|

The Etruscans:

(Tyrrhenians)

The Etruscans:

(Tyrrhenians)

The Etruscan

civilization is the modern English name given to the ancient Italian

civilisation in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany

(Apparently composed of 12 cities). The ancient Romans who followed

them historically, called its creators the Tusci or

Etrusci.

The Etruscan

civilisation, as distinguished by

its unique language, endured at least from the

time of the earliest Etruscan inscriptions (c. 700 BC) until its

assimilation into the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC

(1)

|

The

Origin of the Etruscans: |

The origin of the

Etruscans has been a subject of debate since antiquity.

Herodotus (c. 430 BC) said for

example that the Etruscans came from Lydia, in Asia Minor, as

the result of a famine around 1,200 B.C,

establishing

themselves over the native inhabitants of the region

(Histories 1.94),

whereas Dionysius of

Halicarnassus (c. 30 B.C.) quoted an earlier historian,

Hellanicus (contemporary of Herodotus), who objected to the

Lydian origin theory on the basis of differences between Lydian

and Etruscan languages and institutions. For Hellanicus, the

Etruscans were Pelasgian's from the Aegean.

Dionysius (Roman antiquities 1.30.2) himself believed

that the Etruscans were of local Italian origin.

Recent DNA research appears to

show that at least part of the Etruscan population was related

to people in Asia Minor (4),

similar DNA tests on goats and cattle suggest Herodotus may have

been the more correct of the three.

(3)

Herodotus: 'Histories', 1.94:

'The Lydians have very nearly the same customs as the

Hellenes, with the exception that these last do not bring up

their girls the same way. So far as we have any knowledge,

the Lydians were the first to introduce the use of gold and

silver coin, and the first who sold good retail. They claim

also the invention of all the games which are common to them

with the Hellenes. These they declare that they invented

about the time when they colonized Tyrrhenia [i.e.,

Etruria], an event of which they give the following account.

In the days of Atys the son of Manes, there was great

scarcity through the whole land of Lydia. For some time the

Lydians bore the affliction patiently, but finding that it

did not pass away, they set to work to devise remedies for

the evil. Various expedients were discovered by various

persons: dice, knuckle-bones, and ball, and all such games

were invented, except checkers, the invention of which they

do not claim as theirs. The plan adopted against the famine

was to engage in games one day so entirely as not to feel

any craving for food, and the next day to eat and abstain

from games. In this way they passed eighteen years.

Still the affliction continued,

and even became worse. So the king determined to divide the

nation in half, and to make the two portions draw lots, the

one to stay, the other to leave the land. He would continue

to reign over those whose lot it should be to remain behind;

the emigrants should have his son Tyrrhenus for their

leader. The lot was cast, and they who had to emigrate went

down to Smyrna, and built themselves ships, in which, after

they had put on board all needful stores, they sailed away

in search of new homes and better sustenance. After sailing

past many countries, they came to Umbria, where they built

cities for themselves, and fixed their residence. Their

former name of Lydians they laid aside, and called

themselves after the name of the king's son, who led the

colony, Tyrrhenians'.

(Article: Feb, 2007. The Telegraph:

Genes Prove Herodotus Right)

The Decline of the Etruscans

By around 500 BC,

Rome had become the most important city on the central Italian

mainland. This allowed it to shrug off its masters, the

Etruscans, who worked for so long to make Rome what it was.

After losing control of Rome to the south, they strengthened

their naval power through an alliance with Carthage against

Greece. In 474 BC their fleet was destroyed by the Greeks of

Syracuse. From that time their power rapidly declined. The Gauls'

overran the country from the north, and the Etruscans' strong

southern fortress of Veii fell to Rome after a ten-year siege

(396 BC), following which the Etruscans were absorbed by the

Romans, who adopted many of their advanced arts, their customs,

and their institutions.

The end of the

Etruscan civilisation is dated at 54 AD. The same year that

Emperor Claudius, the great lover of the Etruscan civilisation

and husband of the Etruscan princess Urgulanilla died. Claudius

was supposedly the last speaker of the ancient language and used

his access to the private libraries to write 20 books entitled "Tyrrhenika"

on the history of the Etruscan people (now lost).

Contemporary reports from

Greeks and Romans tell us that the Etruscans were an educated

people with a range of literature, including religious and

historic texts. Sadly, as was the

case with the Mayan codices, almost all the literature was burnt

by the Romans.

There is evidence that a significant portion of

Etruscan literature was systematically destroyed following the

Theodosian code, since it represented the Old Religion and was

considered as idolatry and the work of the devil. (It is recorded

that Flavius Stilicho, a regent for the Emperor Honorius between 394

and 408 CE, burnt a number of "Pagan volumes" which included the

Tagetic books, which had been stored in the Temple of Apollo in

Rome.) However there are other probable reasons that led to the

demise of Etruscan literature. The question of the scope of Etruscan

literature remains unanswered, but it is quite clear from other

sources that it must have been quite substantial. Censorinus refers

to the Annals of Etruria, and during the late Roman Republic and

Early Imperial years it was considered quite fashionable for Roman

Patricians to send their boys to Etruscan schools to further their

education. Some of this would no doubt have been a grounding in the

disciplina etrusca, but it seems unlikely that that was all that

they learned. We also know that enough of the history of Etruria

survived in written form even up to late Imperial times for the

emperor Claudius to write his twenty volume history of Etruria.

(2)

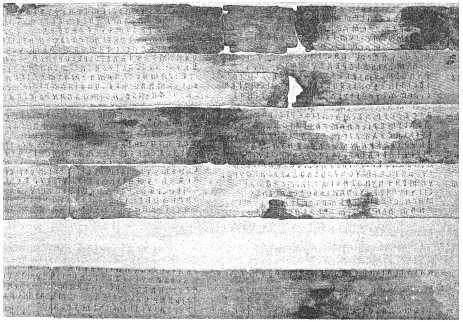

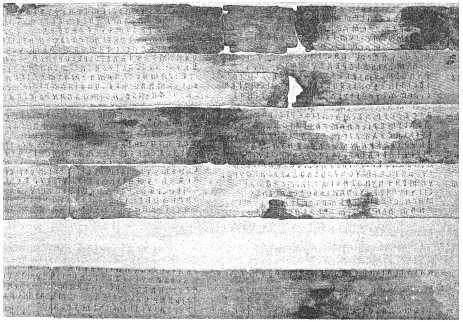

Regardless of this, a corpus of over 10,000 known Etruscan

inscriptions remain, with new ones being discovered each year. These

are mainly short funerary or dedicatory inscriptions, found on

funerary urns, in tombs or on objects dedicated in sanctuaries.

Others are found on engraved bronze Etruscan mirrors, where they

label mythological figures or give the name of the owner, and on

coins, dice, and pottery. Finally, there are graffiti scratched on

pottery; though their function is little understood, they seem to

include owners' names as well as numbers, abbreviations, and non

alphabetic signs.

Although we know the sounds of the

letters, we do not understand the words.

Archaic Etruscan: (7th - 5th centuries BC)

Neo-Etruscan: (4th-3rd centuries BC).

Examples of

Etruscan Texts.

The longest

surviving Etruscan text today: The 'Liber Linteus'

In 1848 or 1849, a

nobleman from Slovenia, Mihail de Baric, bought a mummy in Egypt,

which found its way into the National Museum of Zagreb in 1862.

Where the mummy had been found and sold is unknown. The mummy

consisted of the remains of a child. It was wrapped in a piece of

linen cloth, which had been torn into wrapping binds. The linen

cloth had been written on with texts in ink, apparently before it

was torn into pieces and used as mummy wrapping. At first it was

thought that the texts were a literal transcription from a text in

Egyptian. In 1891, the Austrian Egyptologist J. Krall discovered

that the linen consisted of Etruscan text.

These Gold plates

(The Pyrgi Lamellae) were written in both Etruscan and Phoenician.

They record a dedication to the Goddess called Astarte.

Etruscan Metallurgy.

Etruscan metalwork was highly regarded and

imported by the Greeks and north Europeans. Several elaborate bronze

pieces (tripods, bronze mirrors, cauldrons, pails and wine jugs),

dating from the seventh to fifth centuries BC, have been found in

many locations, including England and Scandinavia.

The Chimaera from

Arezzo (C. 500 BC).

Other surviving examples of Etruscan metal sculpture include a

sheet-hammered bust of a woman from Vulci (circa 600 BC), a

charioteer from Monteleone (circa 540 BC), the Apollo of Veii (circa 600 BC), a war god (circa

450 BC) and the Warrior (circa 350 BC). The Capitpline Wolf, the

symbol of Rome, is also believed to be Etruscan, dating from about

500 BC.

(More examples of Prehistoric Metallurgy)

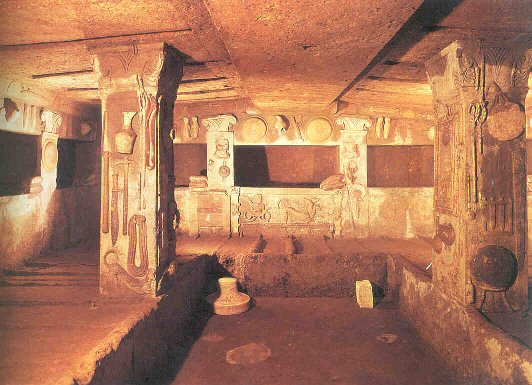

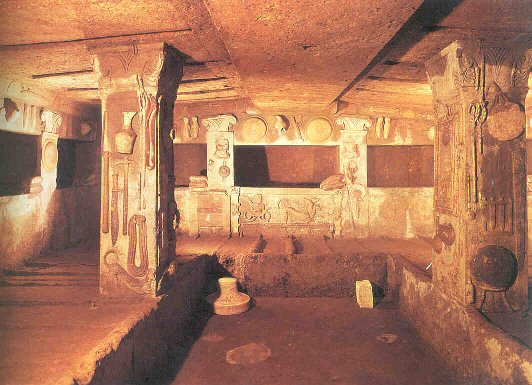

The Afterlife: Tomb Building.

The importance of the afterlife to the

Etruscans is best illustrated in the valley of

Cervtari, Etruscan tombs

can be found. Within it lies the Necropolis Della Banditacca,

The necropolis is a city of the dead. On either side of a "main

street" some 2km/1.5miles long, with a number of side streets, lie

hundreds of tombs, including huge tumuli up to 30m/99ft in diameter

and many tomb chambers hewn from the rock in the form of

dwelling-houses, often with several rooms, with frescoes like the

Tomb of Rilievi decorated with plaster relief's of mythological

figures.

The tombs at Tarquinia and Cerveteri

are particularly interesting because they are of the chamber type: a

large mound would be piled on top of a circular wall with an

entrance to it. The entrance would often lead downwards into a

passageway and into a number of chambers, rather like a house. The

one in the image below is particularly well known for the large

number of relief sculptures showing the different types of

implements and tools one would have had in one's own home at the

time. This tomb is also interesting for the ceiling, which has

obviously been sculpted to mimic the ceiling of housing of the time.

Divination:

Etruscan priests made sacrifices to the gods and

practiced haruspicy (hetacoscopy), or the art of divining the will

of the gods by observing the livers of sacrificed animals, the

patterns of lightning, and the flight of birds. All their methods of

divination were carefully followed by the Romans for centuries

after.

Chalchas the

seer, divining a liver on a bronze (5th cent BC) Etruscan mirror. His

wings and feet demonstrating the symbolic connection of seers

between men and the gods.

(Vatican: Gregorian Museum, Rome, cat #

12240)

The Etruscan discipline of divining

from liver inspection shows remarkably

close correspondence to the form of divination developed in

Mesopotamia and this can best be explained as the transmission of a

�school� from Babylon to Etruria. The correspondence between

Etruscan and Assyrian hepatoscopy is evident when one compares the

Etruscan bronze liver found at Piacenza with the Mesopotamian clay

models (see below). The system on the slaughter of sheep, the models of sheep

livers from clay and metal and the custom of providing them with

inscriptions for the sake of explanation, is something peculiar

found precisely along the corridor from the Euphrates via Syria and

Cyprus to Etruria. It can even be shown that both the Assyrian and

the Etruscan models diverge from nature in a similar way; that is,

they are derived not directly from observation but from common

traditional lore. Models of livers are the concrete archaeological

evidence for the diffusion of Mesopotamian hepatoscopy. Besides

Mesopotamia such models have been found since the Bronze Age with

the Hittites of Asia Minor; in Alalah, Tell el Hajj, and Ugarit in

Syria; in Hazor and Megiddo in Palestine; and also on Cyprus.

Assyrian hepatoscopy was practiced at Tarsus in Cilicia in the time

of the Assyrians.

(Left) Etruscan bronze liver found at Piacenza.

(Right) Babylonian 19th Cent. B.C. clay liver (British Museum)

(More about Divination)

Article:

(Sept, 2012) NewsDiscovery.com:

'First Ever

Etruscan Pyramids Found in Italy'.

(Quick-link)

Archaeologists have started clearing an underground

pyramid-shaped vault, the top part of which has been used as a

wine cellar in recent times. As they cleared away the top part,

a series of tunnels, again of Etruscan construction, ran

underneath the wine cellar hinting to the possibility of deeper

undiscovered structures below. Beneath the cellar floor, they

found 6th and 5th century B.C. Etruscan pottery with

inscriptions as well as various objects that dated to before

1000 B.C. Digging through this layer, the archaeologists found 5

feet of gray sterile fill, which was intentionally deposited

from a hole in the top of the structure.

"Below that

material there was a brown layer that we are

currently excavating. Intriguingly, the

stone carved stairs run down the wall as we

continue digging. We still don't know where

they are going to take us," The material

from the deepest level reached so far (the

archaeologists have pushed down about 10

feet) dates to around the middle of the

fifth century B.C. "At this level we found a

tunnel running to another pyramidal

structure and dating from before the 5th

century B.C. which adds to the mystery,"

'The lead archaeologists are

still perplexed as to the

function of the structure

though it is clearly not a

cistern. Dr. Bizzarri notes

that there is nothing like

these structures on record

anywhere in Italy or the

Etruscan world. Dr. George,

notes that it could be part

of a sanctuary, and calls

attention to the pyramid

structures that were

described in the literary

sources as being part of

Lars Porsena�s tomb [1].

Lars Porsena was an Etruscan

king who ruled Chiusi and

Orvieto at the end of the

6th century. Dr. Bizzarri is

however cautious that even

this parallel is not exactly

what is beginning to appear

here, but it does open up

intriguing possibilities.

Both agree that the answer

waits at the base level

which could be 4, 5 or more

metres below the layer they

have now reached'.

(Other

Underground Structures)

(Prehistoric

Italy Homepage)

(A-Z

Pages)

|