|

Vitrification:

(Ancient Examples of..)

Vitrification:

(Ancient Examples of..)

Vitrification occurs as a result of exposing silica or

stone to extreme heat. The process has been determined at several

ancient sites around

the world. While some can be shown to have been caused naturally, there

have been several recent studies that show it to have been done as a

deliberate act.

Quick-links:

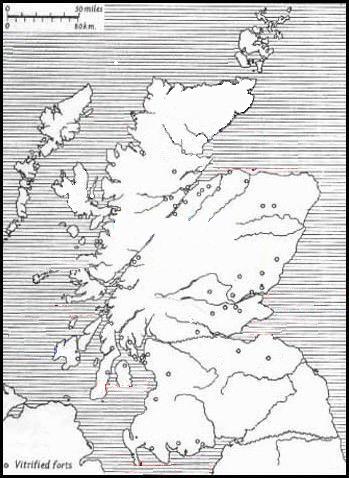

Vitrified ruins have been found Scotland, England, Ireland,

France, Turkey, Iran, Germany and elsewhere, however, out of some 100 forts

identified throughout the world, more than half are located in Scotland.

What is a vitrified Fort?

A Vitrified fort is a 'hill-fort' with stone ramparts/walls

which shows evidence of having been subjected to extreme heats (over 1000˚C),

causing the rocks to melt and fuse together. Although in some cases, this

may have occurred accidentally, but there are several factors which indicate

that it was a deliberate act.

How does Vitrification occur?

There is still some debate over the exact method whereby

such high temperatures were achieved outdoors, but in principle, it is

generally accepted that burning was the method of causing vitrification.

Experiments carried out in the 1930s by the famous

archaeologist V. Gordon Childe and his colleague Wallace Thorneycroft showed

that forts could be set on fire and generate enough heat to vitrify the

stone. In 1934, these two designed a test wall that was 12 feet long, six

feet wide and six feet high, which was built for them at Plean Colliery in

Stirlingshire. They used old fireclay bricks for the faces and pit props as

timber, and filled the cavity between the walls with small cubes of basalt

rubble. They covered the top with turf and then piled about four tons of

scrap timber and brushwood against the walls and set fire to them. Because

of a snowstorm in progress, a strong wind fanned the blazing mixture of wood

and stone so that the inner core did attain some vitrification of the rock

Deliberate Vitrification:

The analysis of vitrified forts

has provided us with enough evidence to show that vitrification, in

most cases at least, was a deliberate act. The following examples

demonstrate.

-

There are some forts which have been placed

on practically infusible rock, such as the quartzose conglomerates of the

Old Red Sandstone, as at Craig Phadraic, and on the limestones of Dun Mac

Uisneachain. In these examples, pieces of fusible rocks have been selected

and carried to the top from a considerable distance demonstrating that the

act of vitrification was deliberate.

-

The vitrified walls of the Scottish forts

are invariably formed of small stones which could be easily acted upon by

fire, whereas the outer ramparts where used, are not vitrified and are built

of large blocks. Many of the continental forts are so constructed that the

fire must have been applied internally, and at the time when the structure

was being erected. Daubr�e, in an analysis which he made on vitrified

materials taken from four French forts, and which he submitted to the

Academy of Paris� in February 1881, found the presence of natron in such

great abundance that he inferred that sea-salt was used to facilitate fusion

again suggesting that it was a deliberate act.

-

Hamilton describes several sites in detail, including

Arka-Unskel, which he found that the rampart of local Gneiss was covered

with imported feldspatic sanstone in order to create the vitrified effect.

This method found also in the vitrified fort of Dun Mac Snuichan, on Loch

Etive.

Examples of Scottish Vitrified Forts.

Location

- Scotland. Ross & Cromarty (Highland region), 2.5 miles west of Dingwall

Description

- The hilltop crowned by this fort is scattered with lumps of vitrified

rock.

Location

- Scotland. Kirkcudbright/Dumfries & Galloway Region, 4 miles south of Dalbeattie

Description

- The fort was first built in the late 'Bronze age' or early 'Iron age', and

finds show that it was in use until the 2nd century AD, iron smelting and metalworking being carried on

there. The site has traces of a massive stone wall, now vitrified.

The following item appeared in

the New York Herald Tribune on February 16, 1947 (and was

repeated by Ivan T. Sanderson in the January 1970 issue of his

magazine, Pursuit):

'When the first atomic bomb exploded in

New Mexico, the desert sand turned to fused green glass. This

fact, according to the magazine Free World, has given certain

archaeologists a turn. They have been digging in the ancient

Euphrates Valley and have uncovered a layer of agrarian culture

8,000 years old, and a layer of herdsman culture much older, and

a still older caveman culture. Recently, they reached another

layer of fused green glass'.

Egyptian Tektites:

One of the strangest mysteries of ancient

Egypt is that of the great glass sheets that were only

discovered in 1932. In December of that year, Patrick Clayton,

a surveyor for the Egyptian Geological Survey, was driving

among the dunes of the Great Sand Sea near the Saad Plateau in

the virtually uninhabited area just north of the south-western

corner of Egypt, when he heard his tyres crunch on something

that wasn't sand. It turned out to be large pieces of

marvelously clear, yellow-green glass.

In fact, this wasn't just any ordinary

glass, but ultra-pure glass that was an astonishing 98 per

cent silica. Clayton wasn't the first person to come across

this field of glass, as various 'prehistoric' hunters and

nomads had obviously also found the now-famous Libyan Desert

Glass (LDG). The glass had been used in the past to make

knives and sharp-edged tools as well as other objects. A

carved scarab of LDG was even found in Tutankhamen's tomb,

indicating that the glass was sometimes used for jewellery.

An article by Giles Wright in the British

science magazine New Scientist (July 10, 1999), entitled

"The Riddle of the Sands", says that LDG is the purest natural

silica glass ever found. Over a thousand tonnes of it are

strewn across hundreds of kilometres of bleak desert. Some of

the chunks weigh 26 kilograms, but most LDG exists in smaller,

angular pieces--looking like shards left when a giant green

bottle was smashed by colossal forces.

According to the article, LDG, pure as

it is, does contain tiny bubbles, white wisps and inky black swirls. The whitish inclusions consist of refractory minerals such as cristobalite. The ink-like swirls, though, are rich in iridium, which is diagnostic of an extraterrestrial impact such as a meteorite or comet, according to conventional wisdom. The general theory is that the glass was created

by the searing, sand-melting impact of a cosmic projectile.

However, there are serious problems with

this theory, says Wright, and many mysteries concerning this stretch of desert containing the pure glass. The main problem: Where did this immense amount of widely dispersed glass shards come from? There is no evidence of an impact crater of any kind; the surface of the Great Sand Sea shows no sign of a giant crater, and neither do microwave probes made deep into the sand by satellite radar.

Libyan Tektites:

An article entitled "Dating the Libyan Desert Silica-Glass"

appeared in the British journal Nature (no. 170) in

1952. Said the author, Kenneth Oakley.

Pieces of natural silica-glass up to 16 lb in weight

occur scattered sparsely in an oval area, measuring 130 km

north to south and 53 km from east to west, in the Sand Sea of

the Libyan Desert. This remarkable material, which is almost

pure (97 per cent silica), relatively light (sp. gin. 2.21),

clear and yellowish-green in colour, has the qualities of a

gemstone. It was discovered by the Egyptian Survey Expedition

under Mr P.A. Clayton in 1932, and was thoroughly investigated

by Dr L.J. Spencer, who joined a special expedition of the

Survey for this purpose in 1934. Pieces of natural silica-glass up to 16 lb in weight

occur scattered sparsely in an oval area, measuring 130 km

north to south and 53 km from east to west, in the Sand Sea of

the Libyan Desert. This remarkable material, which is almost

pure (97 per cent silica), relatively light (sp. gin. 2.21),

clear and yellowish-green in colour, has the qualities of a

gemstone. It was discovered by the Egyptian Survey Expedition

under Mr P.A. Clayton in 1932, and was thoroughly investigated

by Dr L.J. Spencer, who joined a special expedition of the

Survey for this purpose in 1934.

The pieces are found in sand-free corridors between

north-south dune ridges, about 100 m high and 2-5 km apart.

These corridors or "streets" have a rubbly surface, rather

like that of a "speedway" track, formed by angular gravel and

red loamy weathering debris overlying Nubian sandstone. The

pieces of glass lie on this surface or partly embedded in it.

Only a few small fragments were found below the surface, and

none deeper than about one metre. All the pieces on the

surface have been pitted or smoothed by sand-blast. The

distribution of the glass is patchy.

While undoubtedly natural, the origin of the Libyan

silica-glass is uncertain. In its constitution it resembles

the tektites of supposed cosmic origin, but these are much

smaller. Tektites are usually black, although one variety

found in Bohemia and Moravia and known as moldavite is clear

deep-green. The Libyan silica-glass has also been compared

with the glass formed by the fusion of sand in the heat

generated by the fall of a great meteorite; for example, at

Wabar in Arabia and at Henbury in central Australia.

Reporting the findings of his expedition, Dr Spencer

said that he had not been able to trace the Libyan glass to

any source; no fragments of meteorites or indications of

meteorite craters could be found in the area of its

distribution. He said: "It seemed easier to assume that it had

simply fallen from the sky."

It would be of considerable interest if the time of

origin or arrival of the silica-glass in the Sand Sea could be

determined geologically or archaeologically. Its restriction

to the surface or top layer of a superficial deposit suggests

that it is not of great antiquity from the geological point of

view. On the other hand, it has clearly been there since

prehistoric times. Some of the flakes were submitted to

Egyptologists in Cairo, who regarded them as "late Neolithic

or pre-dynastic".

|