|

Location:

Antequera, Spain. |

Grid Reference:

37� 1' 28.51" N,

4� 32' 47.38" W. |

Cueva de Menga Complex:

(Passage Mounds).

Cueva de Menga Complex:

(Passage Mounds).

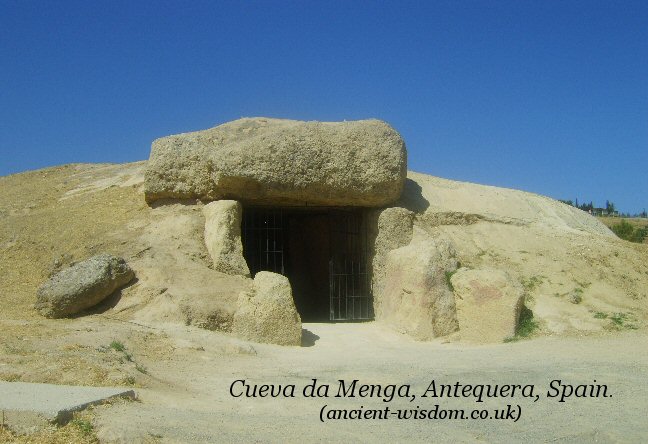

The Cueva de Menga is famous for

being one of the largest dolmens in Europe, if not the

world. Largest stones estimated at 180 Tons

(4)

The tombs have been cleared

out by tomb raiders long ago, and the few remains are now on display in

the Museo Arqueol�gico (Archaeological Museum) in M�laga. The museum

is located in the Alcazaba, the maurean residence.

The oldest is said to have been built around 3,700

BC.

(5)

The stone used comes from de la Cruz, about 1

mile from the site.

(2)

The monuments are unusual in that they were partially cut into

hillsides and each is constructed differently.

(Map of Location)

These three Dolmen/passage mounds are often ignored in

prehistoric European literature, however, their importance is obvious

from the sheer size and scale of the stones used for the monuments, with

the largest regularly estimated at around 180 Tons

(4)

Recent research has shown that Menga's anomalous

orientation can be explained by an area of specieal significance on the

north face of La Pena, at the place known as Matacabras Cave, which has

'schematic-style' prehistoric paintings in it. (Ref: Site pamphlet)

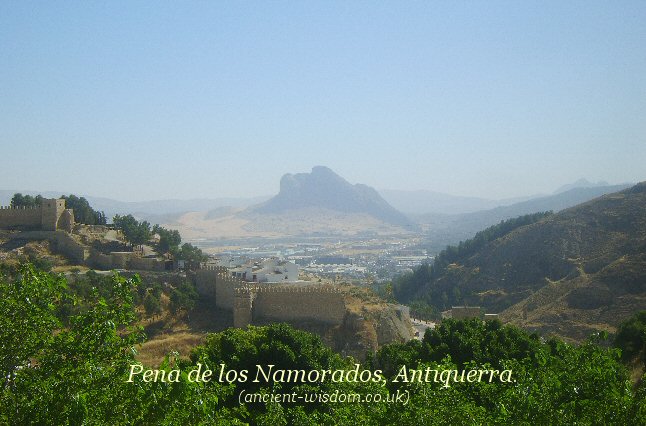

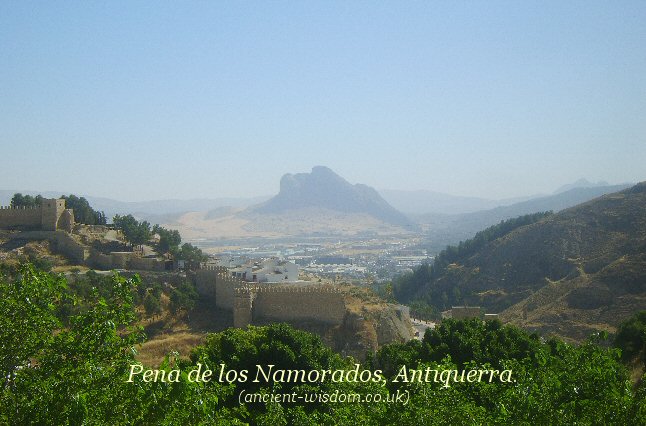

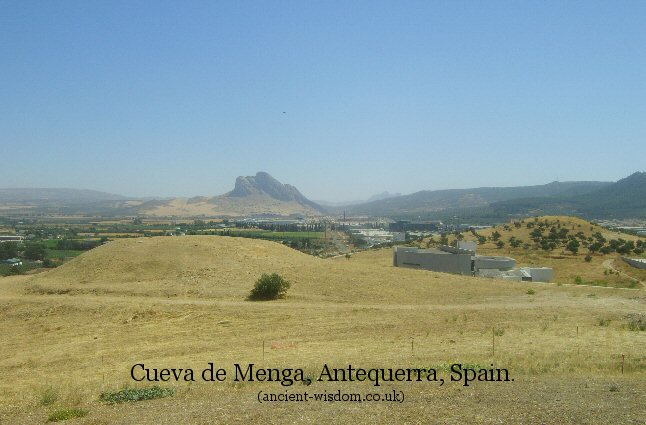

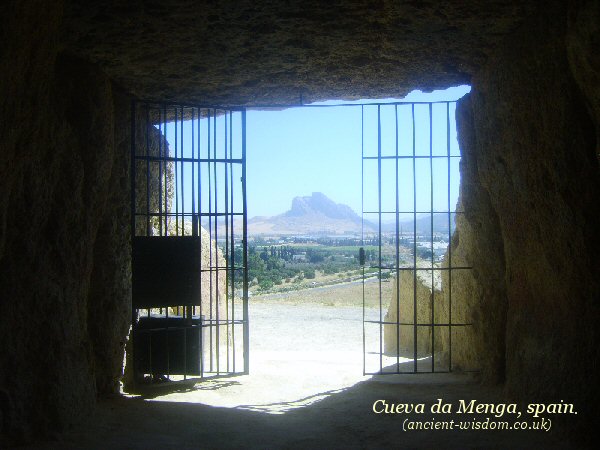

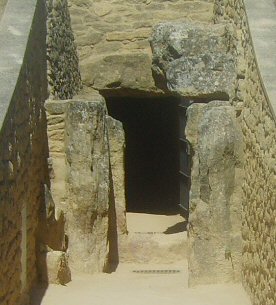

The view of the Cueva de Menga front left, the location of

the Neolithic settlement centre right, and the ever-present Pena

de los Namorados in the distance (As seen from the top of Cueva

de Viera).

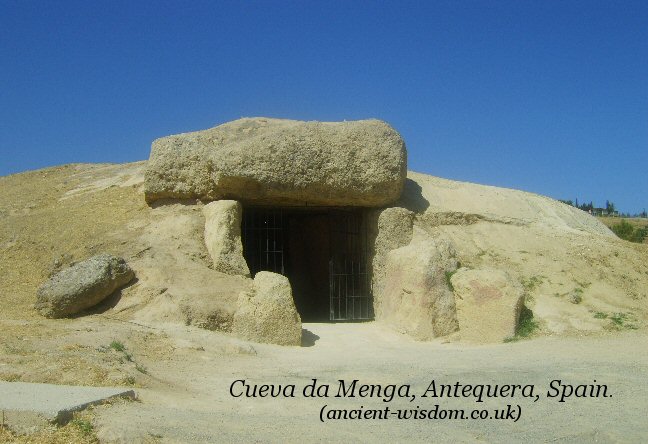

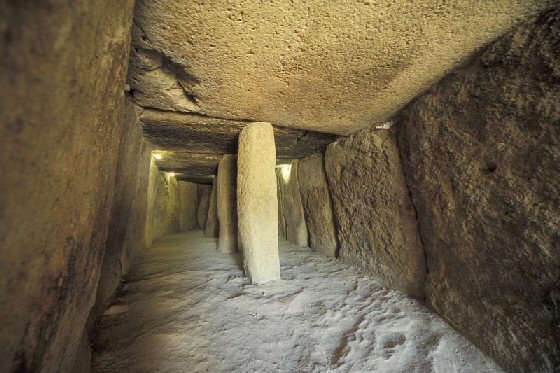

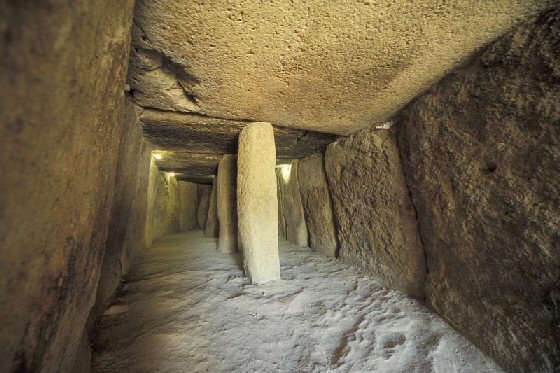

Built on a natural mound, the main chamber is composed of five

capstones supported by three squared pillars, cut into the stones

that compose the floor. Anthropomorphic scenes are recorded on its

walls. When the grave was opened and examined in the 19th century,

archaeologists found the skeletons of several hundred people inside

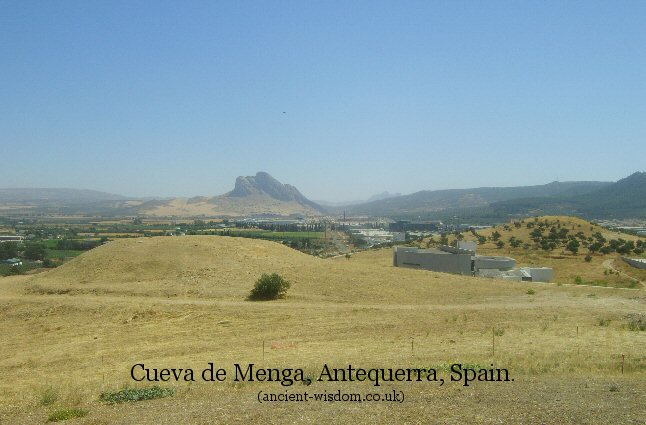

From below, the passage mound appears to be a part of the natural

mound..

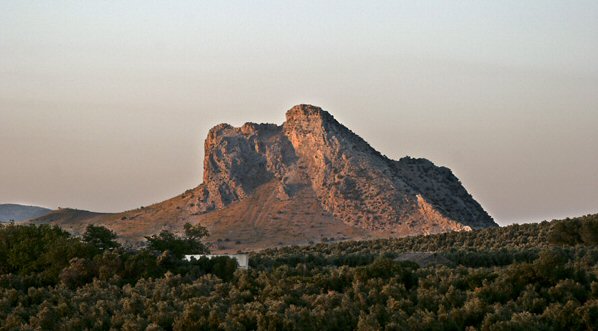

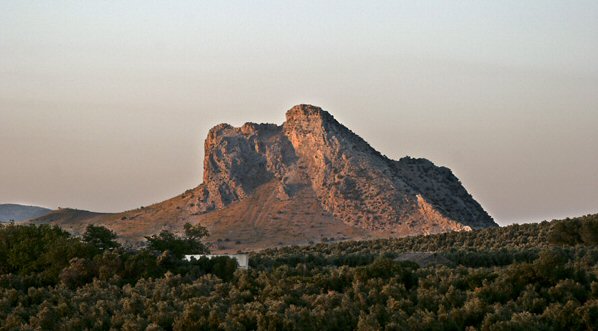

The ever present 'head' lies directly in

front of the Passage mound, and is also aligned with both Cueva

de Menga and Cueva de Viera.

The 'anomalous' orientation of the passage

mound, facing northeast (azimuth 45�), to the north of the

summer solstice sunrise. In the context of the monument (and

other contemporary monuments), appears to be explained by its

alignment with the ever-present La Pena.

This text from 1854 is one of the earliest

descriptions of the Cueva de Mengan site.

'About a quarter of a mile to the eastward of the

town (Antequera), on the road to Archidona, are three conical hills,

from sixty to eighty feet in height, remarkable for the regularity of

their outline, and covered with olive trees. On ascending the one

nearest the town, and close to its summit, you find yourself opposite

the cave. It presents a perfect porch, symmetrical in shape, but

composed of rough stones of gigantic magnitude... ...In length, the cave

measures seventy-one feet, and lies due east and west; the entrance

faces eastward and looks towards the other two similar hills; and beyond

them gain, at almost the distance of a league, rises abruptly from the

plain the Pena de los Enamorados, which from here, presents its most

picturesque appearance.'

(1)

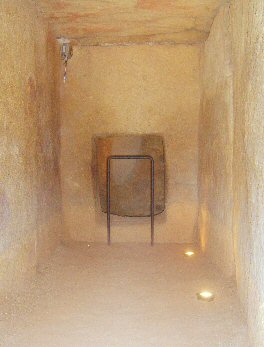

'Signor Mitjana [in 1841], in

searching for bones, weapons, or other remains, and perhaps, for other

chambers deeper in the hill, caused a shaft to be sunk in the interior,

between the third pillar and the extremity, but discovered nothing; and to

give light to his workmen, broke out at the end a large hole, four or five

feet square, which considerably impairs the effect and uniformity of the

place'.

(1)

Three pillars support the huge

limestone conglomerate capstones, some of which are already noticeably

cracked and broken.

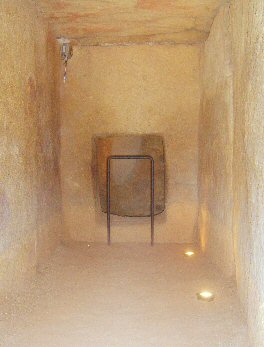

The well-shaft inside the chamber

(left), and 'anthropomorphic' engravings (right).

The well-shaft , which is 1.5m

diameter and 19.5m deep, has water at the bottom. it was uncovered through

recent archaeology.

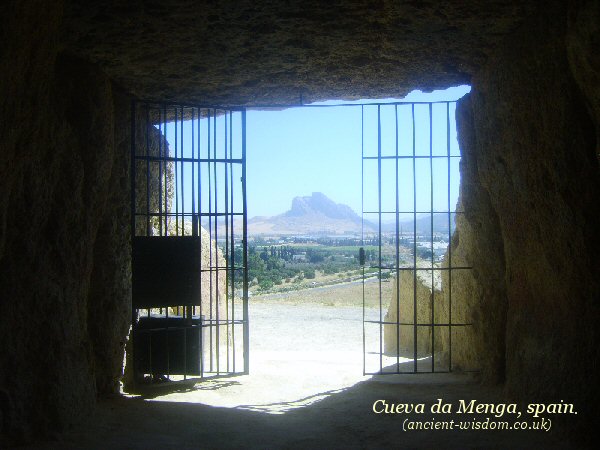

The entrance to the monument faces

the 'Pena de los Namorados' (Lovers Peak). It is reasonably clear

that this peak was a primary consideration in the selection of location for

the Cueva de Menga complex and this example of deliberate placement confirms

the idea that the landscape itself was an important aspect of the Neolithic

mind, as was the association between megaliths and 'simulacrum', a

suggestion which infers that the rocks and earth were seen as living

entities, which would have endowed the site with a special quality.

(More about

Simulacrum)

Article: (Antequera

burial dolmen is 1,000 years older than previously thought)

Carbon dating carried out on material at the entrance

of the Menga dolmen in Antequera, M�laga in June 2006 has made the

burial monument 1,000 years older than previously thought.

The latest analysis dates the site at 3790 B.C. in Neolithic times and

not dating from the Copper age as previously thought.

Now Granada University professor, Francisco Carri�n, has confirmed

second analysis carried out by Swiss investigators which confirms the

date with two samples at 3790 and 3730 B.C.

It places the Menga dolmen as unique among the 300 or so which are to be

found in the Antequera region, and not only as it is the only one which

does not face East but instead to the summer solstice in the North East.

|

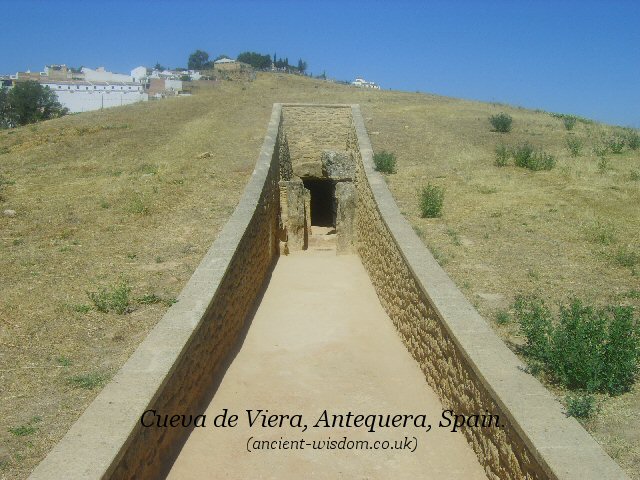

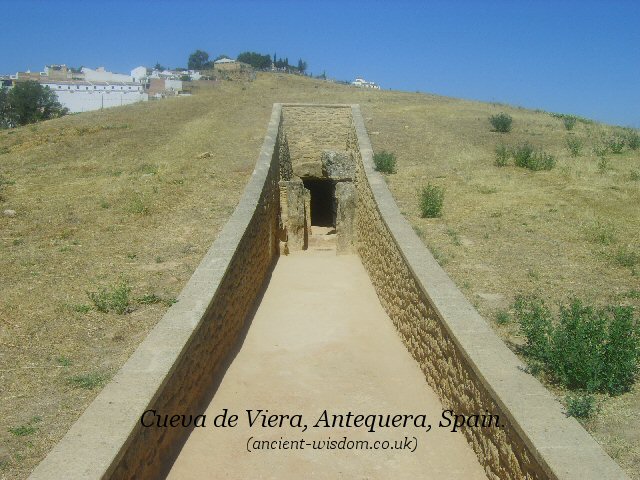

The Cueva monument is a passage mound

consisting of a 22m long passage divided into two sections, at the end

of which there is a small square chamber entered through a holed

'portal' stone. The stone interior is covered by a mound 55m in diameter

and orientated along a 96� azimuth (a common theme in Iberian

megaliths).

'On the same hill about 80 yards from the Cueva de

Menga, almost identical in general plan but differing considerably in

detailed construction and design. Consisting of a single chamber entered by a

long gallery divided from it by a stone doorway at one end and by a similar

portal from an outer passage of rough stones at the other end. Beyond the outer

doorway in the form of a rectangular opening in a stone slab is the remains of a

portal, and cup-markings on three of the uprights of the passage and outside the

door'.

(2)

'The Cuevas de Viera has a long orthostat-lined

passage with porthole slabs and a small square chamber. A cemetery of

rock-cut tombs of the Bronze-age imitating the tholos form is nearby''.

(3)

As it was before restoration...

And as it is now...

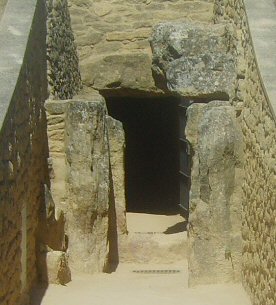

The original structure had at least two 'Holed

stones' in it, one now broken.

In the case of Cueva de

Viera, one holed stone was placed at the entrance of the small inner

chamber, and another part-way along the corridor. Their purpose is

speculative, but one has to pass through them to enter.

(More about Holed Stones)

The Passage was

orientated towards the sun at the autumn equinox.

|

Cueva de Romeral:

'Tholos' / Passage mound. Cueva de Romeral:

'Tholos' / Passage mound.

'Two kilometres away in an isolated and neglected double-chambered

tomb of cupola type, the Cueva de Romeral, the inner doorway from the

main chamber is formed by four pillars and a lintel, with the tops

of the inner pair of door jambs sloped downwards towards the

chamber'.

(2)

'The Cueva de Romeral has a magnificent corbel vault nearly 5-metres

high, dry-stone 'Tholos', and a passage over 30 metres long'.

(3)

The tumulus is orientated on an azimuth of 199 , south south-west,

towards the highest elevation on the El Torcal mountains, known as

Camorro de las Siete mesas.

|

|

Other Spanish Dolmens:

'Dolmen'

de Soto - Andalucia. (Passage mound/Dolmen)

Contains engravings on several of

the orthostats.

It was discovered by Don Armando de

Soto in 1922. Is the more important prehistoric monument of the province

of Huelva.

(More about Soto soon) |

Gallery of Images:

(Other Prehistoric

Spanish Sites)

|

Cueva de Romeral:

'Tholos' / Passage mound.

Cueva de Romeral:

'Tholos' / Passage mound.