|

Location:

Near

Taronik,

Armenia

(Since 1991) |

Grid Reference:

40� 8' 34" N, 44� 6' 59" E |

Metsamor:

(Prehistoric Citadel).

Metsamor:

(Prehistoric Citadel).

The site is located in Armenia, and Not Turkey.

(Independent since 1991)

Metsamor is a working excavation and museum on the site of an

ancient city

complex with a large metallurgical and astronomical centre (occupied ca.

7,000 BC - 17th c. CE). The site occupies a volcanic hill and surrounding

area.

The citadel on top of the

volcanic hill is about 10.5 hectares in size, but the entire city is

believed to have covered 200 hectares at its greatest extent, housing up to

50,000 people. Excavations have shown

strata of occupancy going back to the Neolithic period (7,000-5,000 BC), but

the most outstanding features of the site were constructed during the early,

middle and late Bronze Ages (5,000-2,000 BC). Inscriptions found within the

excavation go back as far as the Neolithic period, and a sophisticated

pictograph form of writing was developed as early as 2000-1800 BC. The

�Metsamor Inscriptions� have a likeness to later scripts.

(Map of

site - How to get there)

|

Metsamor: 'Medzamor' -

('Black swamp' or 'Black quicksand') |

Excavations began at Metsamor in 1965 and are still in

progress, led by Professor Emma Khanzatian. The most recent excavation work

occurred in the summer of 1996, along the inner cyclopic wall. Excavations

have shown strata of occupancy going back to the Neolithic period

(7,000-5,000 BC), but the most outstanding features of the site were

constructed during the early, middle and late Bronze Ages (5000-2,000 BC).

Inscriptions found within the excavation go back as far as the Neolithic

period , and a sophisticated pictograph form of writing was developed as

early as 2000-1800 BC. (1)

Metallurgy

-

The excavation has uncovered a large metal industry, including a foundry

with 2 kinds of blast furnaces (brick and in-ground). Metal processing at

Metsamor was among the most sophisticated of its kind at that time: the

foundry extracted and processed high-grade gold, copper, several types of

bronze, manganese, zinc, strychnine, mercury and iron. Metsamor�s processed

metal was coveted by all nearby cultures, and found its way to Egypt,

Central Asia and China. The iron smelting process was not advanced in

Metsamor, probably due to the vast quantities of pure bronze alloys at hand,

and Metsamor primarily mined and sold iron ore to neighbouring cultures

which took better advantage of its properties.

The Foundry

- The foundry dates from the Early Bronze Age (ca. 4,000 BC) though recent

digs in the area uncovered signs of metal processing as early as 5,000 BC.

The complex of smelting furnaces and moulds date from the mid

Bronze to Early Iron Age (3,000-2,000 BC). The complex becomes more

astounding the more you walk through it. Several huge underground caves

were uncovered that are thought to have been storehouses for base metal, as

well as a granaries for winter months. Stretching just below and around the

Upper Citadel, the foundries processed Copper, Bronze, Iron, Mercury,

Manganese, Strychnine, Zinc and gold. The first iron in the ancient world

was probably forged here, though it was not considered as important as

bronze, giving the jump on development to the Babylonians. The Foundry

- The foundry dates from the Early Bronze Age (ca. 4,000 BC) though recent

digs in the area uncovered signs of metal processing as early as 5,000 BC.

The complex of smelting furnaces and moulds date from the mid

Bronze to Early Iron Age (3,000-2,000 BC). The complex becomes more

astounding the more you walk through it. Several huge underground caves

were uncovered that are thought to have been storehouses for base metal, as

well as a granaries for winter months. Stretching just below and around the

Upper Citadel, the foundries processed Copper, Bronze, Iron, Mercury,

Manganese, Strychnine, Zinc and gold. The first iron in the ancient world

was probably forged here, though it was not considered as important as

bronze, giving the jump on development to the Babylonians.

(Metallurgy in Prehistory)

Funerary remains

- The discovery of thousands of people buried in simple graves and

large burial mounds revealed a history of Metsamor�s burial rituals and a concern for hiding wealthy tombs. Like the

Pharaohs buried in the Valley of the Kings, Metsamor�s rulers tried to

thwart grave robbers by hiding the locations of royal tombs. Fortunately

the grave robbers at Metsamor were not as lucky as those in Egypt, and the

Mausoleums revealed intact and richly adorned burial vaults, giving us an

excellent glimpse into the traditions for preparing the body for the

afterlife.

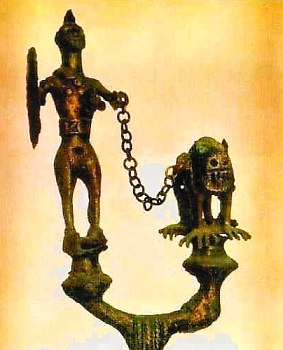

Among the artefacts uncovered in the royal tombs were evidences of great

wealth; Gold, silver and bronze jewellery and adornments were found over and

next to the body, which was placed in a sitting foetal position in a large

stone sarcophagus (early Metsamor) or lying in a casket (late Metsamor).

The bodies were laid out with their feet oriented towards the East, so they

could greet the sun and follow it to the afterlife in the West. Included in

the vaults were the skeletal remains of horses, cattle, domesticated dogs

and humans, presumed to be servants or slaves to the deceased. The

sacrifice of slaves and animals was a common feature of burial rituals

during the Bronze and Early Iron Age, as they were considered necessary to

assist their master in the next life. In addition to jewellery, pottery and

tools, excavators discovered pots filled with grape and pear piths, grains,

wine and oil. The fruit piths are a prominent part of the food offerings,

and considered a necessary part of the funeral rites. Among the artefacts uncovered in the royal tombs were evidences of great

wealth; Gold, silver and bronze jewellery and adornments were found over and

next to the body, which was placed in a sitting foetal position in a large

stone sarcophagus (early Metsamor) or lying in a casket (late Metsamor).

The bodies were laid out with their feet oriented towards the East, so they

could greet the sun and follow it to the afterlife in the West. Included in

the vaults were the skeletal remains of horses, cattle, domesticated dogs

and humans, presumed to be servants or slaves to the deceased. The

sacrifice of slaves and animals was a common feature of burial rituals

during the Bronze and Early Iron Age, as they were considered necessary to

assist their master in the next life. In addition to jewellery, pottery and

tools, excavators discovered pots filled with grape and pear piths, grains,

wine and oil. The fruit piths are a prominent part of the food offerings,

and considered a necessary part of the funeral rites.

Other funeral objects

discovered were rare amethyst bowls, ornamented wooden caskets with inlaid

covers, glazed ceramic perfume bottles, and ornaments of gold, silver and

semiprecious stones, and paste decorated with traditional mythological

scenes typical of local art traditions. Egyptian, Central Asian and

Babylonian objects were also found at the site, indicating that from

earliest of times Metsamor was on the crossroads of travel routes spanning

the Ararat plain and linking Asia Minor with the North Caucasus and Central

Asia. By the early Iron Age Metsamor was one of the �royal� towns, an

administrative-political and cultural centre in the Ararat Valley.

The cyclopean walls

- The walls date from the 2nd millennium BC, when the site was fortified during the

Urartian

Era. The stone blocks average 20 tons in weight, and are more than 3 meters

thick in places.

During the Middle Bronze

Period (late 3rd to mid 2nd millennium BC) there was a surge of urban growth

and a development of complex architectural forms which extended the

boundaries of the settlement to the area below the hill. Basically, that

area within the inner cyclopean walls are the older city, and that beyond

represent newer areas. By the 11th c. BC the central city occupied the

lowlands stretching to Lake Akna, and covered 100 hectares (247 acres).

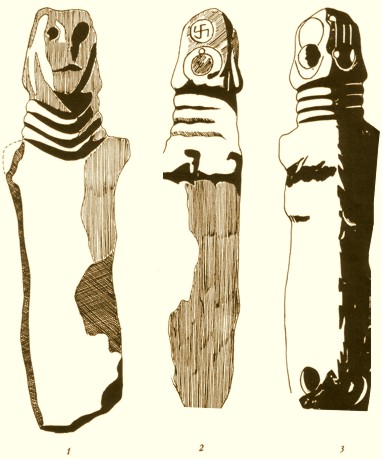

Inscriptions

- En route to the temple site,

just below the old citadel, is an incline on the stone hill. Carved into

the hill is an intricate and large (almost 20 meters long) design. The

design resembles a rudimentary map, and the shape of the rock resembles the

Ararat side of Mt. Aragats in miniature. Inscriptions also include several

early Haikassian script symbols (though carved at Metsamor much earlier, ca.

3,000 BC), and forms one of the basis' for establishing the old Armenian

script during the Bronze Age around Metsamor. Inscriptions

- En route to the temple site,

just below the old citadel, is an incline on the stone hill. Carved into

the hill is an intricate and large (almost 20 meters long) design. The

design resembles a rudimentary map, and the shape of the rock resembles the

Ararat side of Mt. Aragats in miniature. Inscriptions also include several

early Haikassian script symbols (though carved at Metsamor much earlier, ca.

3,000 BC), and forms one of the basis' for establishing the old Armenian

script during the Bronze Age around Metsamor.

Three

temples were uncovered and are now covered by a metal structure, Vandals have

desecrated most of the altars you see. Luckily they are only three of an

entire complex that was preserved by recovering them after the initial dig

in 1967. The temples are unlike any other uncovered in Western Asia and

the Ancient world, indicating a very distinct culture at Metsamor during the

2nd-1st millennia.

Within the altar spaces are

numerous bowls set into the temple floor and a complex series of clay

holders. Very little is understood about the ritual that occurred here,

though animal sacrifice was a part. The holders probably held rare oil

mixed with myrrh and frankincense, purified wine, wheat and fruit (seeds

were discovered in some of the shallow bowls).

Astronomy - Astrology at Metsamor:

The astronomical observatory

predates all other known observatories in the ancient world. That is,

observatories that geometrically divided the heavens into constellations and

assigned them fixed positions and symbolic design. Until the discovery of

Metsamor it had been widely accepted that the Babylonians were the first

astronomers. The observatory at Metsamor predates the Babylonian kingdom

by 2000 years, and contains the first recorded example of dividing the year

into 12 sections. Using an early form of geometry, the inhabitants of Metsamor were able to create both a calendar and envision the curve of the

earth.

(1)

It should be no

surprise to anyone who knows something of Armenia's history that

astronomy is such an important part of the national character.

Sun symbols, signs of the zodiac, and ancient calendars

predominated in the region while the rest of the world was just

coming alive, culturally speaking. Egypt and China were still

untamed wilderness areas when the first cosmic symbols began

appearing on the side of the Geghama Mountain Range around 7000

BC. At Metsamor (ca 5000 BC), one of the oldest observatories in

the world can be found. It sits on the southern edge of the

excavated city, a promontory of red volcanic rocks that juts out

like the mast of a great ship into the heavens. Between 2800 and

2500 BCE at least three observatory platforms were carved from

the rocks. The Metsamor observatory is an open book of ancient

astronomy and sacred geometry. For the average visitor the

carvings are indecipherable messages. With Elma Parsamian, the

first to unlock the secrets of the Metsamor observatory as a

guide, the world of the first astronomers comes alive.

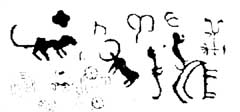

The discovery of the astronomical 'observatory'

at Metsamor and the presence of engravings which have been

speculatively called 'zodiac creatures' has given credence to the

assertion that the ancient figures of the constellations were

probably created by ancient peoples living in the Euphrates valley

and near Mount Ararat in eastern Anatolia and Armenia: Rick Ney, the

author of Karahundj, The Armenian Stonehenge, says of it:

"Parsamian's

discovery at Metsamor, and the stones at Sissian give concrete

credence to Maunder's and Olkott's theories, especially when

coupled with ca. 4,000�3,000 BC stone carvings of zodiac figures

on rocks on the Geghama Mountain Range in Armenia.".

"The Metsamorians were a trade culture," Parsamian explains.

"For trade, you have to have astronomy, to know how to

navigate." The numerous inscriptions found at Metsamor puzzled

excavators, as indecipherable as they were elaborate. Hundreds

of small circular bowls were carved on the rock surfaces,

connected by thin troughs or indented lines. But one stood out.

It is an odd shaped design that was a mystery to the excavators

of the site, until Professor Parsamian discovered it was a key

component to the large observatory complex. By taking a modern

compass and placing it on the

carving, Parsamian found that it pointed due North, South and

East. It was one of the first compasses used in Ancient times. "The Metsamorians were a trade culture," Parsamian explains.

"For trade, you have to have astronomy, to know how to

navigate." The numerous inscriptions found at Metsamor puzzled

excavators, as indecipherable as they were elaborate. Hundreds

of small circular bowls were carved on the rock surfaces,

connected by thin troughs or indented lines. But one stood out.

It is an odd shaped design that was a mystery to the excavators

of the site, until Professor Parsamian discovered it was a key

component to the large observatory complex. By taking a modern

compass and placing it on the

carving, Parsamian found that it pointed due North, South and

East. It was one of the first compasses used in Ancient times.

Another carving on the platforms shows four stars inside a

trapezium. The imaginary end point of a line dissecting the

trapezium matches the location of star which gave rise to

Egyptian, Babylonian and ancient Armenian religious worship.

The

Observatory

-

The observatory rivals the discoveries at the citadel for importance,

substantiating theories on the birthplace of the zodiac and origins of

astronomy in the ancient world. Dated ca. 2,800-2,500 BC, when the zodiac is

figured to have been concluded, the observatory was also the primary

religious site and navigation centre for the Metsamorian culture. Hundreds

of shallow bowls are carved onto the surfaces of three large rocks that rise

above the surrounding river delta. The use of the bowls are unknown, many

are linked by equally shallow "canals" (we're talking real small here, no

more than a few inches in diameter for the bowls). They might have been

filled with oil that was lit at night as part of a ritual celebration (if

so, they would look very much like a 'bowl of the universe' on earth), or

they may have been used to smelt and forge metal in another sort of ritual.

Imagination allows you to decide for yourself. The

Observatory

-

The observatory rivals the discoveries at the citadel for importance,

substantiating theories on the birthplace of the zodiac and origins of

astronomy in the ancient world. Dated ca. 2,800-2,500 BC, when the zodiac is

figured to have been concluded, the observatory was also the primary

religious site and navigation centre for the Metsamorian culture. Hundreds

of shallow bowls are carved onto the surfaces of three large rocks that rise

above the surrounding river delta. The use of the bowls are unknown, many

are linked by equally shallow "canals" (we're talking real small here, no

more than a few inches in diameter for the bowls). They might have been

filled with oil that was lit at night as part of a ritual celebration (if

so, they would look very much like a 'bowl of the universe' on earth), or

they may have been used to smelt and forge metal in another sort of ritual.

Imagination allows you to decide for yourself.

The author,

accompanied by P.Herouni, his collaborators and two students from

Moscow, spent the whole of 24 June, 2001, that is, two days after

the summer solstice, on the spot from about 5 AM until midnight, and

was able to observe and record with his personal video camera the

rising of the Sun and the Moon. He witnessed that three or four of

the holes are directed towards the point of sunrise while an equal

number of other holes are oriented towards the point of sunset on

the day of the summer solstice. The same is true of the points of

the moon rising and setting on the day when the observations took

place.

(2)

(More

about the Origin of the Zodiac)

Worship of Sirius

"Sirius is most probably the star

worshipped by the ancient inhabitants of Metsamor," Parsamian

explains. "Between 2800-2600 BCE Sirius could have been observed

from Metsamor in the rising rays of the sun. It is possible

that, like the ancient Egyptians, the inhabitants of Metsamor

related the first appearance of Sirius with the opening of the

year."

Those wanting to plot the same event from Metsamor will have to

wait a while. Sirius now appears in the winter sky, while the

inhabitants of Metsamor observed it in the summer. (Because of

the earth's rotation within the rotation of the Milky Way

galaxy, stars change their positions over time. In another 4000

years or so Sirius will again appear as it is plotted on the

Metsamor stellar map).

The Metsamorians also left behind a calendar divided into twelve

months, and made allowances for the leap year. Like the Egyptian

calendar which had 365 days, every four years the Metsamorians

had to shift Sirius' rising from one day of the month to the

next.

"There is so much I found in 1966," Parsamian adds, "and so much

we do not know. We believe they worshipped the star Sirius, but

how? I like to imagine there was a procession of people holding

lights. These carved holes throughout the complex may have been

filled with oil and lit. Just imagine what it must have looked

like with all those little fires going all over the steps of the

observatory. Like a little constellation down on earth."

Parsamian has a special regard for Metsamor, since it was she

who uncovered many of the mysteries of the inscriptions on the

observatory, answers which explained other finds uncovered at

the excavation site. "When you walk over this ancient place, you

can use your imagination to complete the picture. I love to

visit Metsamor since I feel I am returning to the ancients."

(More about Orion Worship in

Prehistory)

The Oracle at Metsamor:

Livvio Stecchini noted the curious fact that

Thebes in Egypt

is geometrically aligned with Mt. Ararat, and the oracle centre called

Dodona in

Greece, both of which are recorded as resting places for the Ark, following

the 'great flood'. He showed that the three sites are equidistant from each

other, forming an equilateral triangle. This idea was later followed

up by Robert Temple, who suggested that the nearby Metsamor was a more

appropriate location as it is more accurately positioned than Ararat. The

discoveries of advanced astronomy and geometry at this site, support the

conclusion that Metsamor was once an important oracle centre.

(More

about Oracle centres)

(Prehistoric Turkish sites)

(Archaeoastronomy) |