|

Location:

Near Heraklion, Crete, Greece. |

Grid Reference:

35� 17' N,

25� 10' E. |

Knossos:

(Minoan Capital City).

Knossos:

(Minoan Capital City).

Knossos was inhabited for several thousand years, beginning with a

Neolithic settlement sometime in the seventh millennium BC. The Palace

was first built around the original site and was

abandoned after its destruction around 1,375 BC which marked the end of

Minoan civilization.

The restorations performed by Evans have been criticized as

inaccurate, and there is a feeling that many of the details were

reconstituted (to use Evans' term) utilizing at best "educated guesses".

(Click

here for Ground-plan of Knossos)

Article: LiveScience.com (May, 2013)

'Mysterious

Minoans Were Europeans According to DNA'

'The

Minoans, the builders of Europe's first advanced civilization,

really were European, new research suggests. The conclusion,

published today (May 14) in the journal Nature Communications,

was drawn by comparing DNA from 4,000-year-old Minoan skeletons

with genetic material from people living throughout Europe and

Africa in the past and today.

"We now know

that the founders of the first advanced European civilization

were European," said study co-author George Stamatoyannopoulos,

a human geneticist at the University of Washington. "They were

very similar to Neolithic Europeans and very similar to present

day-Cretans," residents of the Mediterranean island of Crete'.

(Link

to Full Article)

|

Knossos: Capital of the Minaon Empire. |

Knossos has been inhabited longer

than any other site in Crete. The first Neolithic settlers probably

arrived some time before 7,000 - 6,000 BCE, making their the first

settlement on what was to be the eventual site of the palace. These

settlers did not make pottery but grew crops and kept animals.

The

first Minoan palace (1,900 B.C.), was built on the

ruins of a Neolithic settlement.

This was destroyed in 1,700 B.C. and a new palace built in its place.

Between 1,700-1,450 BC, the Minoan civilisation was at its peak and

Knossos was the most important city-state. During these years the city

was destroyed twice by earthquakes (1,600 BC, 1,450 BC) and rebuilt.

The city of Knossos is estimated to have held up to 100,000 people at

its peak and it continued to be an

important city-state until the early Byzantine period.

Homer states in

Odyssey,

��the great city, where Minos was king�and conversed with great Zeus.�

This remained uncorroborated until

1899 by Arthur Evans, who started digging in 1900 and uncovered the

palace of Knossos and through it, the Minoan civilisation.

The

Palace at Knossos has the same architectural design found at other Minoan palaces.

There is a central courtyard, with living rooms and storage rooms off

the courtyard. The palaces were the economic, social, religious and

political centres for the Minoan civilization.

Knossos and the Minoan empire show a sudden decline

at the same period as the Santorini (Thera) eruption which had a

devastating effect on all Mediterranean cultures the time.

Plumbing and Drainage at Knossos:

The palace had

hypocaust

heating and plumbing which brought in hot and cold

water and flushing toilets.

At Knossos,

the Minoans took advantage of the steep grade of the land to devise a

drainage system with lavatories, sinks and manholes. Archaeologists have

found pipe laid in depths from just below the surface in one area to

almost 11 feet deep in others.

They constructed a

main sewer of masonry, which linked four large stone shafts emanating

from the upper stories of the palace. Evidently the shafts acted as

ventilators and chutes for household refuse. The shafts and conduit were

formed by cement-lined limestone flags, but earthenware or burnt clay

pipes were used in the remainder of the system. These were laid out

under passages, not under the living rooms.

The sewer system

consisted of terra cotta pipes, from 4"-6" in diameter.

The rain water from

the roofs and the courts, and the overflows from the cisterns carried

the water down into buried drains of pottery pipe. The pipes had perfect

socket joints, so tapered that the narrow end of one pipe fixed tightly

into the broad end of the next one. The tapering sections allowed a

jetting action to prevent accumulation of sediment.

At Knossos we find

the earliest known flushing toilet. The toilet was screened off by

partitions and was flushed by rain water or by water held in cisterns

from conduits built into the wall.

Not just palaces

but ordinary homes were heated with sophisticated hypocaust systems,

where heat was conducted under the floor, the earliest known to exist.

In the room dubbed

the "queen's bathroom" decorated with wall frescoes, we find plaster

stands which held ewers and washing basins, and a five-foot long tapered

bathtub made of painted terra cotta and decorated with watery reeds.

There was no

obvious outlet but used water was removed and discarded into a hole in

the floor which connected to the main drain which discarged into the

river Kairatos. Some of the stone slabs of the floor at Knossos have

been partially removed to reveal the extensive sewage canal system

underneath the whole settlement.

Pipes with running

water and toilets found on Santorini are the oldest ever discovered. The

dual pipe system suggests hot and cold running water.

The 'Horns of Consecration'

(left) have been compared with the 'Altar of Sin' (right), in the

'Temple of the Moon' on Bahrain (Dilmun).

(Click here for more)

|

The Minoan Snake Goddesses:

Several snake goddesses were found

buried in cists in the ground, named by Evans the 'Temple Repositories'.

One of the statuettes had been deliberately broken before being placed

in the repository and it has been suggested that this might have been a

way of "killing" the cult figurines. Two of the Snake Goddesses have

been restored and are among the must-see treasures in the Museum at Heraklion.

The Snake Goddess:

Faience figurine found at the temple repository at Knossos.

The neck

and head of the figurine above is a reconstruction, presumably based upon the

head of the other snake goddess and from the numerous examples of women's heads and faces

painted in Minoan frescoes. The headpiece is also a reconstruction,

based largely on a fragment of the front part which included a series of

three dark-painted, raised medallions. The left forearm with the snake

being held in the left hand is also a reconstruction. Only the tail of

the snake, which protrudes above her fist, is original; the portion

below the wrist, with the head, is a reconstruction.

The similar wooden statuette of woman with movable

arms was found in 1896 by James Edward Quibell in a cache of magical

objects in a tomb dating to Dynasty XIII (1786-1633 BCE) discovered

under the Ramesseum, the mortuary temple of Ramesses II (1290-1224 BCE),

at Thebes. The statuette, which holds a

metal snake-wand in each hand, is thought to represent a female sau,

a type of magician, who could supply magical protection (the Egyptian

verb sa means "to protect") both by making charms and amulets,

and by using spoken and written charms.

Besides the statuette, the cache also included some

magico-medical papyri and a twisting bronze snake wand (now in the

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) which was evidently intended to be held

in the middle where its body flattens out. It is approximately twice the

size of those held by the wooden figurine.

An interesting feature of the Egyptian statuette is

its moveable arms which could be raised so that the metal snakes in each

hand are held up in a manner reminiscent of the Minoan Snake Goddess.

Large

portions of the other snake-goddess figurine seen above are also reconstructions. Of the original

figurine, only her torso, right arm, head, and her hat (except for a

portion at the top) were found. It not at all clear, for example, that

it is one single snake that has its head in her right hand and its tail

in her left.

|

Minoan script-'Linear-A'

'The written

language of the Minoans is called

Linear A by archaeologists, linguists and historians, and has not yet

been deciphered. The

Mycenaean language,

Linear B,

was not deciphered until the 1950s, and linguists hope one day to crack

the code, as more writings are unearthed in excavations. One example is

the

Phaistos Disc, where the writing runs in a spiral from the

outside to the centre. Linguists now believe that Linear A and Linear B

are very similar. Until recently it was believed that Linear A was not

related to Linear B, an ancestor of the Greek language, and was not an

Indo European language, a family that includes ancient Greek and Latin.

However, this view has changed. Linguists have discovered a close

relationship between Linear A and Sanskrit, the ancient language of

India, with connections to Hittite and Armenian, making it clear that

Linear A is an Indo European language'.

(3)

An

example of 'Linear-A'.

(A comparison of Linear-A and B and Other Proto-Greek scripts).

The Phaistos Disc is a disk of fired clay from the

Minoan palace of Phaistos, possibly dating to the middle or late Minoan

Bronze Age (2nd Millennium BC). It is about 15 cm (5.9 in) in diameter

and covered on both sides with a spiral of stamped symbols. Its purpose

and meaning, and even its original geographical place of manufacture,

remain disputed, making it one of the most famous mysteries of

archaeology. This unique object is now on display at the archaeological

museum of Heraklion in Crete, Greece.

The disc was discovered in 1908 by the Italian

archaeologist Luigi Pernier in the Minoan palace-site of Phaistos, on

the south coast of Crete, and features 241 tokens, comprising 45 unique

signs, which were apparently made by pressing pre-formed hieroglyphic

"seals" into a disc of soft clay, in a clockwise sequence spiralling

towards the disc's centre.

The Phaistos Disc is generally accepted as

authentic by archaeologists

(2). The assumption of authenticity is based

on the excavation records by Luigi Pernier. This assumption is supported

by the later discovery of the Arkalochori Axe with similar but not

identical glyphs.

(More about the

Phaistos Disc)

| The

Mythology of Knossos: |

Deadalos and Icarus: According to Greek mythology, the palace was

designed by famed architect Deadalos with such complexity that no one

placed in it could ever find its exit. King Minos who commissioned the

palace then kept the architect prisoner to ensure that he would not

reveal the palace plan to anyone. Deadalos, who was a great inventor,

built two sets of wings so he and his son Ikaros could fly off the

island, and so they did. On their way out, Deadalos warned his son not

to fly too close to the sun because the wax that held the wings together

would melt. In a tragic turn of events, during their escape Ikaros,

young and impulsive as he was, flew higher and higher until the sun rays

dismantled his wings and the young boy fell to his death in the Aegean

sea.

The Labyrinth and the Minotaur: The

Labyrinth was the dwelling of the Minotaur in Greek mythology, and many

associate the palace of Knossos with the legend of Theseus

killing the Minotaur. King Minos' son, Androgeus, according to

the myth, was a strong, athletic youth. He was sent to represent Crete

in the Athenian games and was successful in winning many events. The

King of Athens murdered Androgeus out of jealousy. When Minos heard

about the death of his son, he was enraged and deployed the mighty

Cretan fleet. The fleet took Athens and instead of destroying the city,

Minos decreed that every nine years Athens was obligated to send him

seven young men and seven virgin women. King Minos threw them into a

labyrinth where they were sacrificed to the Minotaur. Theseus, the

Athenian King's son, volunteered to be one of the seven sacrificial

young men with the intention of killing the Minotaur and ending the

suffering of Athens. If he succeeded in his mission, he told his father

that he would raise white sails instead of the black sails on his ship. Theseus arrived at the palace of the Cretan King, and with the help of

Minos' daughter, Ariadne (who fell in love with Theseus), he was able to

kill the Minotaur. In returning home, Theseus, in his excitement, forgot

to change the sails on the ship from black to white. The King of Athens

saw the black sails. Thinking that his son's plan failed and that Theseus was dead, the king flung himself into the sea and died.

No labyrinth has been discovered.

(More

about Labyrinths)

| Minoan Art:

Images from Knossos: |

The examples of art from Knossos have been noted for

their non-military content. All were very fragmentary and their

reconstruction and re-placement into rooms by the artist Piet de Jong is

not without controversy.

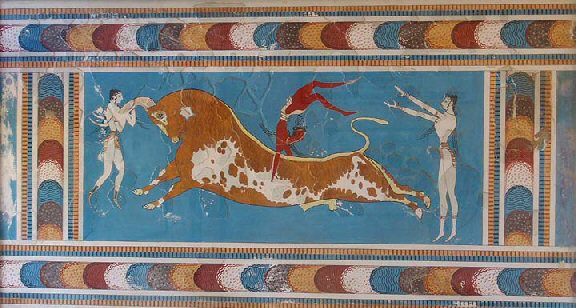

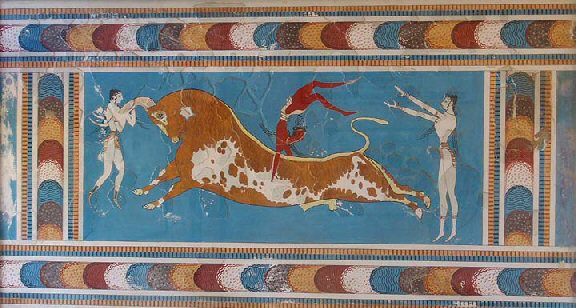

From the Palace of Knossos:

The famous "bull leaping" fresco from the East wing of

the palace.

The different phases of the sport are shown. The bull leapers are both

men and women. 15th century B.C.

The original 32-inch high fresco is in the Iraklio

(or Heraklion) Archaeology Museum.

Dolphin fresco from the palace: Currently suggested to have originally

been on the floor.

|