely hard stone, again requiring an equal or

harder blade to cut them with.

The evidence suggests that a specialised drill

would have been used to carve the interiors, which are remarkable in that

they have been carved equally well as the outsides, including the difficult

section inside and under the curve of the 'necks' of the vases.

Dunn

(1), says 'There is also evidence of

clearly defined lathe tool marks on sarcophagi lids'. The sheer scale

of these lids makes this a bold suggestion, which he confidently supports

with the observation that a Sarcophagus lid in the Cairo museum shows

evidence of 'tool marks that indicate these conditions exactly where one

would expect to find them'.

(1)

Experimental Archaeology: Stone Vase

Production.

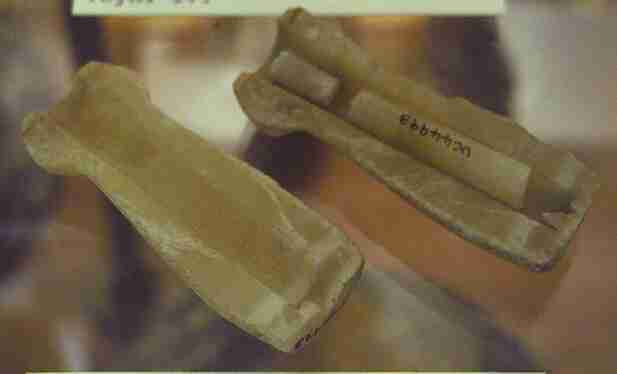

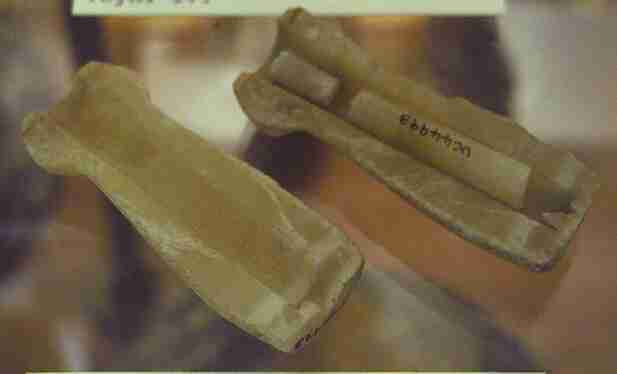

The suggestion of 'machined' drilling has been

explored by Dennis Stocks, an experimental archaeologist. His

research sheds considerable light on the means whereby stone vases

could be made using equipment available to Egyptians at the time.

The resulting tool-marks have been shown to match those found in

early dynasty stone vases, being produce not by a continuous

revolving drill, but rather with a twist/reverse twist motion

creating two arcs, as produced by using the following hand tool,

rotating left, then right, then left etc. This system provides a

suitable explanation for the production of stone vases made of

alabaster or limestone, but we are still left without a suitable

explanation for the core-drilling seen in granite and obsidian vases

and sarcophagus.

(Left) stone borer, (Right) Images from 12th

and 18th dynasty tombs showing the manual production of vases.

(Link

to Article by Dennis Stocks)

Other Examples:

This schist disc was

discovered at Saqqara. Its purpose is only to be guessed at. It is

approximately 30cm in diameter, and is only 1cm thick.

It is currently on

display in the Cairo museum, and is labelled as an incense container,

although there is no evidence to support this. What is certain is that at

this early time (Early Dynasty period), stone carving is already a sophisticated skill.

This finely carved stone

'funnel' is also from early dynastic Egypt. It is also currently on

display in the Cairo museum.

This Schist (slate) plate is from the 3rd

dynasty. It shows the same folded corners as the disc above from

Saqqara. It is also currently on display in the Cairo museum.

|

|

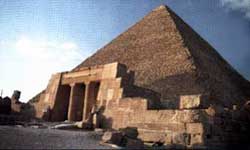

Extreme Masonry at the Giza Plateau: |

It is often

forgotten that before the pyramid was built, that the limestone

plateau beneath was first levelled, and over it was placed a

platform of carefully cut stones which can still be seen to protrude

from under the pyramids base. This platform is around 0.5m thick and

despite the passing of time and several earthquakes, remains level

to within 0.8 of an inch (21mm) over the entire Giza plateau.

The whole of the

Great pyramid was originally covered with a coat of polished

limestone blocks which would have originally given the

aspect of Giza a

smooth and perfect finish all over. The faces of these blocks have

butting surfaces cut to within 1/100 of an inch of mathematical

perfection.

Petrie said

this of it:

...' the

mean variation of the cutting of the stone from a straight line

and from a true square is but 0.1 inch in a length of 75 inches

up the face, an amount of accuracy equal to the most modern

opticians' straight edges of such a length. These joints, with

an area of some 35 square feet each, were not only worked as

finely as this, but were cemented throughout. Though the stones

were brought as close as 1/500 of an inch, or, in fact, into

contact, and the mean opening of the join was 1/50 of an inch,

yet the builders managed to fill the joint with cement, despite

the great area of it, and the weight of the stone to be moved-

some 16 tons. To merely place such stones in exact contact at

the sides would be careful work, but to do so with cement in the

joints seems almost impossible'.

(7)

Saw-Marks in

the basalt stones on the east side of the Great pyramid at Giza:

The

basalt pavement stones are irregular in thickness, and sometimes

rounded on the bottom side. They were placed on top of blocks of

Tura limestone which had previously been fitted to the

underlying bedrock. It appears from the following photo's that

the basalt blocks were cut to level 'in situ' (after they had

been put in place on the ground).

The

crisp and parallel the edges demonstrate the high quality of

this work and indicates that the blade was held completely

steady. It appears that cutting basalt was not so slow and

arduous that extra cuts like these would have been avoided as

being an unnecessary waste of time. There are several places

where over-cuts like these can be seen. If you find this spot,

look around behind you to the north - there are several more

within 30 ft. In one place you can find many vertical parallel

saw cuts right next to each other.

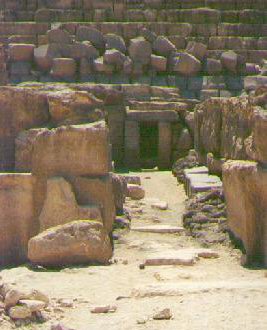

There are several extraordinary sized stones recorded at the Giza plateau,

with the largest regularly estimated at over 400 tons....

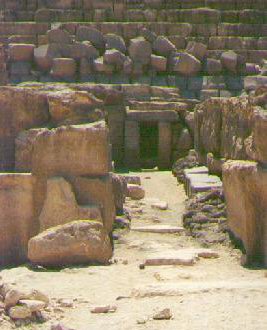

Temple East of 'Khafres' Pyramid.

'Largest stone

estimated 468 ton block'

(11).

(J. Cook; The Pyramids of Giza; p. 22). - 'Khafre

foundation stones > 400 tons'.

Mortuary temple

of Menkaure

(Mycerinus).

[Edwards, p. 265] - 200 tons

http://atschool.eduweb.co.uk/ - 285 tons

'Reisner

estimated that some of the blocks of local stone in the walls of the

mortuary temple weighed as much as 220 tons, while the heaviest granite

ashlars imported from Aswan weighed more than 30 tons'.

Ref:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyramid_of_Menkaure)

The

'Valley

Temple'

-

The Valley temple was built from huge granite blocks in the style of the Osireion at Abydoss.

They are estimated at around 50 tons + each. The whole temple in turn was encased in

even larger limestone blocks, the largest of which has been (enthusiastically) estimated at

around 200 tons.

The 'Great' pyramid of Khufu - The 'Kings chamber' in the Great

pyramid is covered over with several granite stones estimated at 50-70 tons

each. The Gable stones over the entrance (left) and several of the stones covering

the descending passage are also several cubic metres in size.

Maximum weight of stone in great pyramid:

( Guinness,

p. 119). 50 tons

(R. J. Cook; The

Pyramids of Giza; p. 22).70 tons

(The

largest stones of all time)

|

(More

about the Giza Plateau)

|

Obelisks (Ben-bens and pyramids): |

What is not commonly known is that

all the large 3rd - 5th dynasty pyramids around Giza (The Heliopean

Pyramids) were built so that their corners aligned exactly towards

Heliopois. This architectural fact leads to the idea that the

pyramids were nothing more than large ben-ben's themselves, pointing to the Northern home of the Obelisk, Heliopolis. (In the

South of Egypt, the Obelisk 'Capital' was Karnak).

Hatshepsut's obelisk barge.

This image

reveals an important engineering factor for moving large stones:

Namely, that they are lighter in water... The transport of heavy

stones by water is suspected at several ancient sites such as

Stonehenge, Giza and Carnac.

Herodotus described moving the

580 ton "Green Naos" under Nectanebo II: "This took three years

in the bringing, and two thousand men were assigned to the

conveying of it ..." (History, 2.175)

Pliny wrote of the

transportation of an "eighty cubit" obelisk under Ptolemy II:

According to some

authorities, it was carried downstream by the engineer

Satyrus on a raft; but according to Callixenus, it was

conveyed by Phoenix, who by digging a canal brought the

waters of the Nile right up to the place where the obelisk

lay. Two very broad ships were loaded with cubes of the same

granite as that of the obelisk, each cube measuring one

foot, until calculations showed that the total weight of the

blocks was double that of the obelisk, since their total

cubic capacity was twice as great. In this way, the ships

were able to come beneath the obelisk, which was suspended

by its ends from both banks of the canal. The blocks were

unloaded and the ships, riding high, took the weight of the

obelisk. (Natural History, 36.14).

(Obelisks and Menhirs Homepage)

|

Concrete in the Pyramids: |

It has been suggested that concrete

might have been used in certain ancient structures. As incredible as it

may seem, there is evidence to support this idea.

In addition to

achieving seamless joins between blocks, the

highly polished limestone casing stones that covered the pyramid

were

fixed with a

'fine aluminosilicate cement'.

The finished pyramid contained approximately 115,000 of these

stones, (Over 13 acres), each weighing ten tons or more. These

stones were dressed on all six of their sides, not just the

side exposed to the visible surface, to tolerances of .01 inch. They

were set together so closely that a thin razor blade could not be

inserted between the stones.

Egyptologist Petrie expressed his astonishment of

this feat by writing: - 'Merely to

place such stones in exact contact would be careful work, but to

do so with cement in the joint seems almost impossible; it is to

be compared to the finest opticians' work on the scale of acres"

'The Hair in the Rock' - Prof. Dr. Joseph Davidovits of the French Geopolymer

Institute discovered a hair sticking out of a boulder of the Cheops

(Khufu) pyramid of Giza.

He concluded that either the hair is older than the rock surrounding

it, meaning the rock formed later, or the boulder is synthetic.

(Either of which is pretty amazing)...

Examination and measurements of the boulders

used in building the pyramid show an unusually high moisture content (similar

to that found in concrete).

The seam joins between

the basalt and the limestone pavements:

Basalt was used for the paving stones, still visible, in

the Pyramid Temple of Khufu. It is suggested to have come from a quarry in the Faiyum,

west of Dahshur.

(The fine sliver of remaining limestone is

suggestive of either cement or 'moulded' masonry)

Concrete (Torba) is also known to

have been used in the floor of the

Ggantija

temple on Gozo (Malta).

(More about the use of concrete in prehistoric buildings)

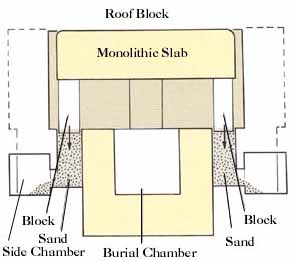

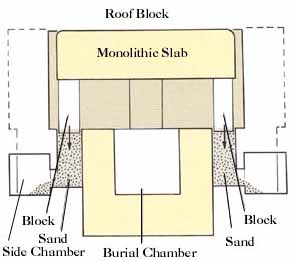

One thing that is greatly over-looked is the

incredible sized stones used in the burial vaults of the Pharaohs. It is unclear whether they had much clearance to install these vaults or how they lowered them.

Several 5th and 6th

Dynasty pyramids included gabled roofs with blocks weighing up to 90

tons but the

subject is mostly ignored so it is hard to check facts. Some of them

are known to have a clearance of less than an inch. This may have

involved sliding it in straight in order to get it in place which

would be extremely difficult with a vault that may have weighed over

100 ton.

The Sarcophagus of Amenemhet III , Egypt.

The

quartzite sarcophagus of Amenemhet III weighing 110 metric tons (121

Imperial tons), was placed in a chamber with an interior

length of 7 metres and walls 1 metre thick.

(16)

The monolithic lid was lowered onto the sarcophagus by means of

sand-flow, and the chamber was later covered with another two huge

50-ton limestone vaulting stones.

Above the burial

chamber were 2 relieving chambers. This was topped with 50 ton

limestone slabs forming a pointed roof. Then an enormous arch of

brick 3 feet thick was built over the pointed roof to support the

core of the pyramid.

(26)

The

sarcophagus was found to be empty when opened.

(The

Great Puzzle of Giza: An In-depth analysis of the Great Pyramid)

(Extreme

Masonry from around the Ancient World)

(Prehistoric

Construction Techniques)

(Pyramids

Homepage)

(Prehistoric

Egypt Homepage)

|

Although the idea was first raised by Petrie, it has resurfaced recently

through the work of Clive Dunn

(1), who provides good evidence of 'Machined'

artefacts at Giza. He reminds us that Petrie also recognised that the few

remaining tools from the period were 'insufficient to explain Egyptian

artefacts'.

Although the idea was first raised by Petrie, it has resurfaced recently

through the work of Clive Dunn

(1), who provides good evidence of 'Machined'

artefacts at Giza. He reminds us that Petrie also recognised that the few

remaining tools from the period were 'insufficient to explain Egyptian

artefacts'.

In itself, this is an amazing achievement, but

when we look closer at the remaining drill marks, it is evident that a great

amount of downwards pressure was applied to the drills as well, more than

can be explained by conventional theory. The distance between the grooves

created by core-drilling can be use as a measure of how much force was

applied as drilling was in process. Dunn said of this

In itself, this is an amazing achievement, but

when we look closer at the remaining drill marks, it is evident that a great

amount of downwards pressure was applied to the drills as well, more than

can be explained by conventional theory. The distance between the grooves

created by core-drilling can be use as a measure of how much force was

applied as drilling was in process. Dunn said of this Mass-Produced lathe-cut vases -

Petrie submitted evidence that showed that the ancient Egyptians used

Lathes.

Mass-Produced lathe-cut vases -

Petrie submitted evidence that showed that the ancient Egyptians used

Lathes.