|

Navigation:

(Prehistoric Methods of Navigation)

Navigation:

(Prehistoric Methods of Navigation)

Navigation Methods

in Prehistory.

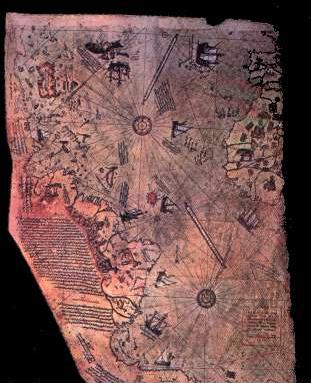

Potentially one of the most

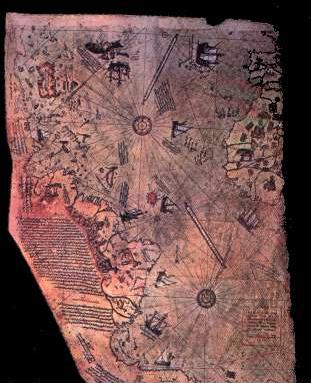

significant finds in modern time. The Piri-reis map (right) shows both the

American coastline and demonstrates the early use of longitude and latitude.

The key to the map states that sections of it originate

from the time of Alexander the Great, a statement which clearly suggests

that such knowledge was available at that time.

(More

about the Piri-reis map)

In addition to this, there are several other solid pieces of evidence that demonstrate

the existence of a set of navigational skills existed in prehistory

as the following examples show:

|

Navigation in Prehistory: |

Navigation from one location to another relies on a means of

calculating direction. The following methods are some of the better

known methods.

Cellestial navigation:

Probably the oldest form of navigation is that carried out

with the use of the

stars at night, and the sun during the day. This form of navigation

requires a simple knowledge of the movement of the heavens. For example:

-

Both the sun and the moon can be used

to determine direction.

-

Polaris is a good indicator of north.

-

Polaris can be used to

determine latitude.

-

Observation of eclipses can

determine longitude.

The Phoenicians looked to the heavens. The sun moving across the commonly

cloudless Mediterranean sky gave them their direction and quarter. The

quarters we know today as east and west the Phoenicians knew as Asu

(sunrise) and Ereb (sunset), labels that live today in the names Asia and

Europe.

Ley-lines: In

his book, The long Straight Track, Alfred Watkins proposed that ley-lines

were used by prehistoric people as to travel along for trade amongst other

uses. Stones and other significant monuments were placed along their length.

Peruvian straight-lines have the same function, as do the Aboriginal

Tuaringas in Australia.

(More about Leylines)

Magnetism: Certain

animals such as pigeons are known to use the earths magnetic field for

navigation, the extraordinary navigational skills of birds have been

recorded for millennia, and could well have been applied as a navigational

aid.

1 ,000 B.C.

-

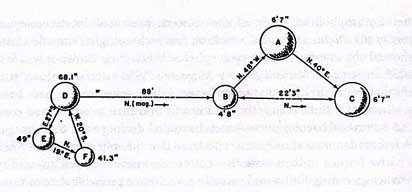

It has been established that

this object (34 x 9 x 4mm), was part of a larger bar. It has been polished

on each face, and has a groove running 'approximately and possibly

intentionally parallel to the edges' along one of the flattened-faces.

If its function was to serve as a directional finder (as is commonly

supposed), the longer its original length, the more accurate the reading

would have been. Under experiment, it repeatedly provided a consistent

bearing (to within 1/2�), using a 'stadia-rod' at 30m.

This naturally magnetic square metal fragment (M-160)

points 35.5� West of magnetic

North (when made to float). It was found in an Olmec mound in Vera Cruz,

Mexico.

Several examples of naturally magnetised statues

have been found at other south American sites, noticeably in

Guatemala where carvings of figurines and animals were designed with

the magnetised sections in the navels and temples of the figures.

How such magnetic properties were first identified in the stone

remains a mystery.

(More about Magnetism in

Prehistory)

The Chinese Navigators.

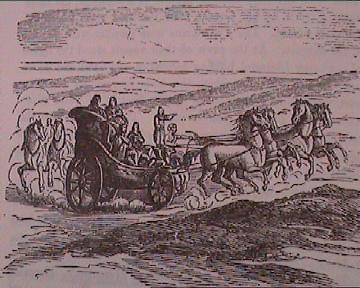

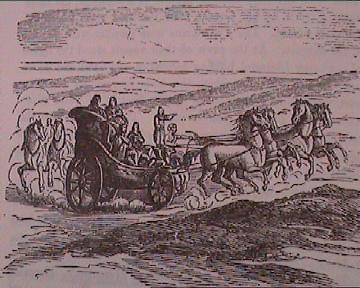

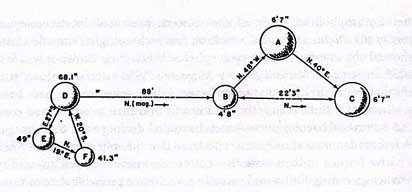

The above is a Chinese invention which

through a system of gears always pointed the direction �home�. The little

sage atop the centre post points toward the origin of the journey no matter

how many turns and changes in direction the cart has taken�

2,000 B.C

- 'Emperor Wang-Ti

placed magnetic figures with an extendable arm to the front of carriages.

Apparently they pointed South'. (Ref: Ignatius Donnelly: Atlantis) 2,000 B.C

- 'Emperor Wang-Ti

placed magnetic figures with an extendable arm to the front of carriages.

Apparently they pointed South'. (Ref: Ignatius Donnelly: Atlantis)

The similarity between the two objects

described suggests that they are both one and the same.. which description

is correct is a matter of conjecture.

( More

about Prehistoric China)

(More about Magnetism in

prehistory)

Navigation at sea:

The

first seafarers kept in sight of land; following the coast. One could line

up landmarks, such as a rock against a distant point on land; doing that in

two directions at once gave a more or less precise geometric location on the

surface of the sea. Sounding using a lead and line also helped. "When you

get 11 fathoms and ooze on the lead, you are a day's journey out from

Alexandria," wrote Herodotus in the fourth century B.C. The Greeks even

learned to navigate from one island to the next in their archipelago, a

Greek word meaning "pre�minent sea". They may have followed clouds (which

form over land) or odours (which can carry far out to sea).

"Crete is believed to have been colonized by migrant farmers from

Anatolia as early as the eighth or seventh millennium B.C., although

hunter-gatherers surely landed there earlier. Broodbank and Strasser

have shown that the colonization of this island must have been

deliberate and that a minimum number of people and livestock were

required to sustain its initial population� The earliest human

presence is recorded at stratum X at Knossos, almost two thousand

years before any other human presence in the Aegean� the distances are

significant and certainly entailed the usage of stars for orientation

at night�thus it is not surprising that seafaring, including

navigation and its offshoot, astronomy, took root here very early�.

(D. Davis. 2001)

The

Piri-Reis map: Potentially one

of the most significant finds in

modern time. The Piri-reis map (c. 1513), shows the coastlines of the American continent. It also includes the outline of the Antarctic

continent which has been frozen over since around 4,000 BC. This map alters all

previous conceptions of our pre-historic ancestors abilities. The 'Piri-Reis' map (c.

1513). is one of several 'portellano's', which appear to have a

geometric basis of unknown provenance. This map has many

interesting features, such as:- The

Piri-Reis map: Potentially one

of the most significant finds in

modern time. The Piri-reis map (c. 1513), shows the coastlines of the American continent. It also includes the outline of the Antarctic

continent which has been frozen over since around 4,000 BC. This map alters all

previous conceptions of our pre-historic ancestors abilities. The 'Piri-Reis' map (c.

1513). is one of several 'portellano's', which appear to have a

geometric basis of unknown provenance. This map has many

interesting features, such as:-

The map has

pre-Columbian provenance.

The map shows the coastline of America.

The map shows accurate use of

Longitude and Latitude.

The map-builders used 'Spherical geometry'.

The centre of the map is at

the junction of the 23.5˚

parallel and the longitude of Alexandria.

The cartographers of the Piri-reis map used a system called the

12-wind system, which was used extensively in the middle ages and has

its roots in the Babylonian sciences.

(More

about the Piri-reis map)

Polynesian Navigation:

Heeding

the flight-paths of birds was just one of numerous haven-finding methods

employed by the Polynesians, whose navigational feats arguably have never

been surpassed. The Polynesians travelled over thousands of miles of

trackless ocean to people remote islands throughout the southern Pacific.

Like Eskimos study the snow, the Polynesians watched the waves, whose

direction and type relinquished useful navigational secrets. They followed

the faint gleam cast on the horizon by tiny islets still out of sight below

the rim of the world. Seafarers of the Marshall Islands built elaborate maps

out of palm twigs and cowrie shells. These ingenious charts, which exist

today only in museums, denoted everything from the position of islands to

the prevailing direction of the swell.

This massive statue from

Easter island was buried up to the chest. When uncovered it revealed this

image of a sailed ship.

The ancient Polynesians

navigated their canoes by the stars and other signs that came from the ocean

and sky. Navigation was a precise science, a learned art that was passed on

verbally from one navigator to another for countless generations.

In 1768, as he sailed from Tahiti, Captain Cook had an additional passenger

on board his ship, a Tahitian navigator named Tupaia. Tupaia guided Cook 300

miles south to Rurutu, a small Polynesian island, proving he could navigate

from his homeland to a distant island. Cook was amazed to find that Tupaia

could always point in the exact direction in which Tahiti lay, without the

use of the ship's charts. Sadly, Cook was never able to learn and document

Tupaia's navigational techniques, for Tupaia, and many of Cook's crew, died

of malaria in the Dutch East Indies. Unlike later visitors to the South

Pacific, Cook understood that Polynesian navigators could guide canoes

across the Pacific over great distances.

But these navigational skills, along with the double canoe, disappeared with

the emergence of Western technology, which mariners the world over came to

rely on. In 1976, the Hokule'a', a replica Polynesian double canoe made by a

team of Hawaiian canoeists, voyaged from Hawaii to Tahiti using the ancient

navigational techniques of their ancestors. Ben Finney, a member of the

team, explains their mission: "Since by the 1960s Polynesian voyaging canoes

had disappeared and ways of navigating without instruments had largely been

forgotten, those of us who objected to Heyerdahl's ...negative

characterizations of Polynesian voyaging technology and skills ...concluded

that we would have to reconstruct the canoes and ways of navigating, and

then test them at sea, in order to get at the truth."

Using no instruments, the canoe team navigated as their ancestors did, by

the stars. They had no maps, no sextants, no compasses, and navigated by

observing the ocean and sky, reading the stars and swells. The paths of

stars and rhythms of the ocean guided them by night and the colour of sky and

the sun, the shapes of clouds, and the direction from which the swells were

coming, guided them by day. Several days away from an island, they were able

to determine the exact day of land fall. Swells would tell them that there

was land ahead, and the surest telltale sign would be the presence of birds

making flights out to sea seeking food. By sailing from Hawaii to Tahiti,

Hokule'a's team was able to prove that it was possible for Polynesian

peoples to migrate over thousands of miles from island to island.

(The

Prehistoric Pacific)

Article: Possible Prehistoric Navigation

Tools (06-Oct-2001)

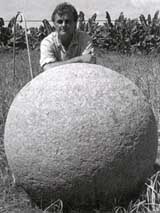

On

Dreamland September 6, 2001, Ivar Zapp and George Erikson discuss a

remarkable new theory of ancient navigation that is based on a group of

mysterious stone spheres in Costa Rica. The alignment of these spheres

implies the existence of a complex and world-girdling navigation system

that must date from very ancient times. On

Dreamland September 6, 2001, Ivar Zapp and George Erikson discuss a

remarkable new theory of ancient navigation that is based on a group of

mysterious stone spheres in Costa Rica. The alignment of these spheres

implies the existence of a complex and world-girdling navigation system

that must date from very ancient times.

The spheres themselves have been described by

archaeologists as "out of context," meaning that they do not fit

established patterns of construction and architecture seen in the area. No attempt has ever been made to explain

them or date them.

architecture seen in the area. No attempt has ever been made to explain

them or date them.

Zapp and Erikson, however, have studied not only these

spheres, but enigmatic ruins around the world, and are proposing a theory

that they are the totally unexpected but very sophisticated navigational

tools.

(5)

Viking Navigation

The Norsemen had to have

other navigational means at their disposal, for in summer the stars

effectively do not appear for months on end in the high latitudes. One

method they relied on was watching the behaviour of birds. A sailor wondering

which way land lay could do worse than spying an auk flying past. If the

beak of this seabird is full, sea dogs know, it's heading towards its

rookery; if empty, it's heading out to sea to fill that beak. One of the

first Norwegian sailors to hazard the voyage to Iceland was a man known as

Raven-Floki for his habit of keeping ravens aboard his vessel. When he

thought he was nearing land, Raven-Floki released the ravens, which he had

deliberately starved. Often as not, they flew "as the crow flies" directly

toward land, which Raven-Floki would reach simply by following their lead.

Article:

Mail-Online (November, 2011) Norse Navigators may have

located the sun with crystal Feldspar.

'Ancient legends

of Viking mariners using mysterious sunstones to reveal the position

of the sun on a cloudy day may well be true, according to a new

study. While experts have long argued that Vikings knew how to use

blocks of light-fracturing crystal to locate the sun through dense

clouds, archaeologists have never found solid proof. Vikings, they

argue, used transparent calcite crystal - also known as Iceland spar

- to fix the true bearing of the Sun to within a single degree of

accuracy. The naturally occurring stone has the capacity to

'depolarise' light, filtering and fracturing it along different

axes, the researchers explained. The recent discovery of an Iceland

spar aboard an Elizabethan ship sunk in 1592 - tested by the

researchers - bolsters the theory that ancient mariners were aware

of the crystal's potential as an aid to navigation. Even in the era

of the compass, crews might have kept such stone on hand as a

backup, the study speculates. 'We have verified that even only one

of the cannons excavated from the ship is able to perturb a magnetic

compass orientation by 90 degrees,' the researchers wrote. 'So, to

avoid navigation errors when the Sun is hidden, the use of an

optical compass could be crucial even at this epoch, more than four

centuries after the Viking time.' The study appeared in Proceedings

of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences, a

peer-reviewed journal published by Britain's de facto academy of

science, the Royal Society.'

(4)

(More

about Crystal use in Prehistory)

|

2,000 B.C

- 'Emperor Wang-Ti

placed magnetic figures with an extendable arm to the front of carriages.

Apparently they pointed South'. (Ref: Ignatius Donnelly: Atlantis)

2,000 B.C

- 'Emperor Wang-Ti

placed magnetic figures with an extendable arm to the front of carriages.

Apparently they pointed South'. (Ref: Ignatius Donnelly: Atlantis)

On

Dreamland September 6, 2001, Ivar Zapp and George Erikson discuss a

remarkable new theory of ancient navigation that is based on a group of

mysterious stone spheres in Costa Rica. The alignment of these spheres

implies the existence of a complex and world-girdling navigation system

that must date from very ancient times.

On

Dreamland September 6, 2001, Ivar Zapp and George Erikson discuss a

remarkable new theory of ancient navigation that is based on a group of

mysterious stone spheres in Costa Rica. The alignment of these spheres

implies the existence of a complex and world-girdling navigation system

that must date from very ancient times.  architecture seen in the area. No attempt has ever been made to explain

them or date them.

architecture seen in the area. No attempt has ever been made to explain

them or date them.