|

Location:

Punjab, Indus River tributary, N.E. Pakistan. |

Grid Reference:

30.633 N, 72.867 E |

Harrapa:

(Indus Valley City).

Harrapa:

(Indus Valley City).

The earliest levels

of Harappan culture are at 3,300 BC with the city being established

at c. 2,600 B.C.

The site contains the ruins of a

Bronze Age fortified city, which was part of the Indus Valley

Civilization, centred in Sindh and the Punjab.

(1)

The city is believed to have had as many as 23,500 residents at its

height.

(Map

of Harrapa)

(Map of Indus Valley)

The

Indus Valley Civilization (also known as Harappan culture) has

its earliest roots in cultures such as that of

Mehrgarh, approximately 6,000 BC. The two greatest cities,

Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, emerged

Later c. 2,600 BC along the

Indus River valley in

Punjab and Sindh. (3) The

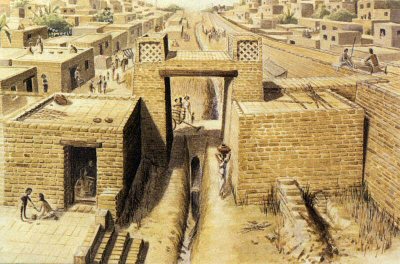

architecture and city planning of Harappa was similar to that of

Mohenjo-daro and the varieties of artifacts recovered from the

excavations confirmed that these two sites represented the same

cultural tradition which has come to be known as the Harappa

Phase of the Indus Valley Civilization.

(2)

They both planned the patterns of

their cities, laying out streets in rectangular patterns and

including drainage systems that led to brick-lined sewers. They

lived in brick buildings, some two and three stories high. In

almost every respect, they were an advanced people.

Chronology:

The

first extensive excavations at Harappa were started by Rai

Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni in 1920. His work and contemporaneous

excavations at Mohenjo-daro first brought to the world's

attention the existence of the forgotten Indus Valley

civilization as the earliest urban culture in the Indian

subcontinent.

The

Harappa site was first briefly excavated by Sir Alexander

Cunningham in 1872-73, two decades after brick robbers

carried off the visible remains of the city. He found an

Indus seal of unknown origin. His work was followed later in the

decade by that of Madho Sarup Vats, also of the

Archaeological Survery of India. M.S. Vats first excavated

the "Granary," and published the results of his and Sahni's

excavations in 1940. Excavations by other archaeologists

continued in the 1930's, and in 1946 Sir Mortimer Wheeler

excavated the so-called fortification walls and found the

first pre-Indus Valley civilization (Kot Dijian) deposits.

Article:

Nov, 2012 (GlobalPost.com):

'Archaeologists Confirm Indian Civillisation is 2000 Years Older

than Previously suspected'

'Indian

archaeologists now believe the ancient Indian civilisation

at Harrapa dates back as far as 7,500 BC. �When Bhirrana

[Rajasthan] was excavated, from 2003 to 2006, Recovered

artefacts provided 19 radiometric dates,� said Dikshit, who

was until recently joint director general of the

Archaeological Society of India. �Out of these 19 dates, six

dates are from the early levels, and the time bracket is

forming from 7500 BC to 6200 BC.�

(Link

to Full Article)

Excavations by

the Harappa Archaeological Research Project have been able to build

on these earlier studies to define at least five major periods of

development starting at c. 3,300 Bc and lasting until c. 1,300 BC

(2). They are

defined in the following fashion:

3,300 BC -

'Ravi' Phase-

The earliest

architectural structures at this time appear to have been huts

oriented north-south and east-west made of wooden posts with walls

of plastered reeds. Some mud-brick fragments of what may be a kiln

have been found, but no complete mud-brick architecture has been

found to date.

Pottery: The

potters wheel became used towards the end of this phase. The use of

pre-firing "potter's marks" and post-firing "graffiti" on pottery

also indicates that concepts of graphic expression using abstract

symbols were emerging. Many of the marks and signs

consisted of a single character or symbol, but one example has three

linked trident or plant shapes. Many of marks and signs used during

the Ravi Phase continued to be employed through the Kot Diji Phase,

and on into the Harappa Phase, where some of them can be identified

as elements of the Indus writing system.

2,800 BC - 'Kot

Diji' Phase -

The wide variety

of raw materials used in specialized crafts during the Kot Diji

Phase indicates the continued expansion of trade networks that were

initiated during the Ravi Phase. Marine shells were brought from

more than 860 kilometers away for ornament manufacture. Various

rocks and minerals were imported over distances of 300 to 1000

kilometers for the production of utilitarian objects such as

grinding stones and chipped stone tools as well for the manufacture

of ornaments such as beads and inlay

Of particular importance at this

time is the first appearance of the Early Indus script that has been

found on pottery, a sealing of a square seal with possible Early

Indus script, and a cubical limestone weight that conforms to the

later Harappan weight category. In 2000 a fragment of an unfinished

square steatite seal carved with an elephant motif was discovered

which indicates that this unique type of seal was being made in

addition to the more common geometric button seals (Meadow, Kenoyer and Wright 2000). These discoveries suggest that

the development of the Indus script, the use of inscribed seals and

the standardization of weights occurred during the Kot Diji period,

some 200 years earlier than previously thought. The emergence of

writing, seals and standardized weights also implies the development

of more complex social and political organizations that would have

required these sophisticated tools and techniques of communication

and administration.

(Full

List of Indus Valley Symbols)

2,600 BC 'Harrapan'

Phase -

The overall size

of the city at this time was over 150 hectares.

This phase is

marked by the greatest variation and widespread use of such seals

appears to be during Period 3B. Small rectangular inscribed tablets

made from steatite begin to appear at the beginning of Period 3B and

by the end of 3B there is a wide variety of tiny tablets in many

different shapes and materials. They were made of fired steatite or

of moulded terracotta or faience. Some of the steatite tablets were

decorated with red pigment and the faience tablets were covered with

a thick blue-green glaze.

The

Harappans used the same size bricks and standardized weights

as were used in other Indus cities hundreds of kilometres

away, such as

Mohenjo Daro .

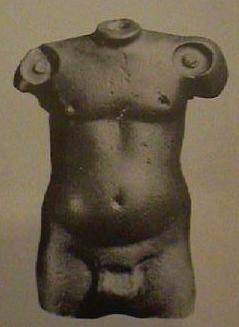

Both male and female torso's were carved, c.2000 BC. Red sandstone, 3

3/4" high (Right).

The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage that were developed and

used in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than

any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more

efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today. The

advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive

dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls.

These giant ring-stones are similar to ones found in

Mohenjo-daro and Dholavira. Local legend claims they were the rings of a

giant 17th century saint (Baba Nur Shah) who is buried on Mound AB.

Early excavators believed that were significant to the ancient Indus

religion. Today, archaeologists think that they were used to secure

wooden posts at gateways to the city.

Several gold

Bars with inscriptions on were discovered at Harrapa.

Some Examples of the numerous seals

discovered at Harrapa.

These various

forms of inscribed tablets continued on into Period 3C where we

also find evidence for copper tablets all bearing the same

raised inscription. The copper tablets at Mohenjo-daro are

incised and have several variations in terms of animal motifs on

one side and inscriptions on the opposite side.

(Mohenjo Daro)

(Indus Valley

Civilisation)

(Prehistoric India)

|