|

Labyrinths:

Labyrinths:

The word 'Labyrinth' is a pre-Greek word

(Minoan). There is a hidden irony in the current definition and

the original myth of Theseus and the Minotaur's lair, within which one

could get lost in forever. Unlike a maze, which refers to a complex branching puzzle with

choices of path and direction; the 'classic' labyrinth

design has only a single, non-branching path, which

leads to the centre. A labyrinth in this sense has a single,

unambiguous route to the centre and back and is not designed to

be difficult to navigate, so Theseus would have had little need

for Ariadne's thread.

We do not know

when the labyrinth structure first was conceived, but

there are several incidences among the ideograms carved into rock faces across

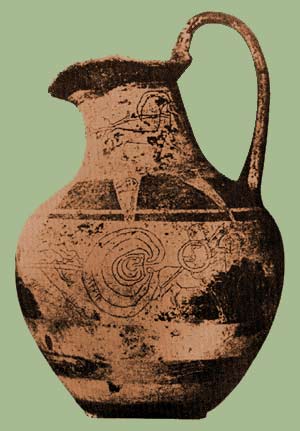

Neolithic and 'Bronze-age' Europe. We see the ideogram later on

an Etruscan vase from c. 550 B.C. Later, at about 300 B.C., it was used on coins in Crete.

During the middle-ages, it was used in European Cathedrals for

pilgrimage.

The Labyrinth as a Spiritual

Tool.

A labyrinth is an

archetype with which we can have a direct experience. We can

walk it. It is a metaphor for life's journey. It is a symbol

that creates a sacred space which leads us into its heart, then

back out again along the same path. Although one is able to

cross the lines at any time, we are compelled to follow the

meandering path to the centre and back again.

The Labyrinth

represents both a journey to our own centre and back out again

into the world... at the same time as acting as a metaphor for

the path we walk throughout our lives.

There is no

getting lost in a Labyrinth. Rather, one is offered a path that

weaves back and forth, in and out, until it ends in a central

circular area. Here, walkers pause to reflect before departing

as they came, carrying back wisdom gained on the inbound

journey. Labyrinth walkers say the certitude of the path�knowing

all decisions about direction have been made�frees them to focus

on contemplation instead of navigation. Some call this prayer;

others, deep reflection. Whatever the name, the practice has

been used to nourish the soul around the world for several

thousand of years.

The Labyrinth

is a powerful geometric symbol with which we have formed an

almost symbiotic relationship, which allows us to enter within

its physical form at the same time as entering into a

non-physical communication with ourselves.

Because they

are so ancient, the various interpretations of the Labyrinth

today may not agree with the same concept of the labyrinths in

ancient times. It is curious then that the same identical symbol

is found in countries and major religious traditions from around

the ancient world (such as India, France, Egypt, Scandinavia,

Crete, Sumeria, America, the British Isles, and Italy), and that

in all cases, they share a common theme of pilgrimage and

spiritual reward. This has led some claim they represent a

universal pattern in human consciousness.

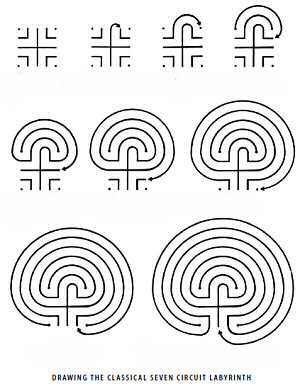

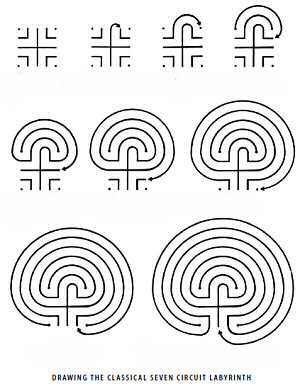

The Geometry of the 'classic'

7-circuit Labyrinth

All 'classic' labyrinths are based on a simple

geometric template.

The ancient

seven-circuit labyrinth (so called because the path creates

seven concentric rings around the centre) is rich with

symbolism. It draws on the mystical quality of the 7, a number

of transformation and vision. In medieval times, the seven

circuits were seen to correspond to the seven visible planets,

and a walk in the labyrinth was a cosmic journey through the

heavens. The seven circuits can also be seen to represent the

days of the week, the chakras, colours, or musical tones.

Some research

suggests that the geometric shape [of a labyrinth] produces an

energy field that can heal ailments of the body and calm the

mind. It balances thoughts with the presence of the body to the

point where one stops thinking and the intuition of knowingness

takes over (4)

Proto Labyrinths..?

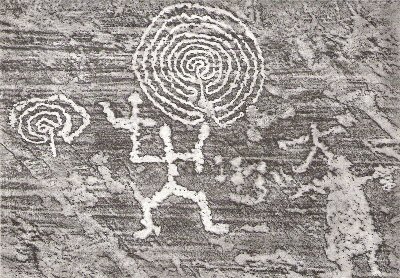

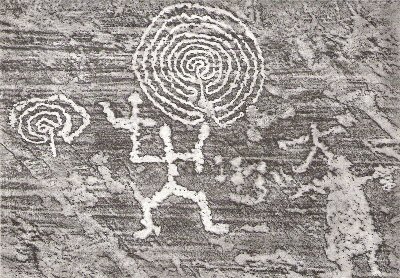

Prehistoric

labyrinths have also been found carved on rock faces at Pontevedra,

Spain and at Val Camonica in northern Italy, these latter ones are

attributed to the late Bronze Age. The Rocky Valley labyrinths in

Cornwall, England, are supposed to be from the Bronze Age. The

labyrinth is found etched into the sands of the Nazca Plain in Peru,

in use among the Caduveo people of Brazil and scratched on boulders

and rockfaces in Northern Mexico, New Mexico and Arizona.

It is suggested

that the Labyrinth evolved from the spiral.

Achnabreck,

Scotland (left), and Knowth, Ireland

(Right).

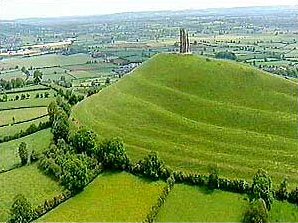

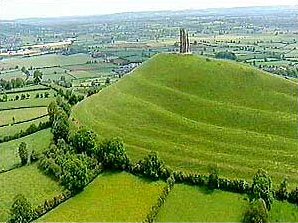

The Glastonbury Labyrinth:

It is proposed that the strong

terracing on the sides of the Tor represent a classic '7-circuit

labyrinth' in three dimensional form.

The Tor is a natural

hill, but it has been established that it was altered in shape from

the late Neolithic onwards. Whether or not the terraces were cut to

replicate the 'classic' Labyrinth shape is still conjectural but the

location, and the tor's reputation as the 'Sacred Heart of England'

makes it possible that the terraces were the final part of a pilgrim

route.

(More

about Glastonbury Tor)

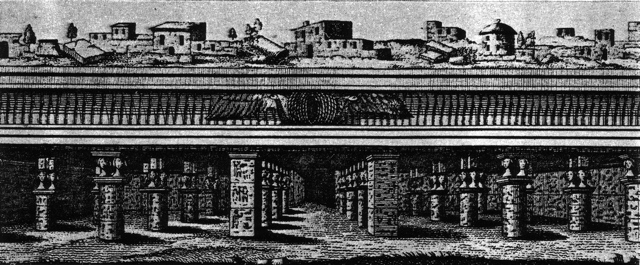

The 'Lost'

Labyrinth of Egypt.

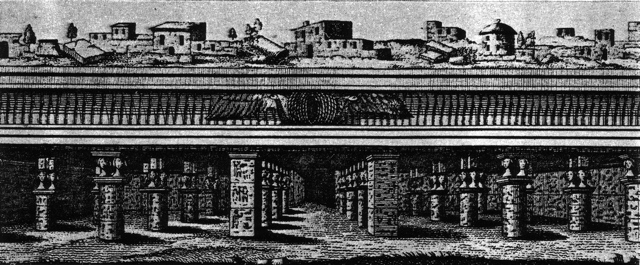

Herodotus (c.

484-424 BC) describes his visit to the now 'lost' labyrinth after

describing how the Egyptians divided the land into twelve parts, or

nomes, and set a king over each, he says that they agreed to

combine together to leave a memorial of themselves. They constructed

the Labyrinth, just above Lake Moeris, and nearly opposite the city

of crocodiles (Crocodilopolis). "I found it," he says, "greater than

words could tell, for, although the temple at Ephesus and that at

Samos are celebrated works, yet all of the works and buildings of

the Greeks put together would certainly be inferior to this

labyrinth as regards labour and expense." Even the pyramids, he

tells us, were surpassed by the Labyrinth. "It has twelve covered

courts, with opposite doors, six courts on the North side and six on

the South, all communicating with one another and with one wall

surrounding them all. There are two sorts of rooms, one sort above,

the other sort below ground, fifteen hundred of each sort, or three

thousand in all." He says that he was allowed to pass through the

upper rooms only, the lower range being strictly guarded from

visitors, as they contained the tombs of the kings who had built the

Labyrinth, also the tombs of the sacred crocodiles. The upper rooms

he describes as being of super-human size, and the system of

passages through the courts, rooms, and colonnades very intricate

and bewildering. The roof of the whole affair, he says, is of stone

and the walls are covered with carvings. Each of the courts is

surrounded by columns of white stone, perfectly joined. Outside the

Labyrinth, and at one corner of it, is a pyramid about 240 feet in

height, with huge figures carved upon it and approached by an

underground passage.

Strabo, who lived

about 400 years after Herodotus also described them first hand.

After referring to the lake and the manner in which it is used as a

storage reservoir for the water of the Nile, he proceeds to describe

the Labyrinth, "a work equal to the Pyramids." He says it is "a

large palace composed of as many palaces as there were formerly

nomes. There are an equal number of courts, surrounded by

columns and adjoining one another, all in a row and constituting one

building, like a long wall with the courts in front of it. The

entrances to the courts are opposite the wall; in front of these

entrances are many long covered alleys with winding

intercommunicating passages, so that a stranger could not find his

way in or out unless with a guide. Each of these structures is

roofed with a single slab of stone, as are also the covered alleys,

no timber or any other material being used." If one ascends to the

roof, he says, one looks over "a field of stone." The courts were in

a line, supported by a row of twenty-seven monolithic columns, the

walls also being constructed of stones of as great a size. "At the

end of the building is the royal tomb, consisting of a square

pyramid and containing the body of Imandes." Strabo says that

it was the custom of the twelve nomes of Egypt to assemble, with

their priests and priestesses, each nome in its own court,

for the purpose of sacrificing to the gods and administering justice

in important matters.

(More

about the 'Lost' Labyrinth of Egypt)

The Minoan Labyrinth,

Crete:

In Greek

mythology, the Labyrinth was an elaborate structure designed and

built by the legendary craftsman Daedalus for King Minos of

Crete at Knossos to conceal the Minotaur.

'At that

time there reigned at Knossos, in Crete, a monarch called Minos,

who held sway over what was then the most powerful maritime

state in the Mediterranean. Minos had a son named Androgeos,

who, during his travels in Attica, was treacherously set upon

and slain, or so his father was informed. In consequence of this

Minos imposed a penalty on the Athenians in the form of a

tribute to be paid once every nine years, such tribute to

consist of seven youths and seven maidens, who were to be

shipped to Knossos at the appointed periods.

There was at

the court of Minos an exceedingly clever and renowned artificer

or engineer, Daedalus by name, to whom all sorts of miraculous

inventions are ascribed. This Daedalus had devised an ingenious

structure, the "Labyrinth," so contrived that if anybody were

placed therein he would find it practically impossible to

discover the exit without a guide.

The

Labyrinth was designed as a dwelling for, or at any rate was

inhabited by, a hideous and cruel being called the Minotaur, a

monstrous offspring of Queen Pasipha�, wife of Minos. The

Minotaur is described as being half man and half bull, or a man

with a bull's head, a ferocious creature that destroyed any

unfortunate human beings who might come within its power.

According to report, the youths and maidens of the Athenian

tribute were periodically, one by one, thrust into the

Labyrinth, where, after futile wanderings in the endeavour to

find an exit, they were finally caught and slain by the

Minotaur'. (1)

There are many

versions of the legend, some of them greatly at variance with

others. For instance, Philochorus, an eminent writer on the

antiquities of Athens, gives in his "Atthis" a very rationalistic

account of the affair, stating that the Labyrinth was nothing but a

dungeon where Minos imprisoned the Athenian youths until such time

as they were given as prizes to the victors in the sports that were

held in honour of his murdered son. He held also that the monster

was simply a military officer, whose brutal disposition, in

conjunction with his name, Tauros, may have given rise to the

Minotaur myth.

These 5th - 3rd

century BC coins from Knossos were struck with the labyrinth

symbol. The predominant labyrinth form during this period is the

simple 7-circuit style known as the classical labyrinth.

(More

about Knossos, Crete)

The Nazca Labyrinth:

A five-year

study by British archaeologists has shed new

light on the enigmatic drawings created by

the Nazca people between 100 BC and CE 700

in the Peruvian desert. They discovered an

itinerary so complex they can justify

calling it a labyrinth, and see it as

serving ceremonial progressions.

In the midst

of the study area is a unique labyrinth

originally discovered by Prof Ruggles when

he spent a few days on the Nazca desert back

in 1984. �When I set out along the labyrinth

from its centre, I didn�t have the slightest

idea of its true nature,� Prof Ruggles

explained. �Only gradually did I realize

that here was a figure set out on a huge

scale and still traceable, that it was

clearly intended for walking. Invisible in

its entirety to the naked eye, the only way

of knowing its existence is to walk its 2.7

miles (4.4 km) length through disorienting

direction changes which ended, or began,

inside a spiral formation.

(Link

to Full Article)

�The labyrinth is

completely hidden in the landscape,

which is flat and virtually

featureless. As you walk it, only

the path stretching ahead of you is

visible at any given point.

Similarly, if you map it from the

air its form makes no sense at all.�

�But if you walk

it, discovering it as you go, you

have a set of experiences that in

many respects would have been the

same for anyone walking it in the

past. The ancient Nazca peoples

created the geoglyphs, and used

them, by walking on the ground.

Sharing some of those experiences by

walking the lines ourselves is an

important source of information that

complements the hard scientific and

archaeological evidence and can

really aid our attempts to make

anthropological sense of it.�

This ground shot is taken along the innermost pathway of the labyrinth directly

towards the central mound.

The line widens out towards its terminus, creating a

false perspective that makes it appear parallel as it stretches away into the

distance.

(Photo

Credit: Clive Ruggles)

(More

about The Nazca Lines)

The Labyrinth and the

Church.

Probably the oldest

known example of this nature is that in the ancient basilica of

Reparatus at Orl�ansville (Algeria), an edifice which is

believed to date from the fourth century A.D.

(1)

It measures about 8 ft. in diameter and shows great resemblance to

the Roman pavement found at Harpham and the tomb-mosaic at Susa. At

the centre is a jeu-de-lettres on the words SANCTA ECLESIA,

which may be read in any direction, except diagonally, commencing at

the centre. But for the employment of these words the labyrinth in

question might well have been conceived to be a Roman relic utilised

by the builders of the church to ornament their pavement. Such

pavement-labyrinths, however, with or without central figures or

other embellishments, and of various dimensions and composition, are

found in many of the old churches of France and Italy.

As to the function

and meaning of the old church labyrinths, various opinions have been

held. Some authorities have thought that they were merely introduced

as a symbol of the perplexities and intricacies which beset the

Christian's path. Others considered them to typify the entangling

nature of sin or of any deviation from the rectilinear path of

Christian duty. It has often been asserted, though on what evidence

is not clear, that the larger examples were used for the performance

of miniature pilgrimages in substitution for the long and tedious

journeys formerly laid upon penitents. Some colour is lent to this

supposition by the name "Chemin de J�rusalem." at Chartres (see

below). In the days of the first crusades it was a common practice

for the confessor to send the peccant members of his flock either to

fight against the infidel, or, after the victory of Geoffrey of

Bouillon, to visit the Holy Sepulchre. As enthusiasm for the

crusades declined, shorter pilgrimages were substituted, usually to

the shrine of some saint, such as Our Lady of Loretto, or St. Thomas

of Canterbury, and it is quite possible that, at a time when the

soul had passed out of the crusades and the Church's authority was

on the ebb, a journey on the knees around the labyrinth's

sinuosity's was prescribed as an alternative to these pilgrimages.

Perhaps this type of penance was from the first imposed on those

who, through weakness or any other reason, were unable to undertake

long travels.

This view seems to

rest chiefly on a statement by J. B. F. G�ruzez in his "Description

of the City of Rheims" (1817), to the effect that the labyrinth

which formerly lay in the cathedral was in origin an object of

devotion, being the emblem of the interior of the Temple of

Jerusalem, but G�ruzez quotes no authority for his assertion.

Another explanation, based upon the occurrence of the figures of the

architects or founders in certain of the designs, is that the

labyrinth was a sort of masonic seal, signifying that the pious aim

of the builder had been to raise to the glory of God a structure to

vie with the splendours of the traditional Labyrinth. It is also

said that in some cases the "Chemins" were used for processional

purposes.

Some writers have

held that the labyrinth was inserted in the church as typifying the

Christian's life or the devious course of those who yield to

temptation. Some have thought that it represented the path from the

house of Pilate to Calvary, pointing out that Chateaubriand, in his

"Itin�raire de Paris � J�rusalem," mentioned two hours as the period

which he took to repeat Christ's journey, and that the same time

would be taken in traversing the average pavement labyrinth on the

knees.The use of the labyrinth as a simile for the Christian's life

is shown in a stone inscription in the Museum at Lyons:

(1)

Chartres,

France: Chartres,

France:

There have been at

least five cathedrals on this site, each replacing an earlier

smaller building that had been destroyed by war or fire. It was

called the 'Church of Saint Mary' in the eighth century.

One of the best

known examples of Cathedral Labyrinths is found at Chartres, in

rance: As well as the huge 11-circuit labyrinth on the floor,

the cathedral has a spectacular rose window over the great west

doors. This has the same dimensions as the labyrinth and is exactly

the same distance up the west wall as the labyrinth is laterally

from the cathedral's main entrance below the window

The labyrinth at Chartres was known as a "Chemin

de J�rusalem" "daedale," or "meandre," terms which

need no explanation. The centre was called "ciel" or "J�rusalem."

(1)

When pilgrimage to

the Holy City of Jerusalem was made difficult and dangerous by the

Crusades. The Church designated seven European cathedrals, mainly in

France, to become �Jerusalem� for pilgrims. The labyrinth became the

final stage of pilgrimage, serving as a symbolic entry into the

Celestial City of Jerusalem. All seven cathedrals used the

11-circuit labyrinth design.

(3)

Other Examples

of Labyrinths from around the Ancient World.

Although it is

difficult to date exactly, this (Neolithic - Early Bronze-age)

labyrinth comes from Val Camonica, in Italy. The Val Camonica

valley has revealed over 300,000 petroglyphs of which this is

just one. It is one of the richest sources of rock-art in all

Europe.

(More

about Val Camonica, Italy)

Reverse of a

clay tablet from Pylos bearing the motif of the Labyrinth. The

tablet, the earliest datable representation of the 7-course

classical labyrinth, was recovered from the remains of the

Mycenaean palace of Pylos, destroyed by fire ca 1,200 B.C. (Kern,

Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, p. 73, catalog item

103�104).

(More

about Mycenae, Greece)

This classic

'3-circuit labyrinth' is one of the many intricate geoglyphs,

or patterns created on the plains northwest of Nazca, Peru,

by the indigenous peoples there, sometime between 200 B.C. and 700

A.D. Native Americans had them, and continue to be used in the

sacred ceremonies of the Hopi. The Hopi Indians called the

labyrinth the symbol for �mother earth� and equated it with the

Kiva (called it Tapu'at, or Mother-child.)

(More

about Nazca, Peru)

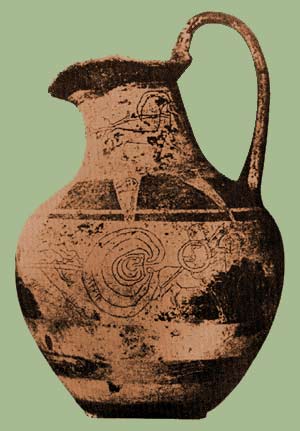

This Etruscan

Vase (c. 550 B.C.) came from Tragliatelli, Italy, with labyrinth

design and three horse-back warriors riding away from it.

Currently the earliest evidence

for the labyrinth in Asia is probably a labyrinth carved amongst

other prehistoric petroglyphs, recently discovered on a

riverbank at Pansaimol in Goa (Kraft, 2005). The age of this

labyrinth is the subject of considerable dispute amongst experts

on Indian rock art, but it could date to the Neolithic period,

maybe c. 2,500 B.C. which would make it as old, if not older, than

similar early labyrinth petroglyphs in Europe. Several examples

of the labyrinth symbol have also been found amongst cave art in

the north of India. One example at Tikla, in Madhya Pradesh, has

been dated to approximately 250 B.C., although doubt remains as

to whether the labyrinth is contemporary with other more

dateable figures (Kern, 2000).

(2)

(Prehistoric

India)

(Knossos,

Greece) (The

'Lost' Labyrinth, Egypt)

(Spirals)

(Sacred

Geometry)

(Altered

Landscapes)

|

Chartres,

France:

Chartres,

France: