|

Prehistoric Surgery:

(The Ancient Art of Medicine)

Prehistoric Surgery:

(The Ancient Art of Medicine)

On prehistoric brain surgery anatomist Professor Kappers reminisced, "It

is even probable that the trephine holes found in prehistoric skulls 50,000

years old were made for curative purposes".

(Ref:

http://www.time.com )

Featured Items:

Mesopotamian medicine was taken very seriously.

Practitioners were priests and were ruled by the strict laws included

in the code of King Hannurabi. This code, carved on a black stone

eight feet high which was discovered at Shush in what is now Iran in

1901, can be seen today at the Louvre Museum in Paris. At its top can

be seen the emperor Hannurabi receiving the laws from the sun god

Shamash. His code details family law, the rights of slaves, the

penalties for theft and the rewards for success and the severe

punishment for failure on the part of the surgeon. We have evidence

from these writings that surgical conditions such as wounds, fractures

and abscesses were treated. Thus we read:

If a doctor heals a free man's broken limb and

has healed a sprained tendon, the patient is to pay the doctor five

shekels of silver. If it is the son of a nobleman, he will give him

three shekels of silver.

If the physician has healed a man's eye of a

severe wound by employing a bronze instrument and so healed the man's

eye, he is to be paid ten shekels of silver.

If a doctor has treated a man for a severe wound

with a bronze instrument and the man dies and if he has opened the

spot in the mans eye with the instrument of bronze but destroys the

mans eye, his hands are to be cut off.

(2)

Article:

(Dec 18, 2012) Denverpost.com.

'Archaeologists find Prehistoric Humans Cared for Sick and disabled'

Archaeologists have

established that prehistoric people living with congenitally

crippling diseases, making them unable to care for themselves, were

looked after for as long as ten years before their deaths.

Skeletal remains from Vietnam, dating back over 4,000 years show the

unnecessary provision of health care, reflecting some of the most

important aspects of human social culture. Among archaeological

finds there are at least "30 known cases in which the disease or

pathology was so severe, they must have had care in order to

survive". (Quick-link)

Article:

(July 20, 2012) National Geographic.

'Neanderthals Were Self-Medicating'

'A cave in northern Spain

that previously yielded evidence of Neanderthals as brain-eating cannibals now

suggests the prehistoric humans ate their greens and used herbal remedies.

Not only did our extinct cousins prefer grilling vegetables to steaks,

they

were

also

dosing

themselves

with

medicinal

plants,

according

to a

team

led

by

Karen

Hardy,

an

archaeologist

at

the

Catalan

Institution

for

Research

and

Advanced

Studies

in

Barcelona.

The

cave

dwellers'

diet

was

found

to

include

yarrow

and

chamomile,

both

bitter-tasting

plants

with

little

nutritional

value.

"We know that Neanderthals would find these

plants bitter, so it is likely these plants must

have been selected for reasons other than

taste"�probably medication, Hardy said in a

statement. "It fits in well with the

behavioural pattern of self-medication by today's

higher primates, and indeed many other animals."

It's impossible to know what cures

Neanderthals sought from the plants, but people

use them today to treat a variety of ailments,

she noted. "Chamomile is very well known as a herbal

treatment for nerves and stress, and for

digestive disorders," while yarrow is used to

treat colds and fevers and works as an

antiseptic, she said'

(Quick-link)

Article: (Oct, 2007), 'Nature Proceedings'.

'Neolithic France; The Earliest Amputation'.

Scientists

unearthed evidence of the surgery during work on an Early Neolithic

tomb [4900-4700 BC] discovered at Buthiers-Boulancourt, about 40

miles (65km) south of Paris. They found that a remarkable degree of

medical knowledge had been used to remove the left forearm of an

elderly man about 6,900 years ago. The patient seems to have been

anaesthetised, the conditions were aseptic, the cut was clean and

the wound was treated, according to the French National Institute

for Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap).

The revelation could force a reassessment of the history of surgery,

especially because researchers have recently reported signs of two

other Neolithic amputations in Germany [Sondershausen in eastern

Germany] and the Czech Republic [Vedrovice,

in Moravia]. It was known that Stone

Age doctors performed trephinations, cutting through the skull, but

not amputations. �The first European farmers were therefore capable

of quite sophisticated surgical acts,� Inrap said. The discovery was

made by C�cile Buquet-Marcon and Anaick Samzun, both archaeologists,

and Philippe Charlier, a forensic scientist.

It followed research on the tomb of an elderly man who lived in the

Linearbandkeramik period, when European hunter-gatherers settled

down to agriculture, stock-breeding and pottery. The patient was

important: his grave was 2m (6.5ft) long � bigger than most � and

contained a schist axe, a flint pick and the remains of a young

animal, which are evidence of high status.

The most intriguing aspect, however, was the absence of forearm and

hand bones. A battery of biological, radiological and other tests

showed that the humerus bone had been cut above the trochlea indent

at the end �in an intentional and successful amputation�. Mrs

Buquet-Marcon said that the patient, who is likely to have been a

warrior, might have damaged his arm in a fall, animal attack or

battle.

�I don�t think you could say that those who carried out the

operation were doctors in the modern sense that they did only that,

but they obviously had medical knowledge,� she said. A flintstone

almost certainly served as a scalpel. Mrs Buquet-Marcon said that

pain-killing plants were likely to have been used, perhaps the

hallucinogenic Datura. �We don�t know for sure, but they would have

had to find some way of keeping him still during the operation,� she

said.

Other plants, possibly sage, were probably used to clean the wound.

�The macroscopic examination has not revealed any infection in

contact with this amputation, suggesting that it was conducted in

relatively aseptic conditions,� said the scientists in an article

for the journal Antiquity. The patient survived the operation and,

although he suffered from osteoarthritis, he lived for months,

perhaps years, afterwards, tests revealed. Despite the loss of his

forearm, the contents of his grave showed that he remained part of

the community. �His disability did not exclude him from the group,�

the researchers said. The discovery demonstrates that advanced

medical knowledge and complex social rules were present in Europe in

about 4900 BC, and that major surgery was likely to have been more

common than we realised, Mrs Buquet-Marcon said. (3)

|

Trepanning: Prehistoric Brain Surgery: |

Trepanation is perhaps the oldest surgical procedure for which there

is evidence, and in some areas may have been quite widespread.

An ancient site in Ishtikunuy, located near Lake Sevan,

in Armenia yielded two particular skulls from approx' 2,000 BC that showed evidence of

head surgery. The first was he skull of a woman with a head injury which

made a hole a quarter of an inch wide. A plug of animal bone had been

inserted in its place. The fact that the woman survived was evident from the

cranial growth around the plug before she died. The second skull as another

woman, who had had a blunt object that had splintered the inner layers of

the cranial bone. The 'Surgeon' cut a larger hole around the puncture and

removed the splinters. Evidence shows that she survived another 15 years.

Obsidian razors have been found at the site that are still sharp enough to

be used today. (9)

The well-preserved

skull of Gadevang Man, a prehistoric 'bog body', dated 480-60 BC, found

in Denmark (Left). The skull shows signs of surgical trepanning.

The precise cuts that can be seen on some of the

trephined skulls, and the re-growth of the bone (which proves that the

patient/victim survived the operation), indicate that prehistoric

people had the ability and knowledge to be

successful surgeons.

"This operation involves the removing of one

or more parts of the skull without damaging the blood vessels, the

three membranes that envelope the brain � the dura matter, pia mater

and arachnoid � or the actual brain; not surprisingly, it is a

procedure that requires both skill and care on the part of the

surgeon" (Rudgely 1999, p-126).

Out of 120 prehistoric skulls found at

one burial site in France dated to 6500 BC, 40 had trepanation holes.

Surprisingly, many prehistoric and pre-modern patients had signs of

their skull structure healing; suggesting that many of those that

proceeded with the surgery survived their operation.

(1)

Extract: 'Archaeologists have found

trepanned skulls dating from the late Neolithic, some 5,000 years

ago. Now a team of French and German researchers has suggested

that the procedure goes back even further, to at least 7,000 years

ago.

The evidence comes from the French village of Ensisheim. To date,

archeologists there have unearthed 45 graves containing 47

individuals. One grave held the remains of a 50-year-old man who

had two holes in his skull. Both holes were remarkably free of

surrounding cracks and were clearly the result of surgery, not

violence. One hole, in the frontal lobe, is about 2.5 inches wide;

the second, at the top of the skull, is about an inch wider.

Most questionable trepanations are rather small, and with some you

cannot tell the shape of the original hole that was made within

the skull, or whether it was a fracture, says archaeologist Sandra

Pichler of Freiburg University in Germany, a member of the team.

But in our case you can still see the very straight, slanting

edges of the larger trepanation, and this is artificial. There is

no natural explanation for a hole like that.

Both holes had time to heal before the man died--the smaller hole

is completely covered over with a thin layer of bone; the larger

is roughly two-thirds covered--and neither shows signs of

infection. So they must have had a very good surgeon, and there

must have been some way or another of avoiding infection, Pichler

says. Pichler and her colleagues estimate that it would take at

least six months, and perhaps as much as two years, for such

extensive healing. Since the two holes did not heal to the same

degree, it�s likely they were made during two separate operations.

The team doesn�t know why the man was operated on. Nor can they be

sure exactly how the trepanations were performed, although the cut

marks indicate that the bone was removed by a mixture of cutting

and scraping. Stone Age tools were certainly up to the task: flint

knives are actually sharper than modern scalpels.

The trepanations were done so perfectly that this can�t be the

oldest one, Pichler says. They must have practiced somehow, and

the knowledge of how to do this kind of operation must have been

passed down, Pichler says. The fact that there are two

trepanations is further corroboration: if there had been just one,

you could say that they were lucky. But if you survived two such

operations, your surgeon must have known what he was doing'.

Ref:

http://discovermagazine.com

Trepanation

in the Indus Valley culture: The skull on the right was found in a

Harrapan setting, circa 4,000 B.P. The link below leads to

fascinating article describing a Neolithic skeleton with multiple-trepanated

skull found in Kashmir, the archaeological circumstances of the find,

the dating, the background, the skeletal evidence, the details of the

trepanation and possible affiliations to the Indus civilization. It

speculates briefly about possible medical grounds for the surgery. Trepanation

in the Indus Valley culture: The skull on the right was found in a

Harrapan setting, circa 4,000 B.P. The link below leads to

fascinating article describing a Neolithic skeleton with multiple-trepanated

skull found in Kashmir, the archaeological circumstances of the find,

the dating, the background, the skeletal evidence, the details of the

trepanation and possible affiliations to the Indus civilization. It

speculates briefly about possible medical grounds for the surgery.

Ref:

http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/reprints/sankhyan/burzahom.htm

|

Open Heart Surgery.

The

Soviet Academy of Sciences announced in 1969 that a number of ancient

skeletons, found in central Asia showed signs of surgery having been

performed in the area of the heart. Every feature corresponded to what

today is called a 'Cardiac Window', enabling surgeons to perform open

heart surgery.

(9)

|

Article (April,

2012): Beeswax as

Dental Filling on a Neolithic Human Tooth

The finding of a human 6,500 year old partial mandible

associated with contemporary beeswax covering the occlusal

surface of a canine, could represent a possible case of

therapeutic use of beeswax during the Neolithic period in

Slovenia. Although the possibility of treatment of sensitive

tooth structure by means of some type of filling has been

supposed, there is no other published evidence on the use of

therapeutic-palliative substances in prehistoric dentistry. In

ancient Egypt, external applications, composed of honey mixed

with mineral ingredients, were used to fix loose teeth or to

reduce the pain, as reported in the Papyrus Ebers, dating back

to the XVI century BC. (Source:

http://www.plosone.org)

Article: MSNBC (2006) - Proving

prehistoric man�s ingenuity and ability to withstand and inflict

excruciating pain, researchers have found that dental drilling dates

back 9,000 years.

Primitive dentists

drilled nearly perfect holes into live but undoubtedly unhappy patients

between 5500 B.C. and 7000 B.C., an article in Thursday�s issue of the

journal Nature reports.

Researchers carbon-dated at least nine skulls with 11 drill holes found

in a Pakistan graveyard.

That means dentistry is

at least 4,000 years older than first thought � and far older than the

useful invention of anaesthesia.

(Ref:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12168308/)

(Extract from 'THE TIMES', Thurs April 12th 2001).

Prehistoric dentists may have been using stone drills to treat tooth decay

up to 9,000 years ago, a team of archaeologists has discovered.

Excavations at a site in Pakistan have unearthed skulls containing teeth

dotted with tiny, perfectly round holes. Under an electron microscope,

they revealed a pattern of concentric grooves, that were almost certainly

formed by the circular motion of a drill with a stone bit.

The

discovery, which was made at an archaeological dig in Mehrgarh, in

Baluchistan Province, offers the earliest evidence of human dentistry.

The

excavated village belonged to a civilisation that thrived between 8,000 and

9,000 years ago, whose members cultivated crops and made jewellery from

shells, amethyst and turquoise.

Andrea

Cucina, of the University of Missouri-Columbia, who found the molars with

telltale marks, said: �At this point we can�t be certain, but it is very

tantalising to think they had such knowledge of health and cavities and

medicine to do this�.

Dr

Cucina, whose research is reported in New Scientist magazine, said the

holes would probably have been filled with some sort of medicinal herb to

treat tooth decay. Any filling would long ago have decomposed.

The

dental discovery was made while Dr Cucina was washing teeth from the

Mehrgarhing and spotted the tiny hole in the biting surface of a molar.

The hole was too perfectly round to have been caused by bacteria and the

tooth had been found in a jawbone, ruling out the possibility that it had

been pierced to be strung on to a necklace.

The Top

of the hole was rounded from chewing, suggesting that it was made while

the owner was still alive.

(Examples

of Prehistoric Drilling)

|

Prehistoric Egyptian Surgery: |

In ancient Egyptian medicine the skills and

knowledge of doctors developed from the legacy of the prehistoric

age. Doctors in ancient Egypt were usually also priests, and

religious rituals continued to be used alongside rational

treatments as both were believed necessary for a cure. Important

deities invoked in medicine included Imhotep, the god of healing,

who was formerly doctor to Pharaoh Zoser in the 3rd millennium

BC, and Thoth, god of wisdom and learning.

A system of medical training was established in the temples and a

written language developed using hieroglyphics. Medical treatments

were recorded on papyri such as the Papyrus Ebers and the Papyrus Edwin Smith. The standard work used by Egyptian

doctors was the Book of Thoth, a collection of ritual and

rational treatments. The religious practice of mummification, in

which the organs of the body were removed, helped Egyptian doctors

to gain an understanding of human anatomy, although dissection was

banned for religious reasons. However, Egyptian doctors began to

practise basic surgery such as the removal of growths on the skin

or cataracts from the eyes. Egyptian doctors believed that illness

was often caused by the body's channels becoming blocked because

of rotting food in the stomach, a practical theory based on their

observation of the River Nile. Patients affected were given

emetics to make them vomit or laxatives to loosen their bowels and

clear the blockage.

Ref:

http://encyclopedia.farlex.com

Article: (Oct, 2012) - 'MessageToEagle.com'.

'Evidence of

Sophisticated Prosthetics in Ancient Egypt'

'In

1996, scientists discovered that the 2600-year-old mummy of an

Egyptian priest Usermontu in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum

drew a worldwide attention when an x-ray revealed an ancient

nine-inch metal screw connecting the mummy's thigh and lower

leg. And according to Dr. Richard Jackson, orthopedic surgeon

for BYU's athletic team, the pin was made with a lot of

biomechanical things we still use to make sure we get good

fixation in stabilizing bone! Now, the results of scientific

tests using replicas of two ancient Egyptian artificial toes,

including one that was found on the foot of a mummy, suggest

that they�re likely to be the world�s first prosthetic body

parts'.

Images of 2600

year old Egyptian surgical screw (left) and prosthetic toe (right).

(Link

to Full Article)

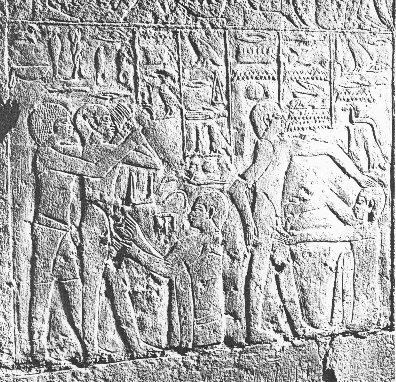

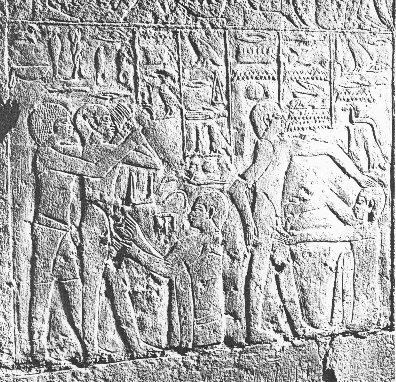

Circumcision:

Circumcision might

well be claimed to be the most ancient 'elective' operation and was

practiced in Ancient Egypt by assistants to the priests on the priests

and on members of Royal Families. There is remarkable evidence for

this carved on the tomb of a high ranking royal official which was

discovered in the Saqqara cemetery in Memphis and is dated between

2400 and 3000 BC.

This represents two

boys or young men being circumcised. The operators are employing a

crude stone instrument. While the patient on the left of the relief is

having both arms held by an assistant, the other merely braces his

left arm on the head of his surgeon. The inscription has the operator

saying 'hold him so that he may not faint' and 'it is for your

benefit'. (2)

(Ancient

Egypt Homepage)

|

Trepanation

in the Indus Valley culture: The skull on the right was found in a

Harrapan setting, circa 4,000 B.P. The link below leads to

fascinating article describing a Neolithic skeleton with multiple-trepanated

skull found in Kashmir, the archaeological circumstances of the find,

the dating, the background, the skeletal evidence, the details of the

trepanation and possible affiliations to the Indus civilization. It

speculates briefly about possible medical grounds for the surgery.

Trepanation

in the Indus Valley culture: The skull on the right was found in a

Harrapan setting, circa 4,000 B.P. The link below leads to

fascinating article describing a Neolithic skeleton with multiple-trepanated

skull found in Kashmir, the archaeological circumstances of the find,

the dating, the background, the skeletal evidence, the details of the

trepanation and possible affiliations to the Indus civilization. It

speculates briefly about possible medical grounds for the surgery.