|

Location:

Tyrrhenian Sea, Mediterranean. |

Grid Reference:

Approx centre: 40� N, 9� E. |

Sardinia:

(Sardegna)

Sardinia:

(Sardegna)

Sardinia is

currently an autonomous region of Italy and the second largest

island in the Mediterranean after Sicily. Although there is

evidence of human occupation from the Palaeolithic, the island

was only permanently settled from around 6,000 BC in the early

Neolithic,

(1)

probably from Corsica, or the

continent via Corsica.

There are

several distinct forms of Sardinian monuments that dominate

the prehistoric landscape: The Nuraghi, Domus de Janas and the Tombes Gigantes.

(Relief

Map of Sardinia)

|

Tombe di Giganti 'Giant's Tombs': |

The Tombs

of Giants, so called because of their gigantic dimensions, are

another typical element of Sardinia's megalithic period. Usually

the frontal part of their structure is delimited by some sort of

semicircle (exedra), almost as to symbolize a bull's horns (Many

Tombs of Giants are also oriented towards the Taurus'

constellation, precisely towards the brightest star, Aldebaran

(Alpha Tauri). This is the case of the Tombs of �S'Ena e Tomes�

in Dorgali, �Goronna� in Paulilatino and �Baddu Pirastru� in Thiesi (5).

Viewed from above the shape of the Tombs of Giants has also been

said to mind that of an uterus or a woman in labour.

(View

overhead plan)

This interpretation

confirms how closely connected life and death were for nuraghic people and how their

structures were linked to the cult

of fecundation.

The Tombs of Giants are scattered throughout the island. So far about 320

have been found, but it is thought that Sardinia may

still be hiding many more of them.

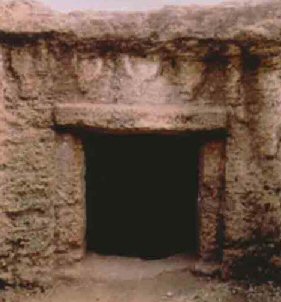

Tomba di Dorgali,

showing closely carved stones at the entrance and a small portal at

the bottom which was carved with what is interpreted as a

representation of a 'false door leading into the other world of the

dead'.

(left) Coddu

Veccio, and (right) Li Goghi, two of the largest Tombs on

Sardinia.

The

Giants Tomb of Olbia (1500

to 1100 BC). The

central stone has been removed revealing

the main structure which lies behind it,

which can only be described as an Al�e Couverte.

The monuments are the result of at least

two stages of development; the first

being the construction of an internal

megalithic burial chamber, and the

second being the external forecourt,

believed to be for congregations, a

similar design as seen in front of the

temples on Malta.

|

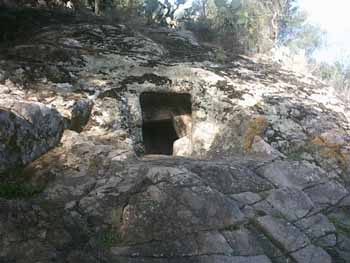

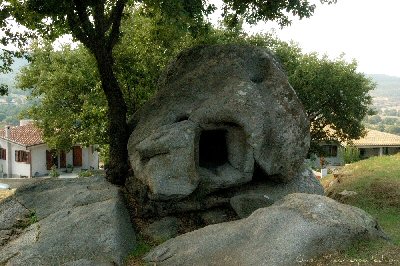

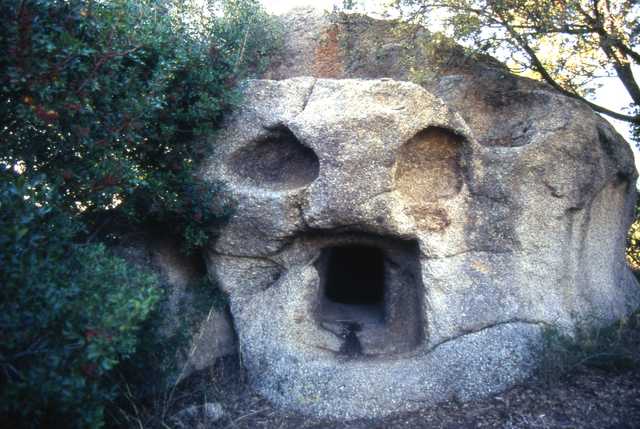

Domus de Janas: 'Spirit Houses' or 'Faerie houses'. |

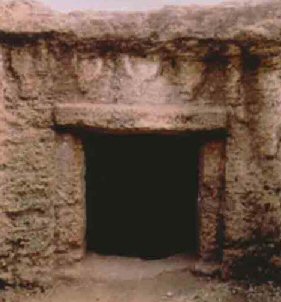

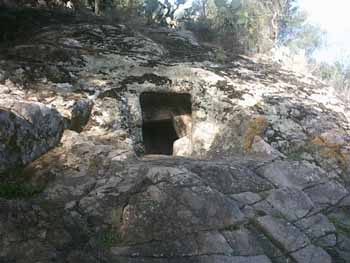

Especially interesting are the tombs known

as domus de janas

(Spirit homes). They

were built by hollowing out large rocks to

form a funeral chamber within, leaving the

natural rock surface to serve as the outer wall.

This one above is on the site of the

S'Ortale e Su Monte/San Salvatore

complex near

Tortol� on the south-eastern coast of the island.

Two

more examples of the aptly named 'Fairy houses'.

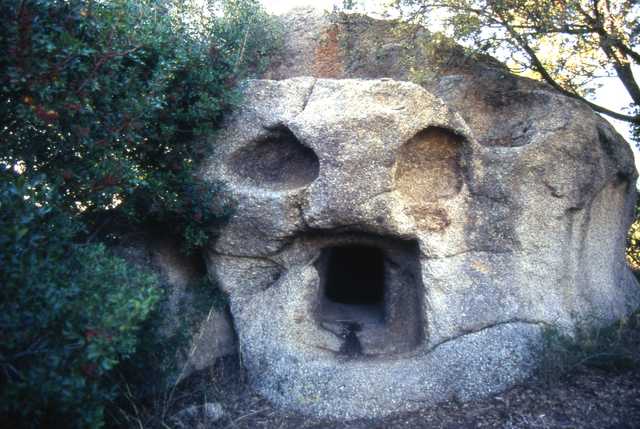

The

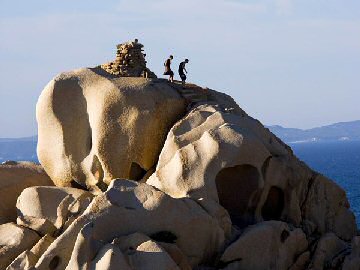

Roccia dell' Elefante:

This

natural trachyte monolith near Castelsardo has long held an

emblematic presence in the region as there are several

pre-nuraghic domus de Janus carved within its structure.

It is

believed to have long been a significant site as it is located

next to the monument known as 'Multeddu', within which

was found an inscription reminiscent of a temple dedicated to

the Goddess Isis, and a statuette to the goddess Ceres (Now in

the Museo Sanna in Sassari). The chambers are carved with

doorways, with relief frames similar to the chambers of Anghelu

Ruju (below), along with two large curling bull-horns in one of

the chambers.

It is

of course interesting to note that the similarity to an elephant was

presumably recognised over 5,000 years ago, suggesting that the

people who carved it and built the Multeddu next to it must have

already known what an elephant looked like and were therefore

likely to have been regular travellers around the Mediterranean

(i.e. having already been to Africa).

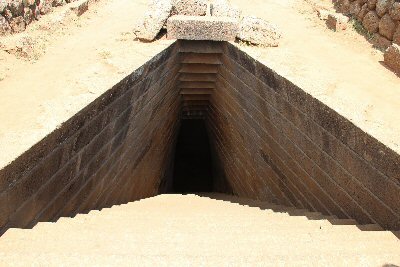

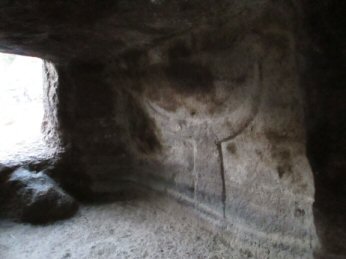

Necropole di Anghelu

Ruju:

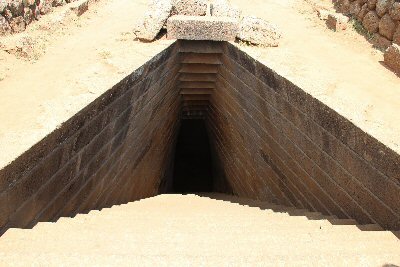

The Necropole di Anghelu

Ruju is the largest ancient burial ground on Sardinia and dates from

3,500-1,800 BC. The Necropole di Anghelu

Ruju is the largest ancient burial ground on Sardinia and dates from

3,500-1,800 BC.

The thirty-six

tombs are cut from or made of sandstone, sharing some common design

features: a series of steps down from the entrance and a descending

passage to a large burial chamber with smaller connecting chambers.

Many of the 36 tombs have doorways carved to simulate trilithons. (A

feature with stark similarities to those seen in the

Hypogeum, on Malta).

Many of the doorways are carved to imitate smoothly

dressed trilithons, but what makes Anghelu Ruju famous are the

carvings of long-horned bulls' heads in and around three of the

tombs (numbered 19, 20 and 30). These symbols were sometimes painted

in red ochre, and they have been interpreted in different ways. It

is worth noting that many of the human bones found in the tombs were

lying under a sheet of white shells; this could indicate that most

of the ancient Sardinians buried here were fishermen.

Among the many grave goods dating from 2200 to 1700 BC found at

Anghelu Ruju, there are obsidian, barbed and flint arrowheads, an

axe and an awl from Ireland, a copper ring from East Europe,

copper daggers from Spain, Beaker pottery, small

marble statuettes, and spiral wire beads. Something which attests to

the strong and extensive trading in operation at that time.

Carved Portals at (Left) Tomba di Santu Pedru, (Right) Anghelu

Ruju.

From about 1,500 BC onwards, villages were built

around the round tower-fortresses called nuraghi (Northern Sardinian

nuraghes,

Southern Sardinian nuraxis, plurals of nuraghe and

nuraxi respectively),

which were often reinforced and enlarged with

battlements. The boundaries of tribal territories

were guarded by smaller lookout nuraghi

erected on strategic hills commanding a view of

other territories. Today some 8,000 - 10,000 nuraghi dot the

Sardinian landscape

(4). According to some scholars the nuragic peoples are identifiable with the

Shardana, a tribe of the "Sea

Peoples" (2) From about 1,500 BC onwards, villages were built

around the round tower-fortresses called nuraghi (Northern Sardinian

nuraghes,

Southern Sardinian nuraxis, plurals of nuraghe and

nuraxi respectively),

which were often reinforced and enlarged with

battlements. The boundaries of tribal territories

were guarded by smaller lookout nuraghi

erected on strategic hills commanding a view of

other territories. Today some 8,000 - 10,000 nuraghi dot the

Sardinian landscape

(4). According to some scholars the nuragic peoples are identifiable with the

Shardana, a tribe of the "Sea

Peoples" (2)

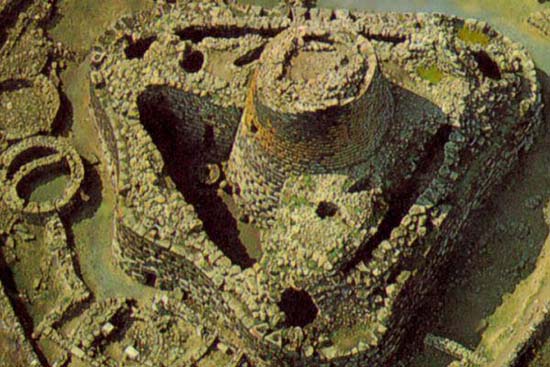

They had various rooms and

floors, corridors, cells, internal staircases, even

parapets, for they were true miniature castles,

built to dominate the surrounding countryside.

Architecturally, there are similarities to

structures of the ancient

Mycenaean civilization on

Crete, such as the 'Tholos' - beehive shaped

internal chambers, leading some scholars to believe that these

original Sardinian stonemasons came from that part

of the Mediterranean. The remains of dozens of these

nuraghi are still found throughout the

island, primarily in the north.

(Photo

Credits: Ivo Piras)

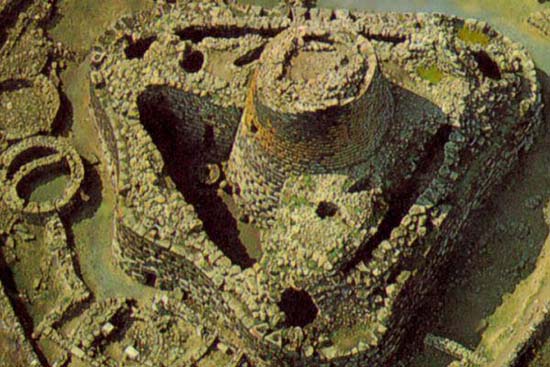

The nuraghi at Barumini is the

largest on Sardinia and is located in the

southern part of the island roughly between Oristano

and Caglieri. When it was first rediscovered it was

covered in soil and mistaken for a hill.

To

breach the Nuraghe of Barumini, enemies had to reach a small entrance

located about 7 meters high, making "Su Nuraxi"

in the eyes of the enemy an impenetrable fortress.

Even today, after the excavations carried out by the

archaeologist

Giovanni Lilliu in the 50s, the only entrance

to the fortress is the "sky door". Lilliu's

archaeological excavations proved that Su Nuraxi was

being inhabited until the third century AD.

(3)

(Map

of the Nuraghi on Sardinia)

The Function of the Nuraghi:

There is

no absolute consensus on the function of the

nuraghi: speculation ranges from religious

temples, ordinary dwellings, rulers'

residences, military strongholds,

meeting halls, or a combination of the

former. Some of the nuraghes are,

however, located in strategic locations

� such as hills � from which important

passages could be easily controlled.

They might have been something between a

"status symbol" and a "passive defence"

building, meant to be a deterrent for

possible enemies. It has been noticed

that they are often inter-visible, and

where they are not, smaller intermediate

versions were built, suggesting

continuity for signalling.

Examples of early or 'simplified' Nuraghi.

Small-scale models of nuraghe have often

been excavated at religious sites (e.g.

in the "maze" temple at the Su Romanzesu

site near Bitti in central Sardinia). Nuraghi

were often located next to temples,

specifically water temples. (This theme

is expanded on below).

The work

of Juan Belmonte and Mauro Zedda has

studied 272 simple and 180 complex

nuraghi; they noted that the orientation

of the door was always turned towards

the south-east, where the sun was known

to rise. Indeed, they argue that several

of the windows in the nuraghi have

solar, lunar and/or stellar alignments.

One such astronomical phenomenon was

observed in the Nuraghe Aiga di

Abbasanta. Here, the summer solstice sun

entered into the construction itself and

creates an impressive solar display.

Such solar alignments argue strongly for

a religious function, if only partial,

as such alignments clearly have no

defensive qualities.

Examples of more

complex Nuraghi.

In the

Bronze age two dramatic events took

place that had their repercussions on

the east and the west Mediterranean,

including Sardinia. The first event was

the decline of the palace culture of the

Minoan period on Crete and the rise of

the Mycenaean's, between 1500 and 1400

BC. The second event was the time of the

incursions of the Sea People in Egypt

and the decline of the Mycenaean palace

culture, around 1200 BC. It was around 1200 BC

that on Sardinia complex nuraghi were

built, an amplification of a central

nuraghe with one or more additional

towers, a small courtyard and even

additional defensive walls and minor

towers. Lilliu has called this period La bella et� dei nuraghi, the climax

of the nuraghe-culture.

Sacred

Wells:

The nuragic well is another important

element of the Sardinian megalithic heritage. At the moment we have

around 40 wells reachable thanks to a monumental staircase after

which there is an atrium (Tholos) for holding the water.

In

the case of the sacred well of

Santa Cristina in Paulilatino-Oristano, it has been

assessed that thanks to the hole situated on the tholos vault, the

moon is reflected on the well. This happens during a predefined

period, that is to say at the utmost declination of the moon, every

18 years and 6 months. Thanks to the staircase, the sun�s light is

reflected in the well during the autumn equinox (between the 22nd

and the 23rd of September) and also during the spring equinox

(between the 20th and the 21st of March).

The moon�s peculiarity has been noticed also in other

wells; also the solar reflection is sometimes visible during the

summer solstice (between the

20th and the 21st of June).

The Santa Christian Sacred well,

exquisitely constructed, and orientated to receive the light from the maximum setting moon on its

18.6 year Lunar cycle.

(Left) Pozzo

Sacro di Predio Canopoli, (Right) Posso Sacro di Sa Testa

(Italy

Homepage)

(Malta)

(A-Z

Pages)

(Index

of Sacred Places)

|

From about 1,500 BC onwards, villages were built

around the round tower-fortresses called nuraghi (Northern Sardinian

nuraghes,

Southern Sardinian nuraxis, plurals of nuraghe and

nuraxi respectively),

which were often reinforced and enlarged with

battlements. The boundaries of tribal territories

were guarded by smaller lookout nuraghi

erected on strategic hills commanding a view of

other territories. Today some 8,000 - 10,000 nuraghi dot the

Sardinian landscape

(4). According to some scholars the nuragic peoples are identifiable with the

Shardana, a tribe of the "Sea

Peoples" (2)

From about 1,500 BC onwards, villages were built

around the round tower-fortresses called nuraghi (Northern Sardinian

nuraghes,

Southern Sardinian nuraxis, plurals of nuraghe and

nuraxi respectively),

which were often reinforced and enlarged with

battlements. The boundaries of tribal territories

were guarded by smaller lookout nuraghi

erected on strategic hills commanding a view of

other territories. Today some 8,000 - 10,000 nuraghi dot the

Sardinian landscape

(4). According to some scholars the nuragic peoples are identifiable with the

Shardana, a tribe of the "Sea

Peoples" (2)