|

The Piri-Resi Map:

(Prehistoric Cartography)

The Piri-Resi Map:

(Prehistoric Cartography)

|

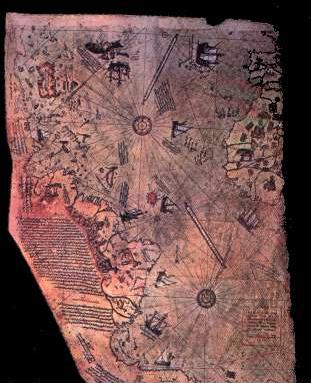

P otentially one

of the most significant finds of

modern time as it is clearly dated 1513 AD and shows both the coastlines of the American and

debatably, the Antarctic coastline (which has been frozen over since around 4,000 BC). This map alters all

previous conceptions of our pre-historic ancestors abilities. The 'Piri-Reis'

map is one of several 'portellano's' which appear to have a

geometric basis of unknown provenance. It has several

interesting features which deserve investigation, such as:-

The map has

pre-Columbian provenance.

The map shows the coastline of America.

The map shows accurate use of

Longitude and Latitude.

The map-builders used 'Spherical geometry'.

The map centres at

the junction of the 23.5˚

parallel (Tropic of cancer), and the longitude of Alexandria.

|

|

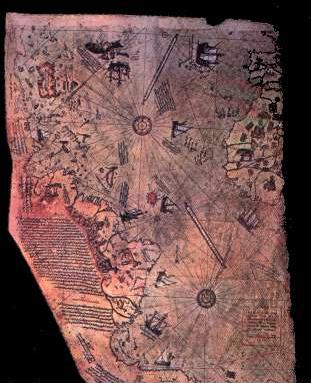

In 1929, a section of a world map drawn by the Turkish Admiral Reis

(Piri-reis), was found in the basement of a museum in

Constantinople. The map was of immediate interest as it appeared to

show the coastlines of South America and Africa at their correct

relative longitudes and latitudes, and the legend on the map dated

it to 'Muharran' in the Moslem year 919 (1513 AD), only 20

years after the official discovery of the Americas by Columbus in

1492. The legend on the map itself however, gave it an origin far

older than 20 years, revealing that it was a section of a world map

composed from more than twenty source maps, some drawn in the time

of Alexander the great, and that 'some were based on

mathematics'

(4).

The fact that there was no known means of accurately calculating

longitude in 1513 AD led Prof. Charles Hapgood to examine the map

further.

Hapgood's research led him to make several fundamental conclusions;

Firstly, he confirmed that the coastlines of the continents had been

accurately plotted with regards to both latitude and

longitude. Secondly, he determined that the co-ordinates had

been mathematically converted from natures spherical model to fit

the two dimensional representation of a map, (a method similar in

principle to Mercator�s projection). Thirdly, he showed that a

connection existed between this map and several other ancient

portolano�s and mappa-mundi, some of which included the

outline of the Antarctic continent.

These facts led Hapgood to suggest the existence of a set of

knowledge from a time before the Greeks, and placed a question mark

over the origin of sciences such as geometry, geography and

cartography, traditionally accredited to the Greeks.

The presence of a Mercatorial projection on such old maps is

significant as such high levels of geometry had not been seen since

the time of the Greeks and it was not until the work of Gerald

Mercator in 1569, that European�s began to include a

projection for the curvature of the earth into their maps. We can be

fairly sure that the inclusion of such a projection was not the work

of Piri-reis, as he left several cartographic errors of his own

(such as skewed sections of coastline, and the duplication of

the Amazon river), which testified to the fact that the Piri-reis

map is actually a montage of other maps, and he admitted

himself that his world map was �composed with the use of other

source-maps' which therefore already included the

projection. An association of such knowledge even as far back as

the Greeks, is in itself, an achievement worthy of merit.

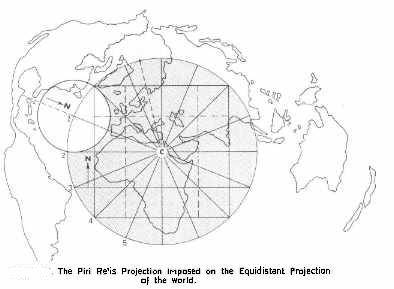

We can see that the horizontal lines on the map are geographically

(and astronomically) significant, with the Equatorial line sitting

correctly between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, both of which

are also marked with �Rose des vents�. The inclusion of

vertical lines marking the correct longitudinal separation between

the African and South American continents identifies the map as

having a cylindrical projection, a feature which is not seen

on maps before this time, or for another fifty years until Mercator

presented his map to the world. This identification of the Tropics

within the geometry of the map confirms the suspicion that a

knowledge of astronomy was available to the original cartographer,

who also used the Tropic of Cancer to mark the geographic centre of

the map

(4).

The calculation of latitude is a relatively easy procedure requiring

only a single observation of the height of the sun from the horizon,

the length of a shadow or the height of the pole star in the sky,

whereas the calculation of longitude is a more complicated

figure to deduce. It is because of this that off-shore navigation

was for a long time at best educated guesswork (dead-reckoning),

a situation which became an anathema to the European scientific

community for several hundred years, managing to elude some of the

greatest scientific minds of the time (Galileo and Newton included),

and it was not until 1760 that success was eventually realised in

the shape of a precision ships-clock or chronometer, and

world maps were re-charted accurately, and apparently for the

first time. The development of such a timepiece meant that if a

sailor reset a ships-clock at noon each day, and compared the

difference between that clock and another unadjusted clock from a

known longitude, the difference between the two could be translated

into longitude (as each four minutes of difference between the two

clocks translates into a single degree of longitude).

Apart from the possible exception to the Antykithera find, which may

have functioned as an �astrolabe', the Greeks were known to

have calculated longitude with the use of astronomy, as did several

other cultures in history. A record from 14th century

China states that �Wang Da Yuan achieved a transoceanic passage

from Mozambique to Sri Lanka using a combination of compass and star

linked positions called gouyang Qianxing to determine latitude and

longitude�

(28).

We know that this level of astronomy was not generally available in

the west, and a workable means of calculating longitude was

apparently still not known in

Europe

at 1540 AD, when the German astronomer Johanes Werner first proposed

using the moon as a location indicator

(19). (If

an eclipse is predicted at a location at a certain time and one

experiences the eclipse an hour earlier, then one knows that they

are positioned 15 degrees east of their original location). While

this system works well in the presence of an eclipse, their

infrequency makes them impracticable as a method for sailors to use

�on demand�, and relies on an accurate reading of the time of

eclipse at both locations.

Apart from the fact that the map is dated at 1513 AD, long before

the discovery of such an accurate method of calculation, Piri-reis

himself states in the legend that it was a composite of several

older maps, including some drawn �in the days of Alexander, Lord

of the Two Horns..�, some ��Arabic Jaferiyes�� and one

�...drawn by Columbo in the western region�. With regards this

latter contribution from Columbus, he adds that ..

��it is reported thus, that a Genoese infidel, his name was Columbo,

who discovered these places. For instance, a book fell into the

hands of the said Columbo, and he found it said in this book that at

the western end of the Western sea (Atlantic) that is, on its

western side, there were coasts and islands and all kinds of metals

and precious stones. Columbo having studied this book thoroughly,

explained these matters one by one to the Greats of Genoa��

(4).

We therefore have several suggestions that this map at least,

includes a set of knowledge that predates the European renaissance

of the sciences which followed the intellectual vacuum of the

�Dark-ages� under the shadow of the �Holy church of Rome� (a time

when science was rejected as witchcraft and the world was believed

flat). If it is the case that all the continents of the world were

accurately charted onto a world map before this time, it would be an

historic achievement and worthy of recognition in its own right, and

it is the very presence of one of the continents that has generated

the most debate. The coastline of the Antarctic continent appears

accurately on several ancient maps although it has

been covered by several miles of ice-pack from a time long before

the Greek empire and the first officially recognised world map by

Ptolemy in 150 AD.

(19).

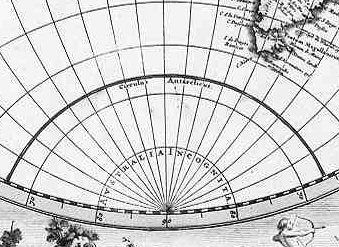

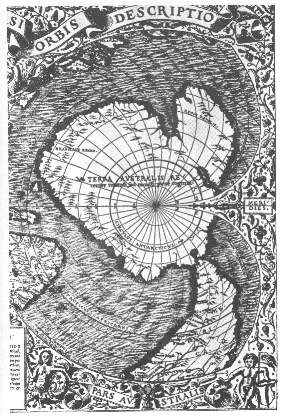

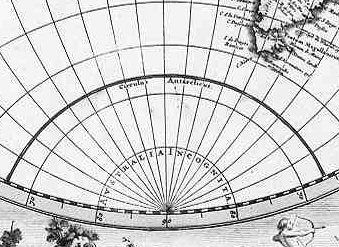

'Terra Australis Incognita'

The Antarctic coastline (Terra Australis Incognita):

The recognition of the Antarctic continent on certain ancient

world-maps may well turn out to be Hapgood�s most significant

discovery as, apart from the fact that there is no record of anyone

ever having charted the continent, it is a feat said by geologists

to have been last physically possible only through a window of

opportunity between 10,000 BC and 4,000 BC

(4),

a date that was arrived at through analysis of core samples taken

from the Ross sea-bed, which established that sub-tropical flora and

fauna were present on Antarctica during these dates, and following

which a severe climatic shift resulted in the region freezing over.

The conclusion of this fact is that the cartographers of the map

would have had to have charted that region no later than 4,000 BC, (before

the coastline froze over). The recognition of the Antarctic continent on certain ancient

world-maps may well turn out to be Hapgood�s most significant

discovery as, apart from the fact that there is no record of anyone

ever having charted the continent, it is a feat said by geologists

to have been last physically possible only through a window of

opportunity between 10,000 BC and 4,000 BC

(4),

a date that was arrived at through analysis of core samples taken

from the Ross sea-bed, which established that sub-tropical flora and

fauna were present on Antarctica during these dates, and following

which a severe climatic shift resulted in the region freezing over.

The conclusion of this fact is that the cartographers of the map

would have had to have charted that region no later than 4,000 BC, (before

the coastline froze over).

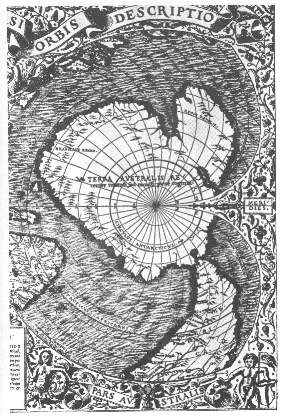

The presence of the Antarctic continent on the Piri-reis map

is in debate, with suggestions that the bottom tip of the south

American continent was simply �squeezed� on, following a

miss-judgment in size by Piri-reis. Regardless of this, there are

other ancient maps which clearly do have the outline of the

continent on them, with both Gerard Mercator's map of 1569 AD

and the Oronteus Finaeus map of 1532 AD (right), also showing the

coastline, and the Hadji Ahmed map of 1559 AD, which not only

has Antarctica with a correct Mercatorial projection but also shows

a land bridge between the Bering straits, re-enforcing the

suggestion of an antiquitous origin. The specific division of the

Antarctic continent into two smaller land-masses on these ancient

maps is similarly a mystery as it was only at the end of the 20th

century that we were finally able to determine (through satellite

technology) the accurate outline of the Antarctic continent, which

was found to be identical to those seen on some of the oldest

surviving maps of the world.

Hapgood�s research led him to identify another feature common to

several ancient maps which was that the Antarctic continent

occasionally appears greatly enlarged with details along the

coastline remaining consistent to scale. It was through this

particular finding that Hapgood realised that the line called the 'Circulus

Antarcticus' which appears on maps at this time was the same as

the 80th parallel on modern maps (made with a Mercatorial

projection), and he suggested from this that the original maps had

been made with a Mercatorial projection and divided into units of 10

degrees from a division of the globe into 360�, he then concluded

that this original map was then later copied without realising that

it already contained a mathematical compensation for the loss of

curvature, which without a proper understanding of the lines on the

map, resulted in an exaggeration of the land mass by around 4 times

its actual size.

There are several significant implications attached to the discovery

of

Antarctica

on such old maps. In particular, the use of longitude, along with

its conversion onto a two-dimensional representation implies a

knowledge of a round world, and the determination of both the poles

and equator provides the information necessary to calculate the size

of the Earth. In addiction, the first recorded sighting of 'Terra

Australis' was by Magellan in 1520, appearing on the Oronteus Finaeus

map of 1532 (above). The inscription on the 1570 map by Ortelius 'Terra

australis recenter inventa sed nondum plene cognita', suggests

that the landmass was still essentially unknown at that time,

as does the 1688 map below.

However unlikely it seems therefore, or until new evidence emerges,

we are forced to accept that

any

world map including an accurate representation of the Antarctic

coastline would have had to have been charted before the last time

it froze over, and therefore from a source as

yet unknown, and with the radio-carbon evidence from the Ross-sea core-samples

showing

that the continent has been covered by ice since around 4,000 BC, it

is closer to this period in time that we are forced to look.

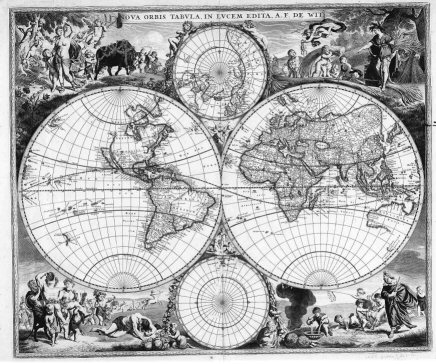

Other Maps of the Antarctic

continent.

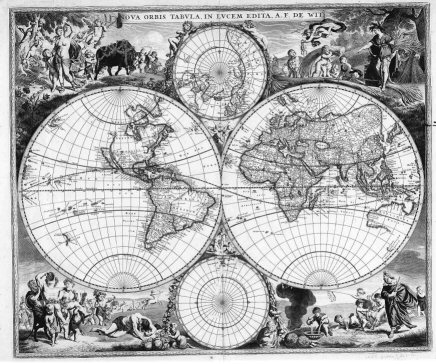

This 1688 world map illustrates the level of ignorance in Europe at

that time.

D uring his investigation, Hapgood

came to realise that several other ancient maps (such as the

Dulcert Portellano of 1339 AD), also appeared to display

evidence of longitude and latitude, and included the same

mathematical lines of projection known as the �Twelve wind

system�. His researches led him to compare ancient �portelano�

maps with several mappa-mundii which emerged in the

middle-ages, concluding that many of them were 'almost unaltered

copies of the same original'

(4).

The connection between the Piri-reis map and Constantinople led him

to speculate on the possibility that the map may have had its roots in

the store-house of knowledge, libraries etc that existed

there until the 12th century when the city was sacked by

the Christian crusaders, and following which a series of maps with

an identical geometric fingerprint, began to

appear in Europe and the Middle-east. The presence of the same

fingerprint in certain Greek maps and the information in the legend

of the Piri-reis map that it included sections composed in �the

time of Alexander�, led him to suggest that these originals

must in turn have originated from the renowned Library of Alexander

(founded in 330 BC and sacked by the Muslims in 641 AD).

As we know that the outline of the South American continent hadn�t

been completely charted by 1513AD, we are safe in assuming that

Columbos contribution of his map of the

Caribbean

islands most likely served as a confirmation to Piri-reis when he

made his map. He would also had had available to him a strong

Middle-eastern tradition of astronomy and geometry with records of

longitude from the Middle-east stating that in �1267 the Arab

astronomer Zamaruddin built the first wooden global sphere with

latitudes and

longitudes and correct ratio sea/land of 70/30�

(28).

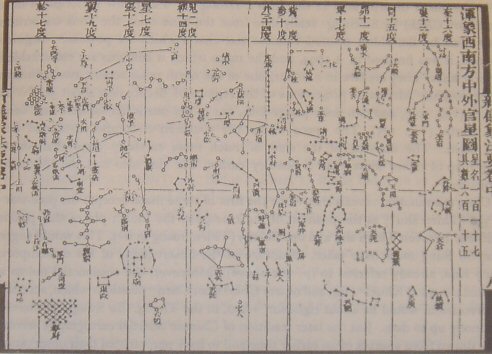

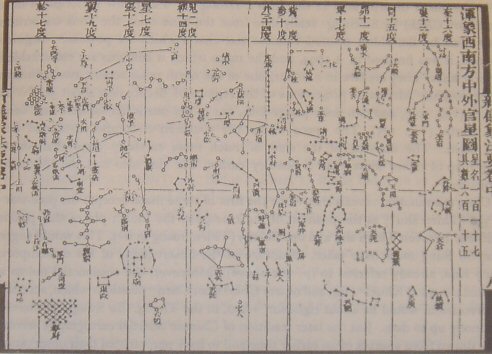

Further east, there is evidence that longitude was understood and

used by the Chinese slightly ahead of this, with the concept of

longitude shown to be understood at least as far back as 1092 AD, as

shown in the star chart published by a Chinese mechanical engineer

of the Son Dynasty called Su Song, (right), which includes

a �Mercatorial� projection of the heavens. We also have the

evidence of a carved map from 1137 AD, which shows the outline of

China at its correct longitudes and latitudes and a record from the

14th century, that �Wang Da Yuan achieved a

transoceanic passage from Mozambique to Sri Lanka using a

combination of compass and star linked positions called gouyang

Qianxing to determine latitude and longitude�

(28).

From the same source, we are offered a map of the world from a

Chinese called Zeng He, drawn in 1418 AD (with a meridian at

Nanjing), but even the earliest Chinese records appear long after

the time of �Alexander the Great�, and Hapgood�s theory of a common

source from the time of the Greeks must be taken seriously. longitudes and correct ratio sea/land of 70/30�

(28).

Further east, there is evidence that longitude was understood and

used by the Chinese slightly ahead of this, with the concept of

longitude shown to be understood at least as far back as 1092 AD, as

shown in the star chart published by a Chinese mechanical engineer

of the Son Dynasty called Su Song, (right), which includes

a �Mercatorial� projection of the heavens. We also have the

evidence of a carved map from 1137 AD, which shows the outline of

China at its correct longitudes and latitudes and a record from the

14th century, that �Wang Da Yuan achieved a

transoceanic passage from Mozambique to Sri Lanka using a

combination of compass and star linked positions called gouyang

Qianxing to determine latitude and longitude�

(28).

From the same source, we are offered a map of the world from a

Chinese called Zeng He, drawn in 1418 AD (with a meridian at

Nanjing), but even the earliest Chinese records appear long after

the time of �Alexander the Great�, and Hapgood�s theory of a common

source from the time of the Greeks must be taken seriously.

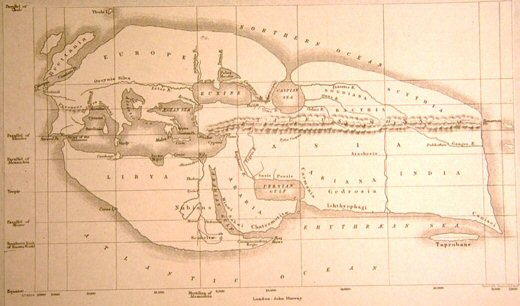

We can see that the Greeks had the technical ability to create such

a map, with records of a knowledge of a spherical earth from

Pythagoras of Samos (580-500 BC), and the first definite known use

of longitude in the great �Geographica� world atlas made by

Claudius Ptolemy in 150 AD. Although Ptolemy�s work was lost for

over a thousand years, a copy without maps surfaced around

1300 AD, and the thousands of references to place names, most of

which included coordinates, enabled re-creations of Ptolemy�s maps

to be made, with printed copies on sale in Bologna by 1477 AD,

making it likely that Admiral Reis made us of these for his world

map. Sobel (19), states that Ptolemy was known to have used both

longitude and latitude for the 27 maps of his first world atlas, and

although she mentions that 'Lines of latitude and longitude began

criss-crossing our worldview in ancient times, at least three

centuries before the birth of Christ', she offers no further

information to qualify this statement.

The legend on the Piri-reis map states that several maps from the �days

of Alexander� (356�323 BC), were used to compose the map, and

although Ptolemy lived around 200 years after Alexander, it is well

known that he, for example, relied greatly on the authority of

earlier sources for his maps

(19),

with references to

�Marinos

of Tyre�

having been cited in Geographica by Ptolemy himself, which

might explain why he broke from tradition, and placed his zero

longitude 'meridian' through the 'Fortunate Isles'

(Canary Isles), along the western edge of Africa, as only one other

person before him had; the aforesaid Marinos of Tyre, from Lebanon,

who placed his zero latitude at approximately 36� N, sending it

directly through the straits of Gibraltar and into ancient Nimrud

(36� 06� N). We can see however that other earlier eminent Greek

cartographers such as Eratosthenes (276�194 BC), who was appointed

as librarian of the Alexandrian library in 236 BC, and who is known

to have used all the material available to him to create a world map

to correct the Greek perception of the world at his time, used

Alexandria for his meridian. He also used only 60 degrees of

separation called Hexacontades, with the Babylonian division

of a circle not being officially introduced to Greece until the

second century BC by Hipparcus of Rhodes (190�120 BC).

|

Name of Cartographer |

Zero Longitude |

Zero Latitude |

|

|

|

|

|

Eratosthenes (236 BC) |

Alexandria |

Alexandria |

|

Marinos of

Tyre |

Canary Isles |

Nimrud (36� 06� N) |

|

Ptolemy (150 AD) |

Canary Isles |

Equator. |

|

Mercator |

London (0�) |

(23�

30' N) |

The fact that the centre of the map changes with each cartographer

offers us a means of being able to determine more about its origin.

As the Piri-reis map was found to centre in the region of Syene,

along the same longitude as Alexandria (founded in 332 BC), it would

suggest that the original cartographer had an affinity with this

particular longitude, as did Eratosthenes, the maker of the earliest

recorded Greek world map, who also made the first accurate

calculation the circumference of the world. It is strongly suspected

that he was assisted in these accomplishments through the

availability of earlier knowledge collected and housed in the

Library of Alexandria. We now turn to the centre of the Piri-reis

map which, as it turns out not only holds the key to its own origin,

but at the same time points to a fundamental historical moment of

human endeavor, one that has hitherto passed unrecognised.

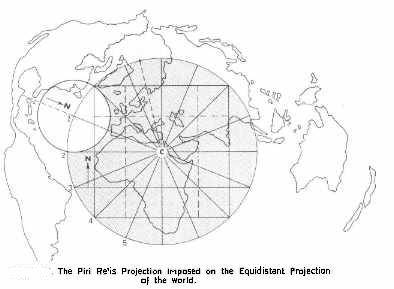

Although only the left-third of the map now remains, the remaining 'Rose

des vents' on the map enabled Hapgood to project for the

cartographic centre (see below), which was calculated to fall in 'the

region of Syene', in Egypt, and following a series of more

accurate tests he determined that the centre of the map was situated

on the ancient Tropic of Cancer, and on the same Meridian as later

Alexandria (at 30� longitude).

Centre of Piri-reis map - (24� 06� N, 30� 00� E)

This particular latitude has a significance as it was in Syene, on

Elephant island that there existed a large well which was known to

Eratosthenes to have cast no shadow on the midday summer solstice.

Even at the time of Eratoshtenes this fact was no longer true due to

the change in angle of the solstice shadow over time. In fact, at the time of

Eratosthenes (276 BC - 194 BC), the Tropic of Cancer was around 23� 43� N , and the region

of Syene, or Aswan, which is situated

at 24� 5' 23" N, would have only worked in

the way described at around 3,000 BC (See

calculation below).

|

Latitude of Aswan (Syene, Swenet) - 24 5' 23"

Tropic of cancer today (2000 AD) - 32 26' 22"

(Tropic currently decreasing by 0.47" per year -

(ref Wilkipedia)

Distance in degrees between Aswan and current

tropic = 39' or (2,340")

2,340 / 0.47 = 4978.7 yrs (approx 3,000 BC)

|

The

fact that the map centered on the region of Syene is of great

interest, as we know that Eratosthenes was aware of the significance

of this latitude in his estimates of the earth, and strongly

suggests that he was privy to Egyptian knowledge of geodesy and

astronomy.

Eratosthenes knew that on the summer solstice at

local noon in the Ancient Egyptian city of Swenet (known in Greek as

Syene) on the Tropic of Cancer , the sun would appear at the zenith,

directly overhead. He also knew, from measurement, that in his

hometown of Alexandria, the angle of elevation of the Sun would be

1/50 of a full circle (7�12') south of the zenith at the same time.

Assuming that Alexandria was due north of Syene he concluded that

the distance from Alexandria to Syene must be 1/50 of the total

circumference of the Earth.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swenet)

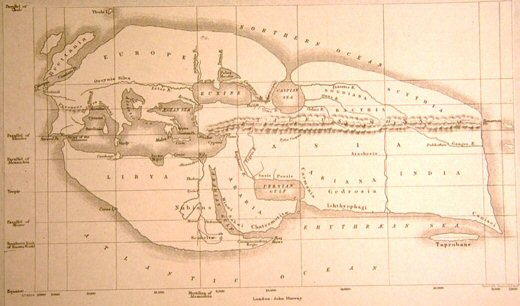

It is clear from the 19th cent. reproduction of Eratosthenes map (below) that the Piri-reis map

shows no similarity to it whatsoever. However, it is interesting to

note that while Alexandria marks the centre point on the map, it is

the latitude of Syene which is used to denote the latitude of the

tropic of cancer (note on left margin). It seems then, that he too

used a latitude with an

astronomical significance which no longer applied at his time.

There have

been several suggestions that geodetic measurements were observed in

Egypt before the Greeks, and it is possible that Eratosthenes had

some of this available to him.

Strabo the

Geographer, stated that �the science of

land-measuring originated along the Nile in Egypt', from a

necessity to record the boundaries of the nomes (provinces) of the

country, and it is suspected from the placement of sacred Egyptian

cities and shrines that a knowledge of the earth as a globe, its

dimensions and a division into 360�, existed in ancient Egypt, as

seem in the Piri-reis map but not by Eratosthenes, who

divided the globe into 60 divisions

(of 6�).

In conclusion then, what we appear to have in these ancient maps,

are copied fragments of earlier maps based on a 'sophisticated

understanding of the spherical trigonometry of map projections'

(4),

which, by their own testimony trace back at least to the time of

the Greeks, but with a suggestion that certain facts and figures may

have been passed down to them from the Egyptians and other sources.

They are clearly the result of a deliberate and successful exercise

at mapping the world, and as yet, the presence of the Antarctic continent on

any map before the 16th century has yet to be explained, as does the

high level of mathematics and geometry involved in such an

undertaking.

Ancient Cartography ۞

Egyptian Geodesy

(Prehistoric

Turkey)

|

The recognition of the Antarctic continent on certain ancient

world-maps may well turn out to be Hapgood�s most significant

discovery as, apart from the fact that there is no record of anyone

ever having charted the continent, it is a feat said by geologists

to have been last physically possible only through a window of

opportunity between 10,000 BC and 4,000 BC

The recognition of the Antarctic continent on certain ancient

world-maps may well turn out to be Hapgood�s most significant

discovery as, apart from the fact that there is no record of anyone

ever having charted the continent, it is a feat said by geologists

to have been last physically possible only through a window of

opportunity between 10,000 BC and 4,000 BC

longitudes and correct ratio sea/land of 70/30�

longitudes and correct ratio sea/land of 70/30�