|

Location: Tres Zapotes,

Veracruz, Mexico. |

Grid Reference:

18� 28' N, 95� 26' W. |

Tres Zapotes:

(Olmec Capital).

Tres Zapotes:

(Olmec Capital).

Located on the

slopes of the Tuxtla mountains, this is one of the most important

Olmec cities, and the first to be written about in 1868, along with

the first reports of colossal heads. Tres Zapotes is sometimes

referred to as the third Olmec Capital, as it followed on the demise

of both La Venta and San Lorenzo.

Of particular

interest to archaeology is that the site was continuously inhabited

for over 2000 years (1)

(Layout

of Site)

|

Tres Zapotes (Three Sapodillas). |

Founded c. 1500 BC, it is believed that Tres Zapotes

achieved prominence during the Early Formative

period, between 1200 and 900 BC. During the Late

Formative, 400 BC to 100 AD, when other Olmec

centres such as La Venta were already in decline,

Tres Zapotes sculptures showed the influence of

other artistic styles, such as that of Izapa in the

Guatemalan Highlands, and other regional styles

(2).

This indicates ongoing trade connections with

other cultures, which would have influenced Tres Zapotes.

Despite the fact that the Olmec culture may have no

longer existed as such, Tres Zapotes continued to be

occupied until well into the Early Postclassic

(1000-1200 AD).

There have been several important discoveries at

Tres Zapotes, not least of all, the first discovery

of a monumental Stone head, which have since

inspired much debate over the origin and influence

of Olmec cultural connections.

The Stone Heads

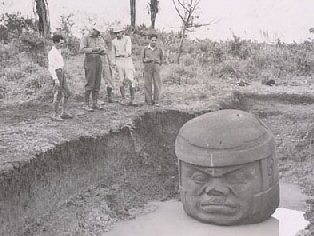

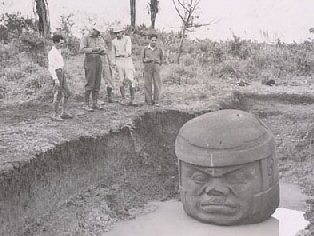

It was

near Tres Zapotes that the first colossal head was

discovered in 1862 by Jos� Melgar. To date, only two

'monumental' heads have

been found locally, labelled "Monument A" and

Monument Q". Smaller than the colossal heads at

San Lorenzo, they measure slightly less than

1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) high. Together with the cruder

and significantly larger head at Rancho la Cobata,

these colossal heads show evidence of a specific style

of dress and sculpture, differing from that of San

Lorenzo and La Venta.

Scarcely 10 km (6 mi) to the east stands Cerro el Vig�a, an

extinct volcano and important source of basalt and other volcanic stone, sandstone, and clay.

The nearby small site of Rancho la Cobata, on the northern flank

of Cerro El Vig�a, may have functioned as a monument workshop �

most of the basalt stonework at Tres Zapotes was crafted from

the colossal, "spheroid", smooth-faced boulders found even today

at the summit of Cerro El Vig�a. Some of these boulders are more

than 3 meters in diameter.

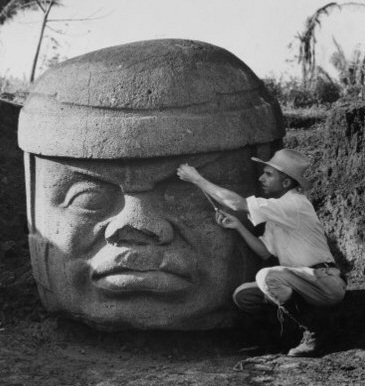

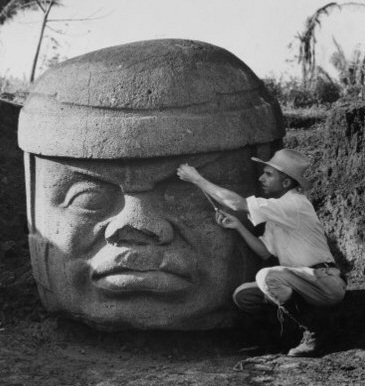

Monument A: Height 1.47m (4.82 ft). Carved from a block of

Basalt. Current location, Community museum, Veracruz. Monument Found

near the Calendar stone (Stela C), Stirling (seen kneeling beside

it) had this to say of it:

"...The head was

a head only, carved from a single massive block of basalt, and

it rested on a prepared foundation of un-worked slabs of stone

... Cleared of the surrounding earth it presented an

awe-inspiring spectacle. Despite its great size the workmanship

is delicate and sure, the proportions perfect. Unique in

character among aboriginal American sculptures, it is remarkable

for its realistic treatment. The features are bold and amazingly

Negroid in character..." (3)

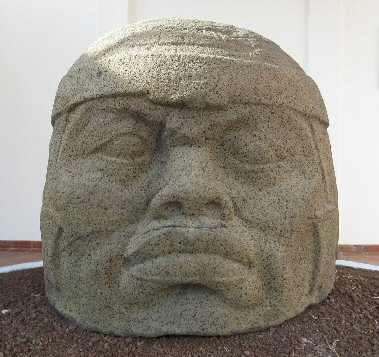

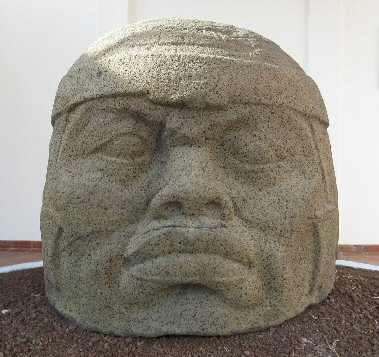

Monument Q -

Height 1.47m (4.82 ft). Carved from a distinctive porphyritic basalt and

weighing over eight tons, this was the second colossal

head to be discovered at Tres Zapotes. Current location

Santiago Tuxtla Museum, Veracruz.

Image (Right): The rear of Monument Q showing

Ethiopian style braided hair. This monument in particular offers one of the strongest arguments

in favour of the heads representing people of African origin.

It is interesting that the two colossal heads

found at Tres Zapotes, monument A and monument

Q, were not found in the core zone of the site,

but rather in the residential periphery, in

Group 1 and Nestepe Group.

(Old World - New World contact in

Pre-Columbian America)

(Images

of All the Mexican Stone-Heads)

The

Olmec Long-Count:

In Addition to the

stone heads, Tres Zapotes excavations revealed

the earliest example of a dated 'Long Count'

inscription from 'Stela C', in the year of 31 BC.

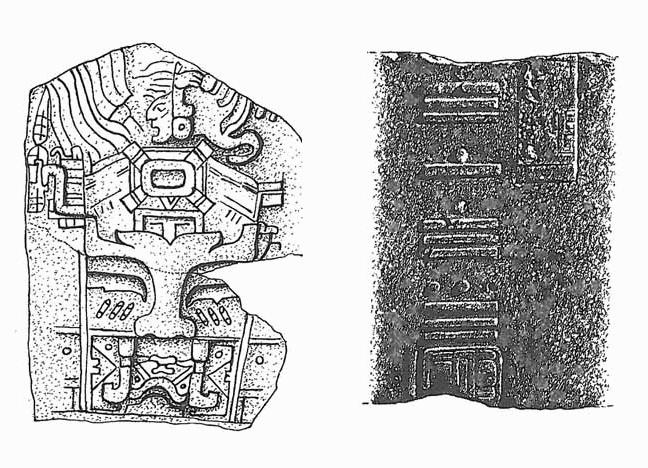

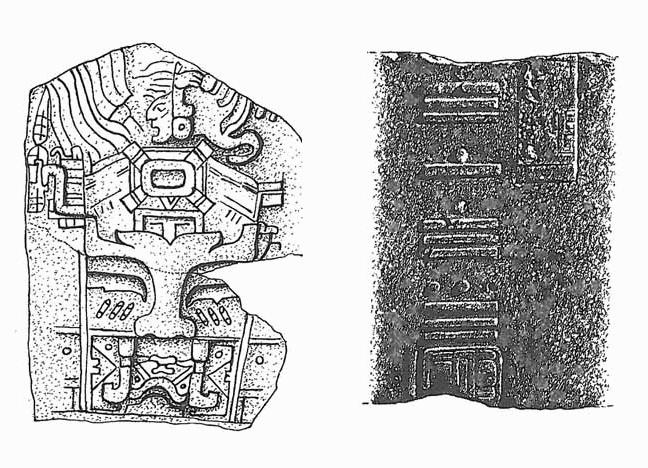

Tres Zapotes Stela C: Tres Zapotes is

famous for Stela C, a rectangular stone block

with a post-Olmec Izapa-style mask on one side,

and a Long Count date expressed in bars and dots

on the other (below). The date, 7.16.6.16.18

6 Eznab (31 B.C.), was at the time, the Mesoamerica's

oldest 'Mayan' Long Count inscriptions. What was shocking

about this was that Tres Zapotes was not a Maya

site�not in any way at all. It was entirely,

exclusively, unambiguously Olmec. This

suggested that the Olmecs, not the Maya, must

have been the inventors of the calendar, and

that the Olmecs, not the Maya, ought to be

recognized as �the mother culture� of Central

America.

Illustration of

Stela C: Front and Back, showing the date 31 BC.

This very important

fact has revealed several interesting aspects of

Olmec culture. The Olmecs

were much, much older than the Maya. They�d been

a smart, civilized, technologically advanced

people and indeed, it appears that it was they,

and not the Maya, who

invented the bar-and-dot system of calendrical

notation, including the enigmatic starting date of 13

August 3114 BC.

In addition,

and of equal importance, a nearby stela has

produced the longest glyph text in Meso-America,

leading to a question over the origin of writing.

|

Tres Zapotes: Gallery of

Images.

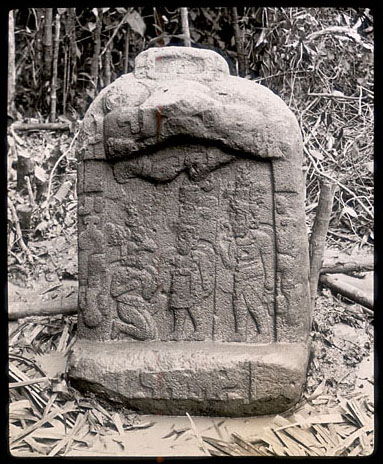

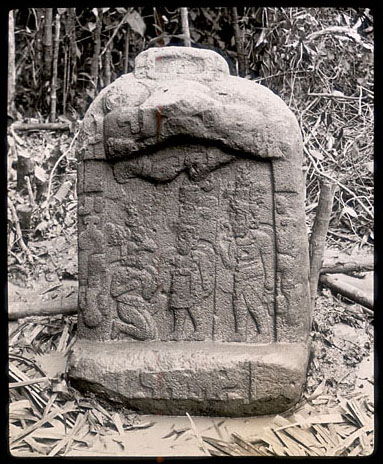

Tres Zapotes Stela D:

This monument

shows the open mouth of an animal, possibly

representing the Earth Monster. Three human

figures are carved in low relief in the back of

the mouth. In 1939 Stirling described the style

of this stela as �quite suggestive of Mayan

art.� This was, however, before the style was

recognized as preceding the Maya and before the

name Olmec was applied to the style and to the

civilization that produced it.

This

single Stela took 20 men to remove it from the

ground. It has been compared to the Izapa Stela, and

is tentatively dated to c. 600 - 100 BC

(4).

'One of the major

differences between the ancient civilizations of Eurasia and those

of the Americas was the absence of wheeled transportation in the

latter...'

Soon afterwards the American

archaeologist made a second unsettling discovery at Tres Zapotes was

also the place where archaeologists unearthed the first example of a

Pre-Columbian wheeled object. Since then several more have been

found in both Olmec and Mayan locations dispelling the myth that the

wheel was unknown before the conquest.

(Other

Examples of the Wheel in Pre-Columbian America)

Bearded Olmecs.?

This particularly

significant discovery is of the head of a man, with pointed beard,

earplugs and headdress, from one of the mounds near Tres Zapotes.

Neither the beard

of the moustache are found in the Amerindian genotype.

There are several

other bearded figures in Olmec art, again placing an emphasis on the

idea that the Olmecs were a multi-cultural society with influences

from different cultures from the both Pacific and Atlantic..

(Photo Credits:

Smithsonian Olmec Legacy)

(Olmecs

Homepage)

(La

Venta) (San

Lorenzo)

(The

Olmec Stone Heads)

(Mexico

Homepage)

(Pre-Columbian

Americas) |