|

Landscape Zodiacs (Mandalas):

Landscape Zodiacs (Mandalas):

A landscape zodiac

(or terrestrial zodiac) is a map of the stars on a gigantic

scale, formed by features in the landscape, such as roads, streams

and field boundaries. Perhaps the best known alleged example is the

Glastonbury

'Temple of the Stars', situated around

Glastonbury in

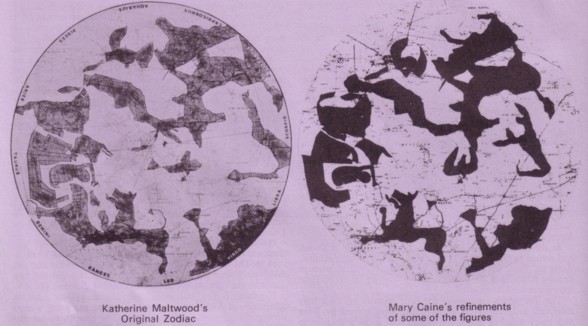

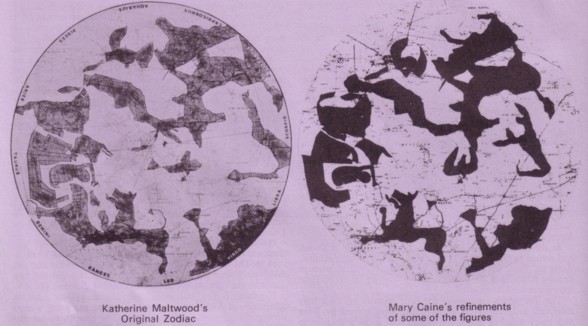

Somerset, England. The Glastonbury Zodiac was first described by the artist, Katharine Maltwood

in the 1920s, and has remained controversial ever since, even though over fifty

more zodiacs have been since described in Britain and Europe. The

focus of the question appears to no longer be whether these

mysterious zodiacs exist - but rather, how and why they do.

The

idea that the heavens were mapped around Glastonbury

is not a new one. It is said for example, that

Katherine Maltwood's revelations had been fed by her

remembering reading 'the 13th century antiquarian

William of Malmesbury's gnomic comment that

Glastonbury was a "heavenly sanctuary on Earth."

(6)

The

occultist Dr. John Dee, following Druidic/Hermetic

traditions, made several visits to the area around

1580 from which he prepared charts and a commentary

regarding what he called 'Merlin's Secret' around

Glastonbury. Dee had noted the unusual arrangements

of prehistoric earthworks in the Glastonbury area,

as Richard Deacon, his 20th century biographer

notes. (6)

He makes clear mention of the way they apparently

represented the constellations of the Zodiac in the

following sentence:

"The Starres which

agree with their reproductions," Dee wrote, "on

the ground do lye onlie on the celestial path of

the sonne, moon and planets...thus is astrologie

and astronomie carefullie and exactley married

and measured in a scientific reconstruction of

the heavens which shews that the ancients

understode all whic today the lerned know to be

facts."

Glastonbury was mentioned as one of 'Britain's

Perpetual Choirs'

in the 1796 edition of a translation of FABLIAUX

(TALES) which includes a four line Welsh text (known

as a Triad - or 'triade'), and an English

translation of it. The theme is the Perpetual Choirs

of Britain, and the three sites given in the

translation are the 'Isle of Avalon'

(Glastonbury), 'Caer Caradoc' (Salisbury) and 'Bangor

Iscoed' (Disputed). (7)

In 1801, Iolo Morganwg

recorded that 'in each of these choirs there were

2,400 saints; that is there were a hundred for every

hour of the day and the night in rotation,

perpetuating the praise and service of God without

rest or intermission.' The function of the

choirs was to maintain the enchantment and peace of

Britain. John Michell later adopted this into his

concept of a vast landscape 'Decagon'. (see below)

The theory was next

brought to light in 1929 by

Katherine Maltwood, a Canadian artist who was

researching landscapes around Glastonbury to

illustrate a book, when she 'realised' the

zodiac in a vision.

The

Glastonbury

'Zodiac' was 'refined' by Mary Caine in the 1960's, and

has been expanded upon since.

Criticism: The idea was

examined by two independent studies, one by Ian Burrow

in 1975 and the other in

1983 by Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy,

using standard methods of landscape historical

research. Both studies concluded that the evidence

contradicted the idea. The eye of Capricorn identified

by Maltwood was a haystack. The western wing of the

Aquarius phoenix was a road laid in 1782 to run around

Glastonbury, and older maps dating back to the 1620s

show the road had no predecessors. The Cancer boat (not

a crab as would be expected) is made up of a network of

eighteenth century drainage ditches and paths. There are

some Neolithic paths preserved in the peat of the bog

formerly comprising most of the area, but none of

the known paths match the lines of the zodiac

features. There is no support for this theory, or

for the existence of the "temple" in any form, from

conventional archaeologists or mainstream

historians. (1)

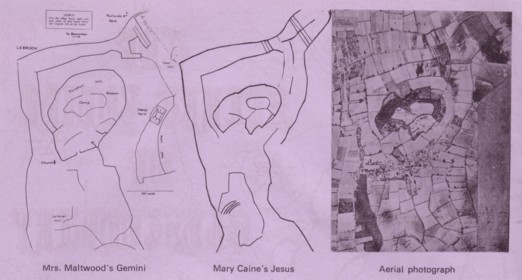

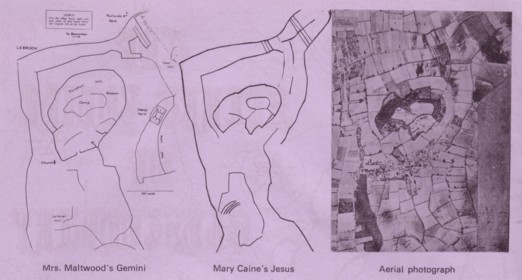

Which of these images matches

Gemini.

The biggest

problem with Katherine Maltwood�s discovery is

that she used features seen in the present-day

landscape. Some of the details are derived from

roads and field boundaries that can be

demonstrated not to have existed before the

nineteenth century. Some, which she and her

followers identified from aerial photographs

have turned out to be signs of agricultural

activity at the time the photographs were taken

(such as the �eye� of Capricorn, which was a

haystack)! Even then, the figures do not

correspond to the traditional figures of the

zodiac as we know it: The Image for Gemini is

now said to be a figure of 'Jesus', and Cancer, for instance, is

not a crab but a ship. And yet the �Glastonbury

Zodiac� is supposed to be the best attested and

most convincing of such �monuments�.

Anthony Thorley has

more recently identified over fifty Zodiacs across the British countryside and has researched the

subject in depth. It is perhaps his mention of an acausal relationship

between the consciousness of humanity and the landscape that offers

something of a glimmer of hope in trying to understand the process

that seems to be occurring here as, seemingly in collusion with

human consciousness, the British landscape appears to have

'manifested' over 50 gigantic zodiac simulacra of zodiac symbols,

'mostly

emblematic animals, in the shapes of its natural and its cultured

landscape'. Moreover, these symbols are said to appear in the same order as their

star signs around the ecliptic.

While it is

true that most of these 'zodiacs' are open to the same intrinsic

criticisms as the esteemed Katherine Maltwood's 'Temple of the

Stars' at Glastonbury, their presence opens the debate of the

existence of an dialogue between the cosmos and what Jung called

the 'collective unconscious'.

Other Examples of

Landscape Zodiacs:

The Kingston

Zodiac, London. - Mary Caine. The Kingston

Zodiac, London. - Mary Caine.

(Image right: From 'The Kingston Zodiac, by Mary

Caine, 1978).

The Walsingham

Zodiac, Norfolk. St. Mary's Shrine. -

Stephen Jenkins.

The

Canterbury Zodiac, UK - 'Fen-lander': (http://fen-lander.hubpages.com/)

The Sussex

Zodiac. - Mike Collier.

Should it be

determined through future investigation that zodiacs (or

mandalas) are - as it is suggested, 'manifesting' themselves onto

the landscape without conscious intervention, then it becomes

reasonable to propose that this might be evidence of the

existence of the primitive umbilical connection

between us and the living-landscape. Should such a phenomena

exist in the west, as it is still practiced and believed to in

the orient, then regardless of the specifics and accuracy of

these zodiacs, by recognising them we have

entered back into the ancient and almost lost acausal narrative

between people and their landscapes, between our unconscious

imaginations and the cosmic structure of all things.

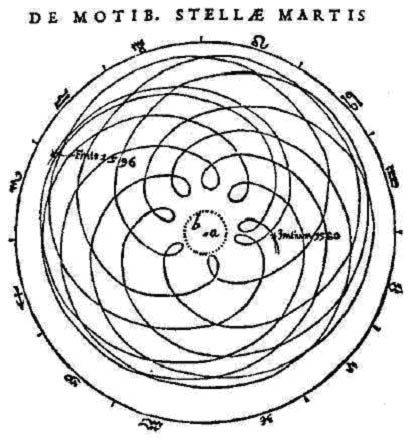

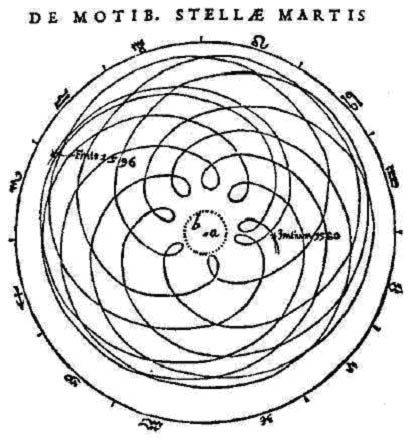

There is no doubting the fact that we

live within a universe that operates on a geometric basis. The motions

of the planets have long been known to follow mathematical

rules, which has enabled us to predict and understand the

motions of the heavens to the degree we do today. In Europe, it was the great Johannes

Kepler, also responsible for the re-discovery of the

'Harmony of the Spheres', who delved most deeply into the geometric nature of the orbits of planets and stars. In

Kepler�s monumental work Astronomia Nova (The New Astronomy)

in 1609 he described the intensive work that finally

resulted in his discovery of the elliptical orbits of planes

the laws of planetary motion. In this book he also drew the

following

drawing of the orbit of Mars from the Earth�s point of view.

This extraordinary step in thinking is still a long way from the

mandalas of Buddhist and Hindu cultures, which represent the

whole cosmos within the perfection of geometry.

(More

About The

Harmony of the Spheres)

Mandalas have a

ritual and spiritual significance in both Buddhist and Hindu beliefs

where they are highly regarded, and used as meditative and spiritual

'tools' or 'guides' for initiates on the path to wisdom. Martin Gray

(5) provides

examples of Buddhist 'Landscape Mandala's', highlighting that sacred

places are located according to various mythological, symbolic,

astrological, and Shamanic factors. Mandala's are generally considered to

be two

dimensional representations of the cosmos, through geometric designs, but

the

Japanese Shingon Buddhists project Mandalas over large

geographical areas, as symbolic representations of the residence

of Buddha. Gray explains:

'The

Mandalas were projected upon a number of pre-Buddhist

(Shinto) and Buddhist sacred mountains, and the practice of

monks and pilgrims was to travel from peak to peak,

venerating Buddha's and bodhisattvas residing in them. the

passage through the landscape Mandala's was made according

to a specific and circuitous route. Ascents of the sacred

mountains were conceived of as metaphorical ascents through

the world of enlightenment'.

Borobudur,

Indonesia: Mandala bridging the gap between 2-dimensional art and

3-dimensional cosmology.

Gray

continues to say that 'the architects of these vast terrestrial

Zodiacs made their landscape a living image of the heavens'.

(2).

In fact, it is has been shown that the major Buddhist shrines, monasteries, etc. of Japan, China and

Tibet were placed within the much wider geographic context of

natural terrain to both create spiritual focus and to take

advantage of the energetic power forms in nature. The intended

effect was not only to build in auspicious places, but to

position the shrines within immense natural mandalas of form and

power. (3) Gray

continues to say that 'the architects of these vast terrestrial

Zodiacs made their landscape a living image of the heavens'.

(2).

In fact, it is has been shown that the major Buddhist shrines, monasteries, etc. of Japan, China and

Tibet were placed within the much wider geographic context of

natural terrain to both create spiritual focus and to take

advantage of the energetic power forms in nature. The intended

effect was not only to build in auspicious places, but to

position the shrines within immense natural mandalas of form and

power. (3)

Carl Jung is said to have

recognised that the Mandala symbolically represented the 'self', but

the classical development of mandalas as meditative tools,

constructed according to particular aesthetic criteria, emerged in

India, specifically in Hinduism and later in Buddhism. Iconographic

forms similar to the mandala in construction and sometimes in

interpretation and purpose have been developed in other cultures,

but the literature currently available suggests that it was in

Hinduism and Buddhism that they achieved their most precise and

elaborate characterisation as cognitive tools. Within these

religious cultures, the mandala was most often understood as a

cosmographic representation which would assist the contemplative

achieve a cognitive identification with the metaphysical structure

and dynamism of the cosmos. (4)

In recognising this process, we are again reminded of the

possibility that such identification implies an element of

conjunction between cosmic structure and the structure of human

consciousness.

John Michell:

The theme of a

metaphysical geometric landscape arrangement is reminiscent of John Michel's discovery of

a 'Great Decagon'

across the British Landscape. It is a curious but nevertheless

factual statement that the three most important southern English

sites (Glastonbury, Stonehenge and Avebury/Silbury) are connected

through geometry accurate to 1 part in 1/000. As well as both

Glastonbury and Avebury/Silbury lying on the St. Michael's Leyline,

Glastonbury and Stonehenge are also 'nodes' on a vast landscape

'mandala/decagon' centred on

Whiteleaved Oak. Michell's attention was drawn back to

Glastonbury more than once as he became immersed in the legends and

geometry of prehistoric Britain. One of his most notable discoveries

was the proposal of a spiritual and physical 'Decagon' across the

landscape. His research led him to the 1796 texts of which spoke of

'perpetual choirs', or holy locations from which the eternal chanting of monks

maintained both the heavens, and the spiritual harmony of the

people. This vast geometric figure, (or at least the basis of one),

he realised, encompassed at

least two of the most spiritual places in Britain. (Glastonbury and

Stonehenge), The

1801 text by Iolo Morganwg added that

'in each of these choirs there were 2,400 saints; that is there

were a hundred for every hour of the day and the night in rotation,

perpetuating the praise and service of God without rest or

intermission.' The function of the choirs was to maintain the

enchantment and peace of Britain and the connection between human

consciousness and the landscape in this myth shows a clear

similarity to the Buddhist and Hindu traditions of forming landscape

Mandalas.

John Michell also

wrote at length on the subject of the tradition of a 'New Jerusalem'

being both a physical and spiritual reality. He came to believe that

Glastonbury was the 'celestial city' described and proposed in the

bible, following on the tradition that Joseph of Arimathea brought

more than just Christianity to Britain (Glastonbury), as in the 12th

century he became known as the first holder of the Grail. The concept

of a 'New Jerusalem' wasn't, in Michell's opinion, just a schematic

for a city. He was aware that while it has its origins in the text

in Revelations (Rev 21,12) which mentions the '...12 gates of the

celestial city..', it also enigmatically describes the

dimensions of the city as a perfect cube with length, width, and

height of 12,000 furlongs (fifteen hundred miles). A cube of course,

is hardly the ultimate design for a 'heaven on earth', and

there has been much work on the idea that such references are purely

symbolic, although interestingly, Michell used this as the

centre-piece for a Mandala he designed of New Jerusalem.

(More

about the Great Decagon)

Gallery of Images: Mandalas on the

Landscape.

The

'Forbidden City', Peking. Designed c. 1406 -1420.

Palmanova, Italy.

Designed 1593.

Canberra,

Australia. Designed 1913.

Nazca Mandala,

Peru. Origin Unknown.

(Simulacrum)

(Earth

Energies)

(Altered

Landscapes)

(Geometric

Alignments)

(The

Origin of the Zodiac)

|

Gray

continues to say that 'the architects of these vast terrestrial

Zodiacs made their landscape a living image of the heavens'.

(2).

In fact, it is has been shown that the major Buddhist shrines, monasteries, etc. of Japan, China and

Tibet were placed within the much wider geographic context of

natural terrain to both create spiritual focus and to take

advantage of the energetic power forms in nature. The intended

effect was not only to build in auspicious places, but to

position the shrines within immense natural mandalas of form and

power. (3)

Gray

continues to say that 'the architects of these vast terrestrial

Zodiacs made their landscape a living image of the heavens'.

(2).

In fact, it is has been shown that the major Buddhist shrines, monasteries, etc. of Japan, China and

Tibet were placed within the much wider geographic context of

natural terrain to both create spiritual focus and to take

advantage of the energetic power forms in nature. The intended

effect was not only to build in auspicious places, but to

position the shrines within immense natural mandalas of form and

power. (3)